The performance of any handloaded cartridge can only be as good as the component parts that go into the making of it. Obviously, a great deal of thought must be given to the selection of the best potential powder, the primer to be used and, of course, the style of bullet that best matches whatever shooting venue you will be embarking on. Unfortunately, however, I sometimes get the feeling that all too little attention is given to the component that is saddled with the responsibility for holding all of these parts together—the cartridge case.

When a shooter attempts to stretch out the life expectancy of their brass or use cases that may have a questionable history behind them, it strikes me kind of like traveling with an old, worn-out suitcase. Sure, you can certainly do that, but regrettable circumstances may be in the making.

Good Deals?

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I’m certainly not opposed to taking advantage of a bargain when I find one, but when it comes to rifle cartridge cases, caution should factor into your decision. A valuable aid for shooters comes from the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI), which is saddled with the responsibility of ensuring that some consistency in manufacturing and design takes place within the shooting products industries. SAAMI was initially established in 1926 in association with the nation’s leading manufacturers of firearms, ammunition and components and under the auspices of the federal government. Part of that organization’s responsibilities is setting the standards for such things as ammunition cartridge cases. Within those requirements are standards for safety, interchangeability, reliability and quality, but manufacturers still retain some design flexibility. For example, it is fairly common to find slight variations in the internal dimensions and design of cartridge cases, which can have an effect on the powder capacity of those cases and their shooting performance.

Case Variations

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

If you had a way to slice a variety of cartridge cases down the middle, in some instances you would likely notice differences in their internal construction, even when the calibers are the same and, sometimes, even when they were made by the same manufacturer. While at first glance those variations might seem minor, even slight deviations in these areas can manifest themselves into important differences in performance. The most common areas affected: the shape of the internal base and dissimilarity in the thickness and consistency of the metal used and occasionally even in the actual composition of the metal. Possibly the most common metal used for cartridge case manufacturing is comprised of a mixture of 70-percent copper and 30-percent zinc, but Norma, for example, typically uses a softer metal mixture of 72-percent copper and 28-percent zinc. In this case, Norma favors this softer composition because it makes forming the cases a little easier at the factory.

RELATED STORY: RCBS Precision Mics – Measuring Headspace & OALs

To get a rudimentary understanding of how much variation in metal thickness might be expected, I recently decided to use a micrometer to measure the case mouth thickness of a variety of once-fired and unfired brass. The cases I selected were from a collection of both American and foreign manufacturers and included three different centerfire calibers (.308 Winchester, .375 H&H and .300 Winchester Magnum). In a few instances, I found the case neck thicknesses measured exactly the same, but others varied sometimes by as much as 0.00035 inches. Again, these differences may seem minor at first glance, but they will have an effect on the powder capacity of the cases and how tightly the bullets are held in place. They may cause variations in the generated pressures and thereby affect your shooting accuracy and consistency.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Nickel-plated cases have become quite popular in recent years, largely because the plating resists tarnishing. But even though that plating layer is microscopically thin, it still adds to the thickness of the case material on both the outside and the inside of the cases, which in turn will again have a bearing on the powder capacity of those cases.

In order to get an idea of how much influence those common variations would have on the powder capacities, I decided to fill a variety of different cases with powder and then compare the weights of those charges. My study group consisted of three different manufacturers for each of four calibers (.243 Winchester, .308 Winchester, 7mm Remington Magnum and .300 Winchester Magnum). In all instances, the cases were either new or once-fired. I filled each case to the top with Hodgdon Varget powder, tapped the side to settle the charge, then raked the top off even and weighed the charges. Percentage-wise, the 7mm Remington Magnum cases that I tested varied the least at about 2.3 percent, and the .243 Winchester came in with the greatest amount of spread at 4.6 percent. The chart shows the results in more detail.

Military Brass

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

When I talk about “military brass,” I’m not talking about those guys who sometimes used to harass me while I served in the military, but rather the cartridge cases that were produced specifically for use by our armed forces. In this case, that brass frequently contains primers that have been crimped in place. While under the rigors of military life, this likely discourages the tendency for those primers to work free, but it also presents a burden for those of us who attempt to reload those cases. Recently, I purchased a fairly large batch of factory-loaded 5.56mm ammo that I mistakenly thought had been loaded for civilian use. I found out differently only after resizing the first piece of brass and found the new primer wouldn’t seat. Immediately it dawned on me that I’d gotten my hands on some cartridges intended for military use. The result was that I had to dig out my primer pocket swage tool in order to eliminate the problem before I could seat even one new primer.

RELATED STORY: How To Recycle Range Brass

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

There are basically two swage tool designs available on the market. The most common of those is the bench-mounted system, which typically bolts to the top of your reloading bench. RCBS makes another tool that it calls the Primer Pocket Swager Combo 2 that accomplishes the same objective of removing the military crimp, but instead of bolting to the bench, it screws into the top of the reloading press, much like your dies do. I haven’t personally used this style of swage tool, but the theory seems to be a good one, and with a manufacturer’s suggested retail price of $42.45, it is less than half of what most bench-mounted models generally cost. The good news here is that, with the proper tools, it isn’t very difficult to take the crimps out, and once removed, you don’t ever have to do it again, unless of course you run afoul of some more of the military stuff.

Cracks, Slits & More

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Growing up in a poor family, we all had to scrimp and save wherever we could, and because of that I still sometimes use things until they literally fall apart. But while that might make good sense when it comes to an old pair of work boots, it certainly isn’t a good idea for rifle cartridge cases. All the stretching and reforming that the brass undergoes in the firing and reloading processes can stress the metal beyond its limits. Cracks and splits generally start to form from the inside of the brass and may go undetected until they burst through to the outside.

RELATED STORY: 7 Reloading Accessories For Creating Accurate, Reliable Ammo

For this reason, I like to keep track of how many times each piece of rifle brass has been loaded and then discard it long before a problem has a chance to develop. I sometimes place a hash mark on the heads of the brass each time I load it, which provides an easy reference as to its history. Sometimes, however, cracks can occur after only a few loadings, and to help further ensure I don’t experience a problem, I use a simple little tool that I make myself to check for beginning cracks. Starting with either a small screwdriver or a piece of heavy-gauge wire, you should grind the tip off to a sharp point and then bend it at a right angle. Once formed, it must be capable of being inserted directly inside the cartridge case so the point can be rubbed up and down near the base. Doing so allows you to feel the resistance produced by the crack, and when that happens the brass should be immediately tossed.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Prepping Cases

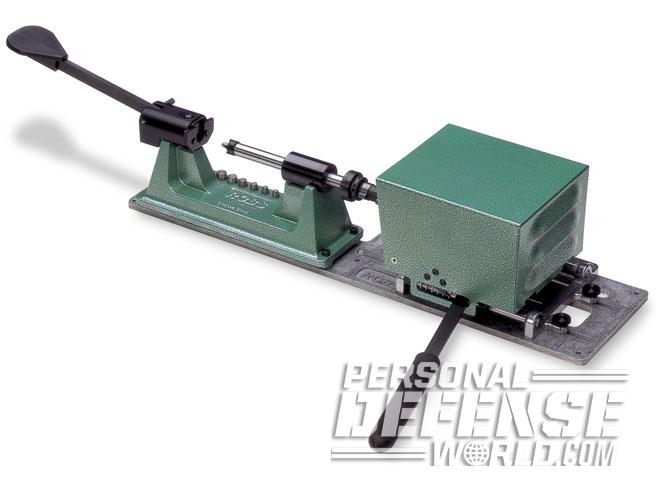

Long before you can seat a primer and drop in the powder charge, there will be a considerable amount of case prep work necessary. Some of those procedures can be a bit time consuming and cumbersome to accomplish, but there are some great new tools available to make those jobs less of a burden. One great example is RCBS’ electric Trim Pro 2 case trimmer. For many years I have used a variety of hand-cranked case trimmers and on many occasions worn myself out doing so. On the other hand, the Trim Pro 2 makes those tasks quick and nearly painless. Once the unit has been set to the proper trim length, all you have to do is stick the cartridge case in the shell holder and push down on the handle. The Trim Pro 2 literally takes over from that point on, and within a few seconds your case is perfectly trimmed to the proper length.

Another great tool that has the ability to speed up your reloading is the Lyman Case Prep Xpress. This is an all-inclusive motorized tool that allows you to easily and quickly debur and chamfer the necks of the brass, uniform the flash holes of the primer pockets and even clean and lubricate the case necks. At the top of the unit are five receptors which various tools of your selection may be attached to. Once you have screwed those tools into place and the Case Prep Xpress is turned on, all five stations turn simultaneously, allowing you to move from station to station processing your brass. The tools included with the unit are a VLD (inside neck) deburring tool, an outside deburring tool, large and small primer pocket cleaners, large and small primer pocket reamers, large and small primer pocket uniformers, a brass shavings brush, three case neck lube brushes and a tube of mica dry lube. The versatility inherent in the Lyman Case Prep Xpress will allow you to prep brass ranging from tiny .17-caliber centerfires all the way up to the big-bore .458s in a quick and efficient manner.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Parting Advice

No matter how careful you are to adequately lube your cases for resizing, I feel confident when I say that at some point in time you will experience an “Oh s&#%” moment and have to find a way to break loose a stuck case that has been jammed tight up inside your resizing die. My best advice here is to not wait for this problem to occur. Go ahead and purchase a stuck case removal kit now to have on hand for when that moment strikes. These are simple little tools that generally cost less than $30, but they are certainly worth a bundle.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Lyman

http://www.lymanproducts.com; 800-632-2020

RCBS

http://www.rcbs.com; 800-379-1732