Learning from others’ mistakes is a good teacher for the novice, and many veterans have already learned some of these handloading mistakes the hard way. Commit these few pitfalls to memory to avoid repeating them.

1. Not checking ammo-to-chamber fit

My college roommate, James Pilgrim, learned that hard way about handloaded ammo on the opening day of Mississippi’s deer season in 1981. His maternal grandfather had cooked up a fantastic deer load for his Remington 740 .30-06, and it worked just fine in Uncle Jimmy’s Remington 742. The problem was that James didn’t cycle any of his Gramp’s ’06 loads through his own 742 before we got to the woods that morning. Everything was fine until a fat spike ran up onto the ridge where James was waiting that afternoon. He centered the buck in his crosshairs and got a loud “click” instead of the expected boom. The bullet had enough runout that it hung in the lands just enough to keep the bolt from fully closing. That was the only buck James got a shot at the entire season. Every round that is intended for self-defense, match, or hunting should be run into a case gage, or cycled through the intended weapon in a safe place, to make sure they will all fit your chamber properly and the headspace is correct.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

2. Not handling and seating primers properly

Seat your primers slightly below flush so they have maximum sensitivity. This is even more critical in double-action revolver or pistol. Care must be taken when handling primers, too. It is easy to get case lube or some other unintended substance on primers, which will kill them dead as a hammer. This one cost me a big 10-pointer on the opening day of Tennessee’s deer season in 1981. (My college buddy, James, was hunting with me that morning, just seven days after he had his own malfunction on a buck, and got a big laugh when I told him the story.) Another thing to remember is that primers are volatile by their very nature. When hand priming, always point the cartridge case away from your body when seating primers.

3. Not keeping powder properly labeled

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

It is common to use more than one powder measure, such as one on a progressive press and a couple more set up individually for rifle and pistol. If you have a busy reloading setup, it’s also quite possible to swap back and forth between reloading projects. The problem arises when you have powder and in several different measures and you lose track of which powder is in which measure. The simplest way to keep track is to mark the appropriate powder type on a stick-on label and attach it to the measure.

- RELATED STORY: Shotshell Handloading 101 – It’s Time to Get Loaded

4. Not storing powder properly

Powder can grow stale over time. This can create a hazardous situation, which can result in a dramatic change in burn rate and subsequent pressure spikes when a round is fired. Stale powder gives off a strong odor. If you have a newer can of the same powder, sniff it. Then, smell the old powder. If the older can gives off a strong, distinct odor, dispose of it properly.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Another mistake I learned the hard way was leaving powder in measures for any length of time. What happens is the hygroscopic properties of powder soaks up humidity, which is a bad thing. Once the powder gets damp, it can wreck havoc with the internal parts of a measure, too, by leaving a coat of rust in areas of tight tolerances.

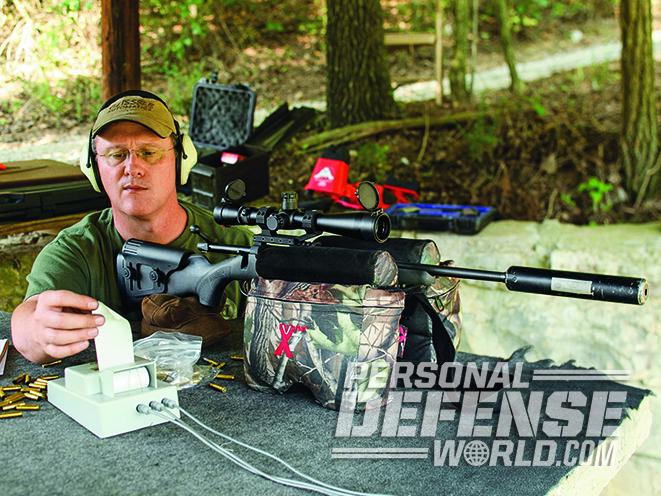

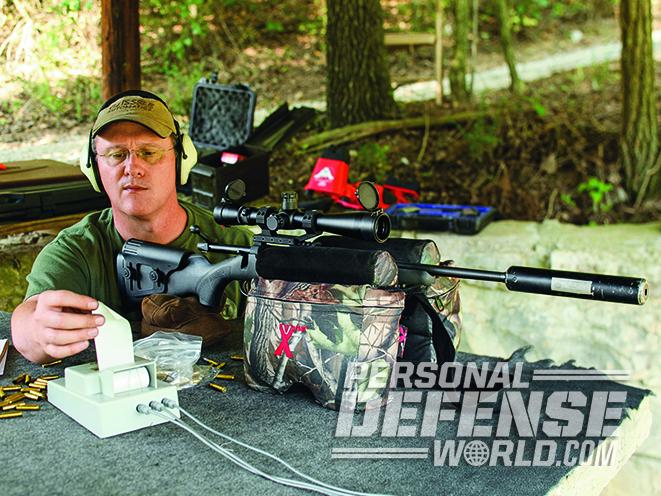

5. Not filling cartridge cases adequately

Detonation is a bad thing, when it comes to firing a round in a rifle or pistol. This situation typically occurs when too small of a powder charge is placed in a large case. Powder is meant to burn at a specified rate, not explode creating a pressure spike in the chamber. What can happen is that a too-small powder charge can shift to the front of a case when the muzzle is pointed down. When the primer ignites the distant powder charge, if at all, it can create a nasty situation. In other situations, some powders don’t behave predictably when too little of it is loaded in a case. Shooting suppressors and subsonic rifle loads is a good way to get into trouble when you start experimenting with reduced powder charges. Experimenting with the wrong powder and barely filling a case can wreck a rifle and injure the shooter and bystanders.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

6. Not keeping water away from molten lead

Experienced bullet casters fear the “tinsel fairy.” Just a drop of water dripping from a sweaty nose into a pot of molten lead will create a splash of lead to leave the pot in a hurry. Water quenching is a good way to get bullets to a higher BHN when they are dropped from the mould, but be careful that no water splashes up and into the pot. Also, be careful about storing lead ingots in damp places or storing them in cold environments and suddenly bringing them inside. I have seen the result of a damp ingot dropped into a half-full pot of molten lead. You can’t move fast enough to get away from an erupting pot of hot lead. Always wear cotton clothing, leather gloves and eye protection when casting.

- RELATED STORY: The 10-Shot Rule For Determining Handload Accuracy

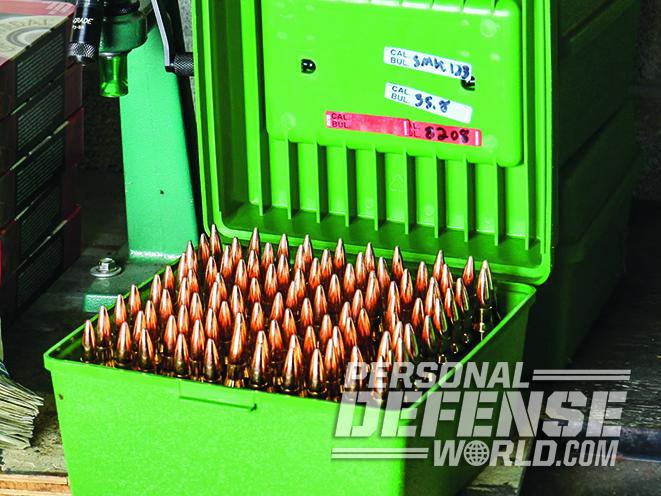

7. Not labeling handloads

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Keep all your handloads clearly labeled as to the powder, charge weight, primer, bullet, and overall cartridge length. Note the intended firearm, too. If you have a chronograph, note the velocity and temperature when the velocity reading was taken. Also, note the firearm that was used including barrel length. Make sure your label will last as long as ammo is stored, too, so use a permanent marker.

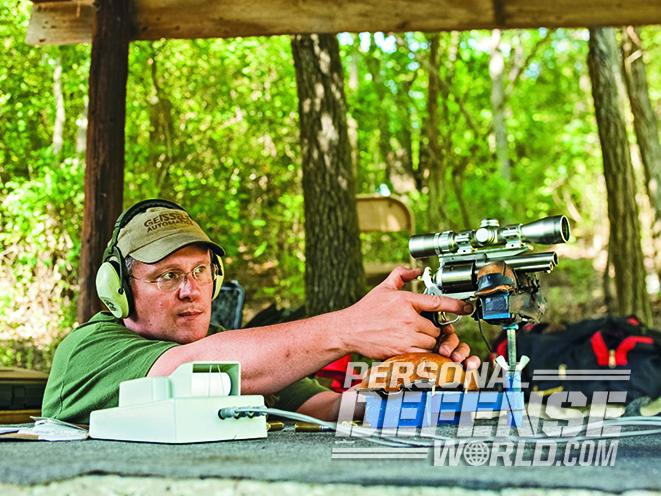

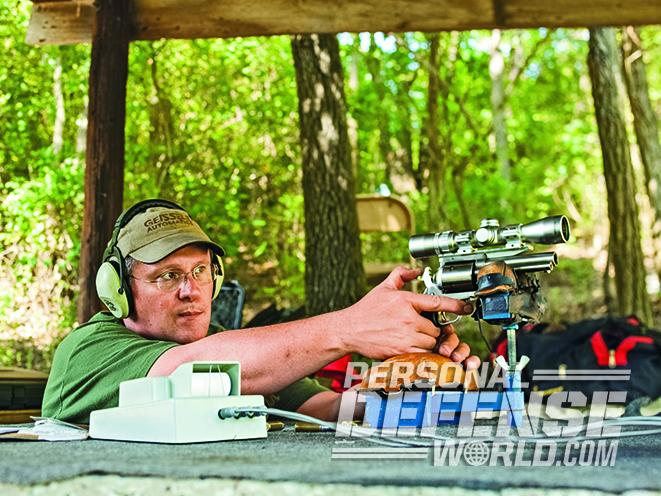

8. Not heavily roll crimping revolver cartridges

Put a heavy roll crimp on your big bore revolver cartridges. If you don’t, the bullet can move forward under recoil and tie your cylinder up so it will not rotate. This is more commonly seen in heavy-recoiling revolvers, but it can bind up something as small as a .32 H&R Magnum. Another benefit of crimping handgun cartridges is consistent bullet release. This will make loads more accurate. Some powders burn more efficiently, too, when they meet the resistance of a strong roll crimp. This translates into more accurate handgun loads.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

9. Not checking the zero on any electronic or balance beam scale before use

Electronic scales come with check weights for a reason. Some scales are more reliable than others, but they need to be checked before every use. Balance beam scales are slow, but more reliable than electronic scales… but they need to be zeroed, nonetheless. All you have to do is move a balance beam scale from one place to another on your bench and you might get into trouble. If the bench is not perfectly level, the scale might not read correctly. I ran into trouble once when I zeroed a beam scale, then moved it where it straddled a seam in the plywood bench top. I wound up pulling 100 bullets after finding the mistake.

- RELATED STORY: 10 Must-Know Reloading Tips for Rookies and Vets Alike

10. Not keeping shell holders clean and crud free

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Over the past 40 years I have learned the hard way that shell holders must be kept clean of any debris. I can’t count the number of cases that have been resized improperly when kernels of powder or other trash got mashed into the recesses of a shell holder. Unwittingly, I rammed case after case up into a resizer on a cant, which created problems. This is just as bad when seating and crimping bullets, too. Funny, but handloaded cartridges seem to shoot better when cases and bullets start off straight. Case lube, and even bullet lube, can work its way into a shell holder, which will attract every piece of dirt it can over time.

Hopefully, some of these lessons learned the hard way will keep you on the right path when handloading.

This article was originally published in ‘The Complete Book of Reloading’ 2017. For information on how to subscribe, please email subscriptions@

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below