Like the Pioneers, Smith and Wesson Staked a Claim on the American West

In Springfield, Massachusetts, a new company had emerged out of a partnership formed by firearms designers Horace Smith, the former production supervisor for Robbins & Lawrence in Windsor, Vermont, (a contract arms maker producing a version of the Model 1841 U.S. Percussion Rifle for the government in 1848), and Daniel B. Wesson, a young man from a family of gunmakers. Daniel’s older brother Edwin was already an established arms maker in Massachusetts by the 1840s, and his younger brother Frank would later create his own famous line of single-shot firearms.

Tragically, Edwin died of heart failure in 1849 shortly after Daniel had completed his apprenticeship. Unable to keep his late brother’s business going on his own Daniel took a superintendent’s job with Leonard Pistol Works, and as fortune would have it, Leonard pistols were made under contract by Robbins & Lawrence. In time, Mr. Smith met Mr. Wesson.

The two first began working together on a project for Courtland C. Palmer, a wealthy philanthropist and speculator who had purchased the rights to the Jennings Patent Rifle which didn’t function properly and was sent to Robbins & Lawrence to be sorted out. It was Horace Smith who did most of the sorting and in 1851 the Smith-Jennings rifle was patented. In the interim, Smith and Wesson were becoming good friends.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Among Daniel’s passions was a new French rifle design, essentially a gallery gun used for indoor target shooting that fired a tiny lead ball contained in a cartridge designed by Louis-Nicolas Flobert. The cartridge was comprised of a brass case with a touch of fulminating mercury in its base, a few grains of black powder, and a tiny round lead ball. When the brass cartridge was struck by the hammer of the gallery gun, the fulminating mercury ignited sending a spark into the powder charge which exploded and sent the little lead ball rolling down the chamber to its intended paper or metal target.

Soon Smith became infatuated with the idea as well as Palmer, who offered an additional stipend for Smith and Wesson to design an American version. Their idea was a “saloon pistol” based on the Flobert but using a design that they devised allowing multiple shots and the chambering of rounds using a ring lever (toggle link) action similar to the Smith-Jennings rifle. What they arrived at would not only change the way rifles were to be made for the better part of the 19th century (and into the 21st century) but the very notion of how they would be loaded and with what.

Two pivotal developments arose out of Horace Smith’s and Daniel Wesson’s collaboration in 1854. The first was a pistol design that would evolve into the Volcanic, and the Volcanic Repeating Arms Co., which would become the foundation for the New Haven Arms Co. and eventually Winchester Repeating Arms. The second was Daniel Baird Wesson’s development of the .22 caliber short, the first American-made metallic cartridge, for which Messrs. Smith and Wesson received a patent on August 8, 1854.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

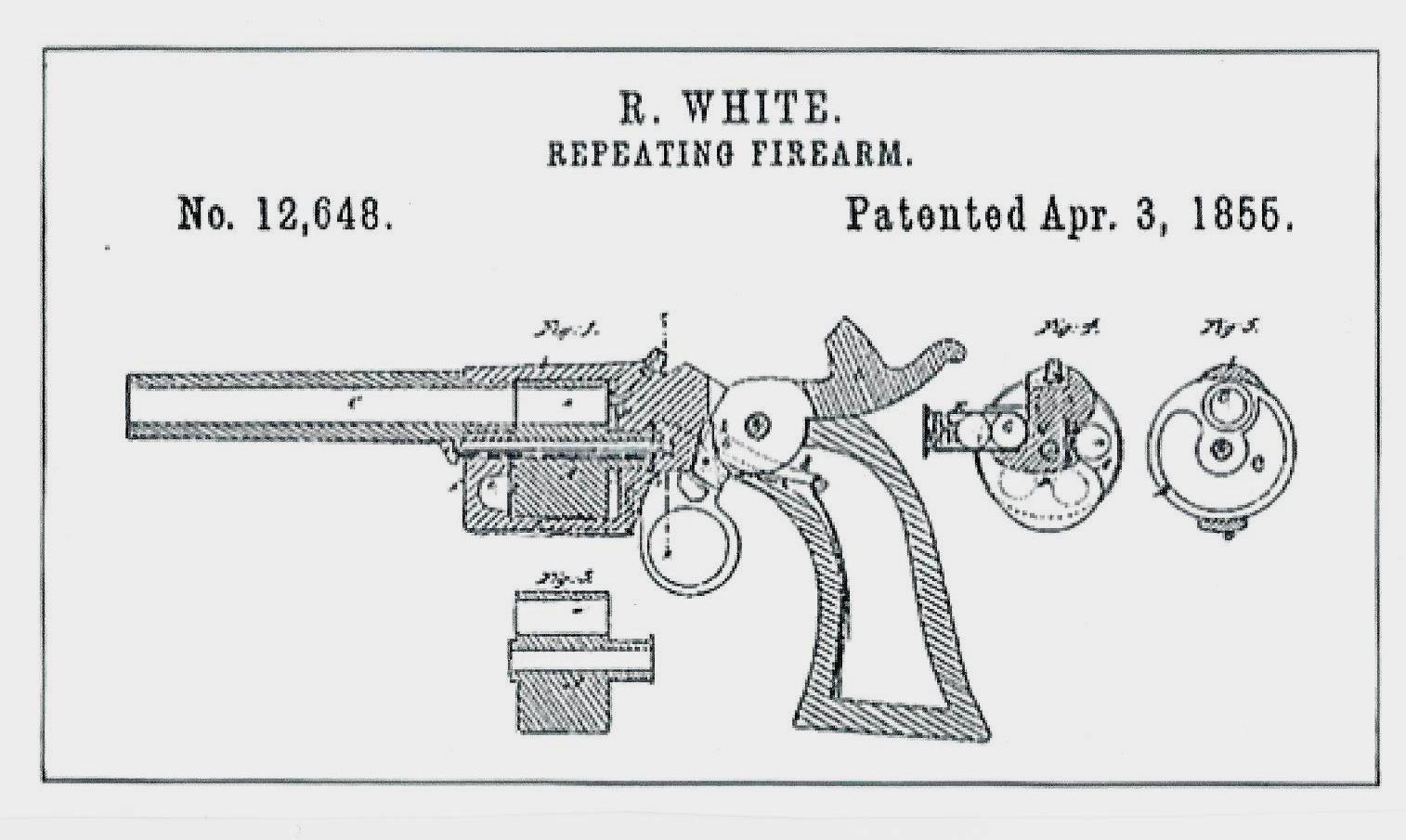

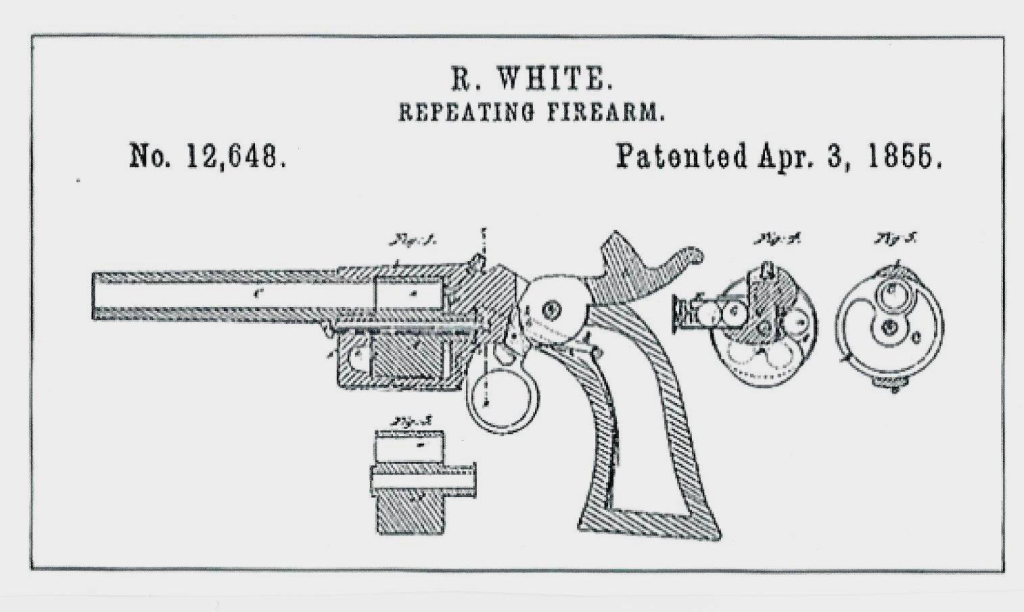

The Rollin White Patent

By 1856, fate, in the guise of inventor Rollin White, was about to enter Smith and Wesson’s lives. Daniel Wesson had seen White’s patent filing for the bored-through cylinder and sent him a letter of inquiry, writing, “I notice in a patent granted to you…one claim—viz—extending the chambers of the rotating chamber right through the rear end of said cylinder so as to enable the said chambers to be charged from the rear end either by hand or by means of a sliding charger.” The letter brought White to Smith & Wesson’s door. After a meeting, in which it was explained that S&W held the patent rights for the bullet that would fit White’s cylinder, an agreement was reached that would give Smith & Wesson exclusive license to the White patent in exchange for a .25 cent royalty on every cartridge-firing handgun they manufactured.

In 1857 when Colt’s revolver patent expired, S&W came to market with their first model, but more importantly, it was America’s first breech-loading, cartridge-firing revolver; a design that no arms maker in the United States would be allowed to copy for the next 12 years! Between 1857 and 1869 when the White patent expired, Rollin White earned more than $70,000 in royalties.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

S&W’s First Model No. 1 was produced through 1860 when it was replaced by the improved No. 1 Second Issue, which remained in production until 1868. With the beginning of the Civil War orders for the little 7-shot .22 caliber revolvers soon exceeded production capability. And it was just as well that the Ordnance Department did not regard the S&W .22 as a worthwhile sidearm for the Union Army, as civilian demand was enough. Nevertheless, in June of 1861 Smith & Wesson introduced the Model 2, a more powerful 6-shot .32 caliber version.

With barrel lengths of up to 6 inches, the medium frame spur trigger belt-sized pistol was suitable for carry in a small holster or tucked into the waistband. Even the No. 2 was not regarded as a powerful enough pistol by the Ordnance Department to consider as a military sidearm. The same, however, could not be said for individual soldiers.

The .22 Short S&W Model No. 1, .32 rimfire No. 2, and the smaller Model No. 1-1/2 (introduced in 1865), also chambered in .32 rimfire, were among the most highly demanded backup guns for Union officers and infantrymen, even though they had to purchase them with their own money. The No. 1-1/2 was manufactured through 1868, while high demand kept the No. 2 in production until 1874. Among the famous owners were Wild Bill Hickok, Rutherford B. Hayes, and General George Armstrong Custer. Hickok carried the No. 2 in a vest pocket as his backup gun.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Post-Civil War Era

By the 1870s the self-contained metallic cartridge introduced by S&W had grown from an anemic .22 Short in 1857 to the man-stopping .45 Schofield by the 1870s. Somewhere in the middle was the popular .38 caliber round, and in 1876 S&W introduced a pocket model in .38 S&W caliber. The pistol looked like a smaller version of their Top-Break .44 S&W Model No. 3 American single action but with a spur trigger and no trigger guard. Originally known as the Model 2, the new little .38 relegated the Civil War era .32 rimfire Model 2 to the status of “Old Model No. 2,” or “Old No. 2 Army.” S&W’s first .38 centerfire pistol also picked up a rather catchy nickname of its own, “Baby Russian.”

The .38 S&W Baby Russian was a one-year-only model accounting for 25,548 sales before being replaced by the improved .38 Single Action 2nd Model in 1877. In 1878 S&W introduced another Top-Break model chambered in .32 S&W caliber and cataloged as the No. 1-1/2. (Oddly enough, no one calls the original .32 rimfire No. 1-1/2 the “Old Model No. 1-1/2”).

In 1891 the 3rd. Model .38 Single Action, with an added trigger guard, was introduced. By the early 1890s Smith & Wesson had produced more than 97,000 revolvers chambered in .32 S&W and 108,225 2nd Models in .38 S&W. Carrying over into the 20th century, total production for the 3rd. Model .38 S&W reached 26,850 by the time it was discontinued in 1911.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Large Caliber S&Ws

S&W beat Colt to the draw in 1870 by introducing the first all-new large caliber cartridge revolver produced in America, the .44 caliber S&W Model 3 American. The Model 3 name was S&W’s classification for its large frame revolvers (just as N Frame designates a large frame S&W today). The Top-Break single action was faster to handle, load, and unload than any other handgun up to that point in time. When broken open the S&W simultaneously ejected the shells in all six chambers. (Unfortunately, it also ejected any unfired rounds if opened prematurely.)

The Model 3 American was chambered in both .44 rimfire Henry, though only around 200 were produced, and in .44 American (also known as .44 S&W or .44/100). This was the model carried by Virgil Earp in Tombstone and handed to Wyatt at the time of the shootout at the O.K. Corral, or at least that is one version of the story. Cowboy and stage actor Texas Jack Omohundro, who performed in Buffalo Bill Cody’s original theater troupe, also carried this model. El Paso, Texas, City Marshall Dallas Stoundenmire carried a No. 3 First Model, as did Texas Ranger L.H. McNelly, and last, but not least, famous outlaws Jesse James, and John Wesley Hardin.

The next .44 in the line was the 2nd Model American which differed in the frame design with a bump in the bottom of the frame to accommodate a larger trigger pin. The 2nd Model American also bore a number of minor exterior modifications made to No. 3 models produced under contract for the Russian military, including a locking hammer and barrel latch, new style barrel hinge and screw, and a steel front blade sight replacing the original German silver front sight, and a detachable shoulder stock was offered for the first time.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The 3rd variation was the New Model No. 3 manufactured from 1878 to 1908 with a standard barrel length of 6-1/2 inches and chambered in .44 Russian. Barrel lengths varied from 3-1/2 inches to 8 inches, and a detachable shoulder stock was again available. The model was also produced in .32-44, .38-40, .44-40, and .320 caliber for the revolving rifle variation. Between 1870 and 1912 total production for No. 3 Americans, the New Model No. 3, New Model No. 3 Frontier, and foreign contract production (aside from Russian military contract models) totaled over 110,700 guns.

The Russian & the Schofield

Although the vast majority of sidearms carried by the U.S. Army in the 1870s were Colt Single Actions, S&W also provided a significant number of Top-Break models for the Cavalry beginning in 1870. The most noteworthy was a variation designed specifically for the mounted soldier, the Schofield. This version, chambered in a new caliber, .45 Schofield, arrived in 1874 as an improved No. 3 American designed by U.S. Army Colonel George W. Schofield.

The first .44 caliber S&W revolvers used by the U.S. Army in 1870 had been criticized for the top-break design, which had the barrel-mounted release latch. This often proved hard to use on horseback. Schofield, then a Major, redesigned the latch mechanism to fit on the frame instead of the barrel, and thus release the barrel by simply pulling the latch back (with the hammer at half cock) and pressing the barrel down against one’s leg (or other surface) to pivot it open.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The U.S. Ordnance Dept. ordered almost the entire production of this distinctive S&W model. The standard barrel length for the Schofield was 7 inches. There was only one drawback to the S&W, from a military logistics standpoint. The .45 Schofield was a different size than a .45 Colt. The cartridge would fit into a Colt SAA but a .45 Colt round was too long for the Schofield’s cylinder. Ultimately that led to Colt becoming the dominant U.S. military sidearm.

For sale to the civilian trade, a number of military Schofields were refinished and altered to barrel lengths of 4-1/4 inches. Others were specially built with 5-inch barrels for use by Wells Fargo & Co. agents, as well as surplus guns with cut-down barrels sold through New York retailers Schuyler, Hartley & Graham, and Francis Bannerman & Co. Total Schofield production in all variations accounted for approximately 8,969 guns.

The S&W Russian Models were an overwhelming success if not an oddity in that the redesign of the No. 3 American’s grip strap and trigger guard was to accommodate the requirements of the Russian military. Thus if there is one Model 3 that is easily distinguished from another it is the Russian!

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Russian variation (which later influenced changes in the Second Model American) was chambered for a new cartridge, .44 S&W Russian. This was a different caliber in that the .44 S&W round used an outside lubricated heeled bullet of equal diameter to the case whereas the .44 S&W Russian used a larger case diameter than the bullet. This eventually became the dominant caliber for S&W Top-Break models.

The Russian model had a large knuckle at the top of the backstrap to rest over the web of the shooter’s hand, a severely angled grip, round bottom, a lanyard ring, and a most distinctive trigger guard spur. There were three Russian variations, the first almost identical to the No. 3 American except for caliber, and the second and third with the aforementioned changes to the grip and trigger guard configurations.

Russian barrel lengths ranged from 5-1/2-inches to 8-inches with 2nd. and 3rd. Models are generally offered in 7-inch and 6-1/2-inch lengths, respectively. In total, all Russian variations manufactured from 1871 to 1878 reached 131,138 guns, making the Russian models plentiful even to this day. And this does not take into account S&W copies made in Russia at the Tula Arsenal and in Germany by Ludwig & Lowe, which adds another 400,000 to 500,000 guns, even though they are not S&Ws.

According to S&W historian Roy Jinks in his book 125 Years with Smith & Wesson total Model 3 production in all variations reached 250,820 by 1912.

Double Action S&Ws on the Frontier

S&W has long been the most recognized name in double action revolvers, but in the 19th century they were a little late to the game, not introducing their first DA models until three years after Colt’s, but when the Springfield, Massachusetts, arms maker got on the bandwagon they quickly became the leader of the parade, a position S&W has not relinquished in more than 135 years.

When it comes to variations, S&W double action models from the late 19th through early 20th centuries could fill a book on their own. The first models c.1880-81, were the wellspring for several of the finest and most advanced handguns of the Old West. The first models were all Top-Break designs and offered in different frame sizes and calibers.

S&W’s first double action model was chambered in .32 caliber centerfire, a traditional round dating back to the original Tip-Up .32 rimfire No. 2 revolvers of the Civil War era. The new 5-shot, .32 caliber guns eschewed their predecessor’s spur trigger design for a new frame incorporating a full trigger guard with a reverse curve at the rear. It is estimated that only 30 examples were built before S&W replaced it with an improved 2nd Model in 1880. The popular .32 caliber revolvers were manufactured in five model ranges, the 1st Model in 1880; the 2nd Model 1880-1882; the 3rd Model 1882-1883; the 4th Model 1883-1909; and the 5th Model 1909-1919.

The 2nd Model differed in the side plate design (curved rather than straight where the grip straps meet the frame), the top of the barrel was ribbed, rather than round, and the hard rubber grips bore the S&W monogram for the first time. The guns were offered with a standard blued finish or an optional nickel-plated finish. All models, regardless of finish had blued reverse curved trigger guards.

When the 3rd Model was introduced in 1882 there were a number of design changes including optional barrel lengths of 3 inches, 3-1/2 inches, and a long 6-inch version. The cylinder design was all new and featured longer flutes. Retained from the 1st and 2nd Models were the blued trigger guards, pinned round blade front sight, and notch rear sight cut into a raised portion of the barrel latch.

The most distinctive change in the 4th Model, introduced in 1883, was a new rounded trigger guard without the previous reverse curved rear (but still with blued finish), and the option of 8-inch and 10-inch barrels, which are regarded today as “very rare.” The 5th and final .32 caliber model arrived nine years after the turn of the century and had minor changes to the established design, which included an integral front blade sight and a new S&W trademark stamping on the right side of the frame. Available barrels were the standard 3-inch, 3-1/2-inch, and 6-inch lengths. Production of S&W .32 caliber double action revolvers reached more than 328,600 by 1919 making it one of the most popular small handguns on the market.

In 1880 S&W also began production on a double action Top-Break chambered in .38 centerfire, and a year later, their first .44 caliber double action model was introduced. The .38 resembled the first .32 caliber models with a 5-shot fluted cylinder. The .38s had a distinctive square back reverse curved trigger guard. Like the 1st Model .32, the original .38 had a short production run (about 4,000) and was replaced later in 1880 by the 2nd Model incorporating the same modifications made to the .32 caliber guns. Barrel lengths were 3-1/4 inch, 4-inch, 5-inch, and 6-inch, blued or nickel finishes. Like its smaller caliber companion, the .38s also had blued trigger guards regardless of finish.

S&W’s 3rd Model .38 Top-Break Double Action Revolver was introduced in 1884 and remained in production for 11 years becoming one of the most prolific .38 caliber DA handguns in America, with a total production of over 203,000. Standard barrels ranged from 3-1/4 inches to 6 inches with 8-inch and 10-inch barrels also available.

The 4th Model mainly featured mechanical improvements to the trigger mechanism, the availability of target sights with an adjustable rear sight, and available target grips. Following the success of the 3rd Model, the 4th Model .38 DA was produced from 1895 to 1909, with sales totaling over 216,000 guns.

The 5th Model arrived in 1909. Almost a continuation of the 4th, it featured barrel lengths as short as 1-1/2 inches, and standard lengths of 3-1/4 inches, 4-, 5- and 6 inches. The round blade front sight was integral with the barrel, target sights and target grips were also available, and finishes remained blued or nickel. The 5th Model was short-lived, with just 15,000 examples, as Smith & Wesson was about to introduce one of the most important design changes in its early history, the c.1909 transitional Double Action Perfected.

The .38 caliber Perfected was to be S&W’s last Top-Break and the only one to have an additional side thumb piece release which had to be pressed forward in order to break open the action, eject spent cartridges, and reload. This device would not be used on the first c.1896 Hand Ejector models with swing-out cylinders, but would appear shortly after the turn of the century, beginning in 1903, with the new Hand Ejector S&W revolvers.

While .32 and .38 caliber double action revolvers were in high demand, it was anticipated S&W would be forthcoming with a .44 caliber double action revolver. The first model arrived in 1881 on the heels of the smaller caliber DA models. Looking like a large .38 caliber S&W double action, right down to the reverse curved trigger guards, the Double Action Frontier Model was chambered in .44 S&W Russian and .44-40 Winchester, and a small quantity in .38-40. The big six-shot revolvers were offered with barrel lengths of 4-, 5-, 6- and 6-1/2 inches. Like the .38 caliber guns, the large caliber six-shooters had checkered hard rubber grips and were available in blued and nickel-plated finishes. Production of the 1st Model continued through 1913.

The .44 caliber double action Smiths had one variation produced in 1882-1883 known as the .44 D.A. Wesson Favorite. About 1,000 were produced in what can best be described as a lightweight variation with grooves cut into the sides of the frame to reduce mass, a smaller cylinder diameter in front of the flutes, and a narrower diameter 5-inch barrel. All of these special models were chambered in .44 S&W Russian.

The frames for all Top-Break .44 S&Ws had been built by 1899 with a total of around 54,000 produced. Sales, however, lasted well into the early 20th century by which time Smith & Wesson had introduced the Model 1896 chambered in .32 S&W Long. Also known as the S&W .32 Hand Ejector 1st Model, (also Model I Hand Ejector) this was the first S&W to employ a swing-out cylinder for the ejection of spent shell cases, loading and reloading.

The 6-shot revolvers were offered with 3-1/4 inch, 4-1/4 inch, and 6-inch barrels from 1896 through 1903. This first swing-out cylinder design used a spring-loaded cylinder pin to lock the cylinder in place. It was released by pulling the pin forward and pressing the cylinder towards the left side of the frame.

The most unusual feature of the 1st Model revolvers was the location of the cylinder stop, in the top strap with the rear sight mount forward of the cylinder’s centerline. When the trigger was pulled to rotate the cylinder, or when the hammer was manually cocked, the top strap (and thus the rear sight) raised slightly through the action of cylinder rotation. This was the predecessor to the I- and J-Frame models. The first K-Frame in .38 S&W was introduced in 1899.

The 1st Model (Triple Lock) and 2nd Model .44 Hand Ejectors were introduced in 1908 and 1915, respectively, and featured solid frames, side-swing cylinders and used a thumb piece release on the left side of the frame. The guns were available in calibers up to .45 Colt (including .44 S&W Special, .44 S&W Russian, .38-40 Winchester, .44-40 Winchester, .45 S&W Special, and British chamberings of .455 Mark II and .450 Eley).

One More Variation

Not satisfied to rest on their very successful laurels, Messrs. Smith and Wesson had ventured off into yet another direction in 1888 with an entirely different design for double action revolvers, a gun that came to be known as the Safety Hammerless.

The 1st Model Safety Hammerless had its design firmly rooted in the American West. The .32 caliber and .38 caliber Top-Break revolvers were the work of Daniel B. Wesson and featured a backstrap mounted safety bar, which, when depressed by firmly grasping the gun, made the double-action-only revolver operable. Without depressing the bar the gun would not work. It was intended to prevent an accidental discharge if dropped, a problem that afflicted many 19th-century revolvers and led to the wise practice of keeping the hammer resting on an empty chamber. Those who abided by this turned their six guns into five-shooters, and in the case of smaller models, cartridge capacity dropped from five to four.

Wesson’s design allowed a fully loaded revolver to be carried without the fear of accidental discharge. The internal hammer design had one other advantage; in a tight situation, the gun could be fired from within a coat pocket without the risk of a hammer spur or firing pin getting caught up. This had a great appeal to those on both sides of the law, and especially to women who could easily carry a snub nose .32 Safety Hammerless model hidden within a purse or clutch.

Between 1888 and 1940 Smith & Wesson sold more than half a million Safety Hammerless Top Breaks. Over 240,000 were chambered in .32 caliber and another 261,000 in the more powerful .38 S&W caliber, which remained in production after the .32s were discontinued in 1937.

Interestingly, since 1896 when S&W introduced the first Hand Ejector with a swing-out cylinder, Top-Break revolver sales had been declining, with the exception of the Safety Hammerless. One reason Safety Hammerless models continued to sell in the early 20th century was that they offered a shorter barrel length of 2 inches, compared to the shortest standard Hand Ejector barrel length of 3-1/4 inches.

It wasn’t until 1915 that S&W began offering the .38 Military & Police Model with a 2-inch barrel. By the early 20th century S&W had come a long way from its first 7-shot .22 caliber rimfire pocket pistol, firmly establishing a reputation that has kept Smith & Wesson at the forefront of American arms-making since the days of the Civil War and the American West.