During the gangster era of the 1920s and 1930s, lawmen were forced to get more powerful weaponry to counter heavily armed criminals who sped from town to town robbing banks or committing other crimes. Often, these bandits used Browning Automatic Rifles (BARs) or Thompson SMGs as well as an array of pistols and revolvers. One problem lawmen faced was that their handguns, often .38 Special revolvers firing 158-grain, round-nose bullets, were not powerful enough to stop the vehicles in which gangsters fled their crimes, nor were they effective against the “bulletproof vests” worn by some criminals.

Colt introduced its .38 Super Automatic in 1929 as a counter to the “motorized bandits.” Built originally for the 1911A1, the .38 Super offered a 130-grain jacketed bullet that traveled at 1,280 fps. It was designed to penetrate body armor or heavy steel vehicle bodies. Though some major police departments purchased .38 Super semi-autos, law enforcement agencies were still oriented towards revolvers.

As a result, Smith & Wesson introduced its .38/44 Heavy Duty revolver in 1930. Some .38/44 loads used a special metal-piercing bullet at 1,125 fps, as opposed to the 755 fps of the standard .38 Special loading. To take the hotter load, the N-Frame revolver—normally chambered in .44 Special, .45 Colt or .45 ACP—was chambered for the new cartridge. In 1931, an adjustable-sighted version of the .38/44 was offered as the Outdoorsman. While the Heavy Duty was available with 4-, 5-, or 6.5-inch barrels, almost all Outdoorsman revolvers had 6.5-inch barrels.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Magnum Origins

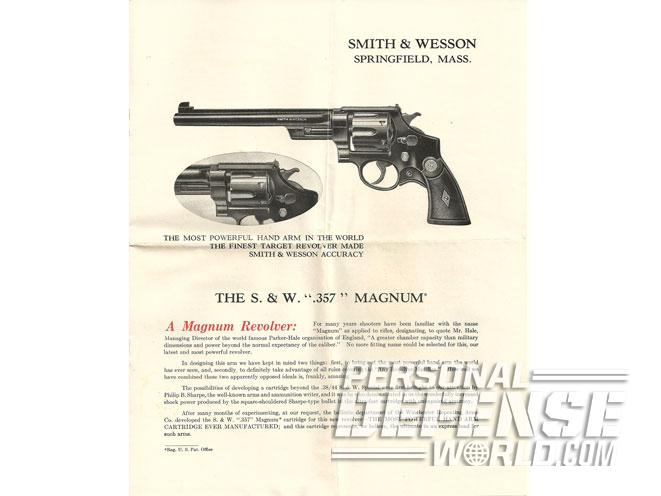

These cartridges and weapons helped local police and federal officers engage dangerous criminals more effectively, as did the Thompson SMG, the BAR and the Model 97 and Model 12 riot or trench guns. Although the gangster menace was abating by the mid-1930s, Smith & Wesson introduced what was advertised as the “Most Powerful Handgun in the World” in 1935—the .357 Mag. Using a cartridge developed by Remington with a 158-grain semi-wadcutter around 1,500 fps and with a case 0.135 inches longer than the .38 Special (meaning it would not chamber in .38 Special revolvers), the .357 Mag revolver had a recess for cartridge heads to give additional strength and a specially heat-treated cylinder.

RELATED STORY: 15 .357 Magnum Revolvers For Competition and Personal Defense

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

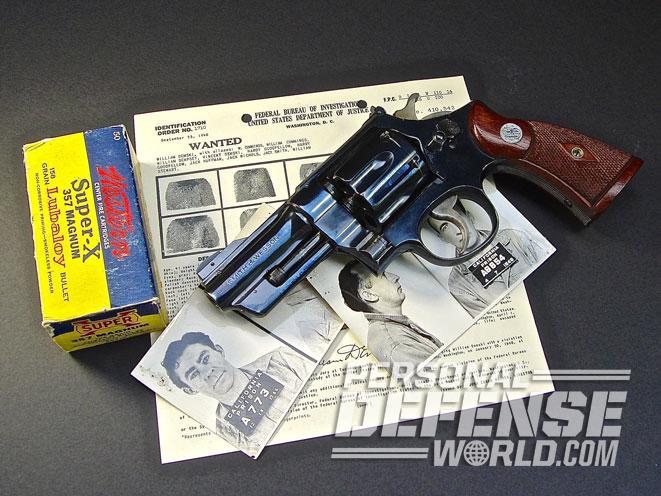

Designed to appeal to lawmen wanting the ultimate in handgun power, the first Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum revolver was presented to J. Edgar Hoover. The FBI later bought a substantial number of .357 Mags with 3.5-, 4- and 5-inch barrels, and many FBI agents purchased their own revolvers. Perhaps the most famous FBI user of the pre-war magnum was Walter Walsh, an FBI and USMC legend who died at 107 on April 29, 2014. Walsh used his magnum during a shootout with the Brady Gang in October 1937. Most FBI magnums were called in many years ago, but I know of at least one agent who found one in his office’s armory during the 1990s and continued to carry it until orders came from Quantico to send it back on pain of dismissal.

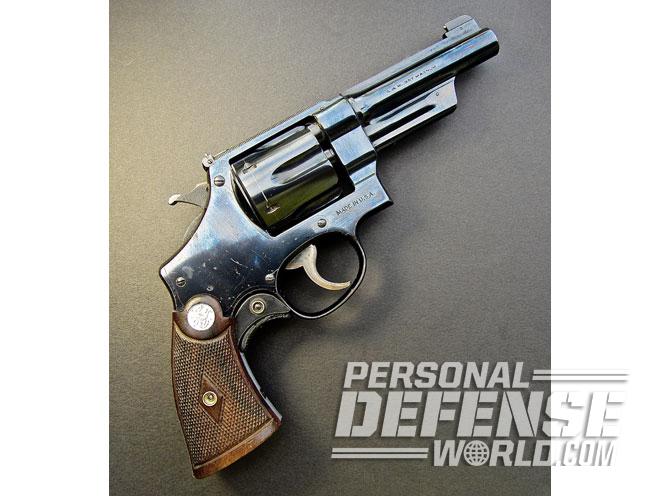

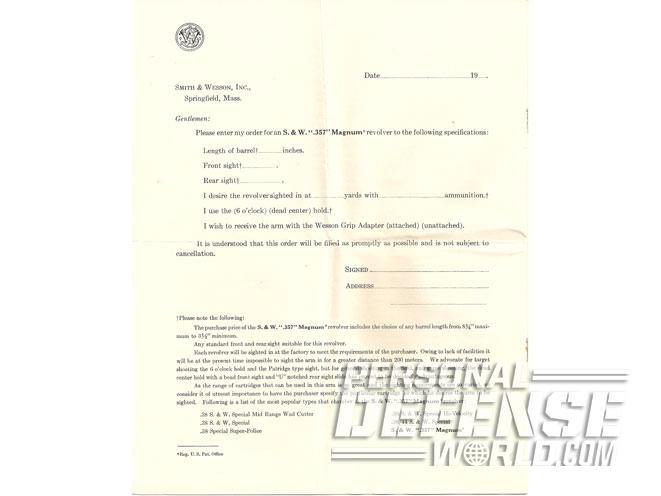

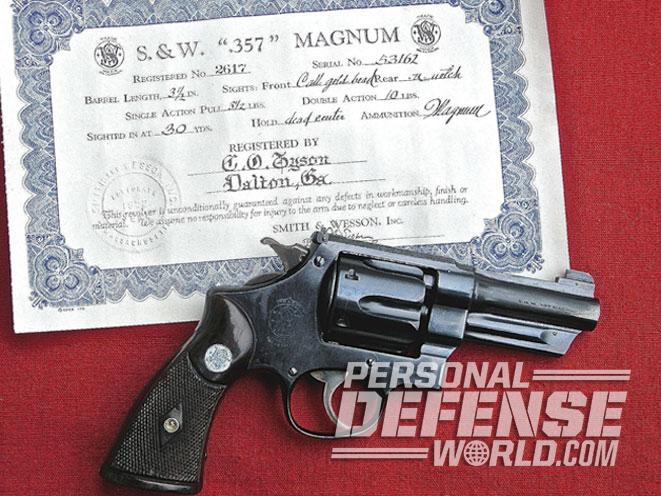

Each revolver could be ordered as virtually a custom gun. The buyer could specify any barrel length between 3.5 and 8.75 inches in 0.25-inch increments, the types of front and rear sights, the grips, the finish, trigger pull, and the distance at which the revolver was sighted. Each revolver had a registration number stamped on the revolver’s frame by the crane, and the buyer could request a registration certificate. Registration carried a lifetime guarantee. Because of the registration numbers, collectors refer to these revolvers as “Registered Magnums.”

RELATED STORY: Gun Review – Smith & Wesson Model 442 Moon Clip

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In October of 1939, S&W decided to discontinue stamping the registration number and to standardize five barrel lengths; however, other barrel lengths could be ordered for an extra $1. At a time when the S&W .38/44 Outdoorsman sold for $45, the Magnum sold for $60. That’s roughly $725.62 in 2015 dollars, but in the Great Depression, the actual buying power of $60 was much more. The average annual salary for those who were working in 1935 was $1,500. The pre-war .357 Mag was discontinued by S&W in December of 1940, when the company geared up for wartime production.

Law enforcement orders for the .357 Mag were usually for barrels of 3.5, 4 or 5 inches. However, individual lawmen ordered lengths that fit their preference. For example, it is estimated that over 100 were sold with 4.5-inch barrels, though not all to law enforcement. The most popular length was 6.5 inches, with an estimated 1,518 being sold. This length appealed to law enforcement personnel as well as outdoorsmen. About 10 percent of the .357 Mags sold went to law enforcement agencies. In addition to the FBI, one of the largest purchasers for police use was the Kansas City Police Department, which acquired 3.5-inch-barreled versions. Many FBI agents purchased 3.5-inch-barreled guns, including Frank Baughman, an FBI firearms instructor during the 1930s. Baughman designed his own ramped front combat sight for the S&W Magnum, a sight that is still known as the “Baughman front sight” today. Another fan of the 3.5-inch-barreled Magnum was General George Patton, who ordered one on September 9, 1935.

An array of other law enforcement officers used the pre-war magnum, including sheriffs, Border Patrolmen, Texas Rangers and more. For the average cop, though, the magnum was very expensive. Although this article focuses mostly on the Registered and Non-Registered pre-World War II magnums for law enforcement, it should be borne in mind that many were also purchased by sportsman for use against big game. They were more interested in stopping bears than criminals!

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

RELATED STORY: 5 Smith & Wesson Guns for Everyday CCW Self-Defense

For more information, visit http://www.smith-wesson.com or call 800-331-0852.