How many times have you been told that the minimum self-defense cartridge is a +P .38 Special? If that’s the case, then why do so many people successfully defend themselves with handguns chambered in .22 Short, .22 Long and .22 Long Rifle? A recent report of shooting incidents by police officer and defensive trainer Greg Ellifritz surveyed 1,513 shootings that took place between about 2001 and 2011. In 10.2 percent of the cases, the handguns used were non-magnum .22 rimfires. Even more surprising was that the “lowly” .22 had a very respectable 60-percent rate of one-shot stops. In an earlier street study covering the late 1980s to 2001, Evan Marshall and Ed Sanow gathered information on 4,483 shootings with the .22 LR. The most effective .22 LR cartridge in their study was the CCI Stinger, which produced a one-shot-stop rate of 38 percent. Street studies are not based on random sampling. This can cause differences in their findings. However, one can’t dispute that a minimum of nearly 4,600 shootings took place with non-magnum .22 rimfire handguns over approximately 30 years. Why are there so many shootings with .22 handguns? One reason is the large number of privately owned .22s. A report published in 2000 by the Bureau of Justice Statistics indicates that 10.7 million .22 revolvers and pistols were produced between 1973 and 1993. Add to that all the .22 handguns manufactured before 1973 and since 1993 and the total number could easily top 20 million.

“Concealed-Carry requires guns that are reliable, concealable, easy to carry and relatively simple to operate. That’s why I suggest eight-shot, lightweight .22 LR revolvers.”

“Concealed-Carry requires guns that are reliable, concealable, easy to carry and relatively simple to operate. That’s why I suggest eight-shot, lightweight .22 LR revolvers.”

RIMFIRE DEFENSE:

Given that .22 rimfires have less stopping power than almost all centerfire cartridges, why do people buy them for self-defense? Conversations I’ve had with people who own .22 handguns for protection indicate that are two primary reasons. First, there’s the low cost of .22 ammo. Even with today’s inflated prices, a .22 LR cartridge only costs 10 to 15 percent as much as a round of .38 Special +P. The other reason is the .22’s mild recoil. A 10-ounce S&W M317 J-Frame snubnose generates less than a foot-pound of recoil energy when firing high-velocity loads.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

An Airweight J-Frame .38 firing a +P cartridge produces 5.5 foot-pounds of recoil, which is about the same recoil as a 230-grain .45 ACP load fired in a full-size steel 1911. I’ve found that people who are small statured, new to firearms ownership or who have disabilities tend to prefer .22 rimfire handguns. Over the years, I’ve advised a number of friends and acquaintances who have purchased handguns. Like me, several were over the age of 60. Some had owned .38s and found the recoil and muzzle blast unacceptable, even with light loads. Another had arthritis in her hands and could not pull a heavy double-action (DA) revolver trigger or operate the action of any semi-auto. She came into the Florida Gun Exchange to trade a revolver with a 15-pound trigger pull. When she dry-fired a 3-inch Smith & Wesson Model 317 with a much lighter factory trigger, she immediately bought it.

CONCEALED CARRY .22s:

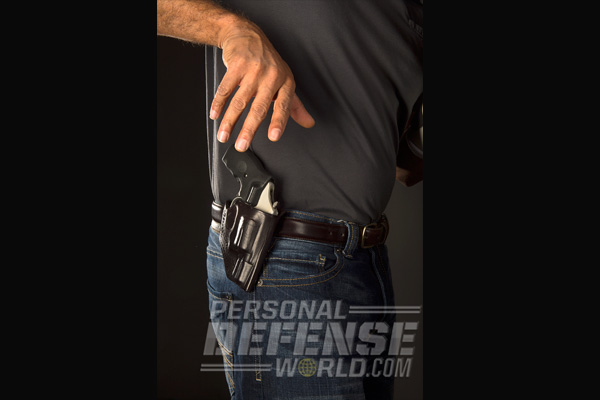

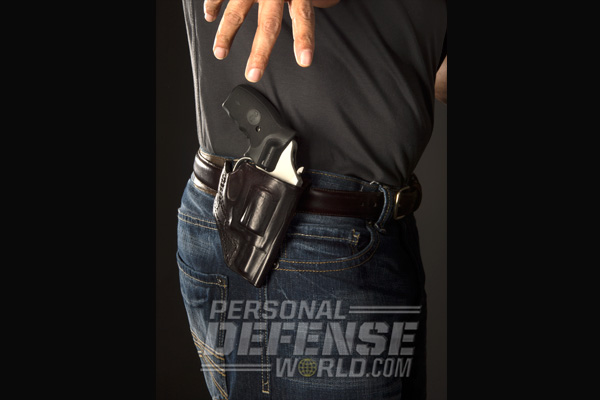

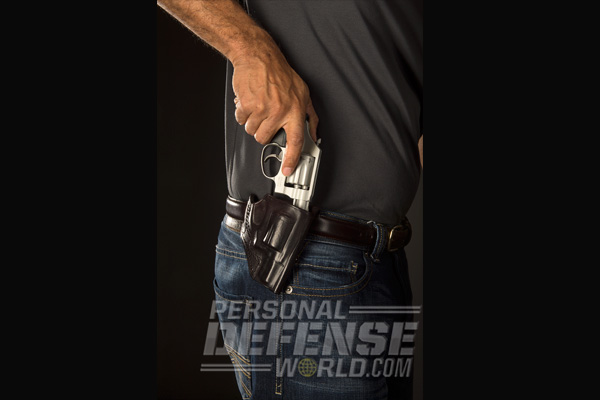

Just about any .22 rimfire handgun can be used for self-defense in a pinch, provided that the gun is in good condition and is designed for cartridges containing smokeless powder. On the other hand, concealed carry requires guns that are reliable, concealable, easy to carry and relatively simple to operate. That’s why I suggest eight-shot, lightweight .22 LR revolvers with 2- to 3-inch barrels to individuals who find it difficult to use centerfire handguns. There are a couple of reasons for this. First, rimfire revolvers tend to be more reliable than .22 semi-autos. Rimmed cartridges can tip and hang up when they are fed out of a magazine. This is particularly the case with high-velocity cartridges in small semi-autos with short slides that cycle quickly. Eight-shot revolvers have the same capacity as many small auto-loaders, and with eight-shot speedloaders, they can be reloaded just as quickly as the autos.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

There are several small, lightweight .22 revolvers that hold eight shots. Some of the most popular are S&W’s Model 317, Ruger’s LCR and the Taurus Model 94 Ultra-Lite. Any of these would meet the criteria for a personal-defense .22, but I like the S&W J-Frame Model 317 for a number of reasons. At 10.8 ounces, it’s the lightest eight-shot .22 snubnose revolver. In addition, gunsmiths are very familiar with the J-Frame action, and most find it easy to do a trigger job on it. Finally, the J-Frame model is supported by a large number of holsters and aftermarket accessories. The Model 317 used for this article has a 14-pound Wolff rebound slide spring installed, which gives it a smooth, 10-pound DA pull. It’s also been modified by painting the serrated rear surface of the front sight with orange Bright Sights paint. The final modification is a Crimson Trace LG-305 Lasergrip. It promotes fast, accurate shooting in low light. The grip’s red laser matches the color of the paint on the front sight. Because of this, the color of the aiming point is the same, day or night.

RANGE RESULTS:

The Model 317 carries and functions excellently. It conceals easily in a Rusty Sherrick holster under a light shirt. Rapidly firing in DA mode, the Model 317 easily placed shots in the center of the target at 7 yards. Fast DA headshots at that distance were also easy. As for ammunition, CCI’s Stinger works very well. It exited the Model 317’s 1.875-inch barrel at an average of 1,082 feet per second (fps). At this velocity, the Stinger generated 83 foot-pounds of muzzle energy. This isn’t a great deal, but it is higher than the 58 foot-pounds of energy that is cited in the NRA Firearms Fact Book as the U.S. Army’s threshold for causing a disabling casualty. In actual shootings, Marshall and Sanow found that the Stinger didn’t mushroom.

It flattened to .28 caliber and penetrated an average of 7.5 inches in 465 recorded shootings. Other .22 loads penetrated more deeply, but only one came close to meeting the FBI’s minimum standard of 12 inches. One of the .22 LR’s limitations is that it is much better suited for frontal shots rather than quartering or cross-torso shots. In addition, thin rimfire brass can swell easily and tie up a revolver if the cartridge is overloaded. However, I’ve yet to have a Stinger fail to fire in a revolver, never had one over-expand and have not had one of the nickel-plated Stinger cases fail to extract.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

FINALE NOTES:

The .22 LR isn’t the best choice out there, but for some people it’s the only handgun they can shoot accurately—or at all. It is surprisingly effective in street studies, and when push comes to shove, Mark Moritz’s “First Rule of a Gunfight” applies—have a gun!

For more information, visit:

smith-wesson.com or call 800-331-0852

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

cci-ammunition.com or call 800-379-1732