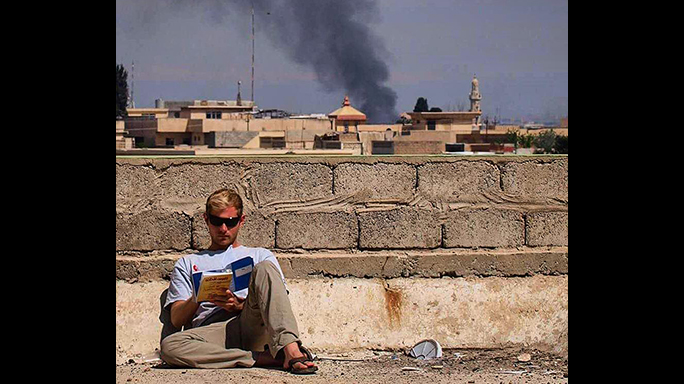

The following is an Athlon Outdoors exclusive with Nik Frey, a 22-year-old surfer from Southern California who suddenly dropped everything and became a medic in Mosul.

If I told you that I spent my last month embedded with the Iraqi Special Operations Forces (ISOF) treating civilian and military casualties in the Battle of Mosul, you might assume that I’m a soldier, operator, contractor or at least a veteran who has operated in war zones before. If I clarified that my role in Mosul was strictly medical — to save as many lives as close to the frontline as possible — you may assume that I’m a certified doctor or at least a senior paramedic. Or perhaps that I’m a well-connected war correspondent. In fact, I’m none of these things.

I’m nobody special. I’m a 22-year old surfer and outdoor-sports enthusiast who recently graduated from a beach-town university in California with relatively useless degrees in political science and writing.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Although I’ve worked as a lifeguard and have an EMT-basic certification under my belt, I’ve never been paid to drive an ambulance and I’ve never been on track for medical school. Besides what I learned as an Army ROTC cadet in college (a career path I chose not to pursue), I had very little practical experience in treating combat trauma or warfighting in general. However, I did know that Iraqi/Kurdish civilians and soldiers fighting ISIS were dying daily and that modern understanding of emergency medicine in Iraq is incredibly lacking. So when I heard about a group of rogue medics from around the world who were literally saving lives in Iraq, I decided I was going to join them if they were willing to take me.

Packing My Bags

I abruptly quit my job in the Midwest and traveled back to Southern California to meet a leader of the “Academy of Emergency Medicine” (AEM) — a 27-year-old named Derek Coleman, who had originally left for Iraq to fight ISIS with the Kurdish Peshmerga in November 2015 — during his brief hometown visit in San Diego.

It was a very short meeting; I basically caught Derek for 30 minutes while he was hanging out with his folks at a pizza parlor. Since our original plan to officially meet one-on-one at a coffee shop was intercepted by the FBI (they kindly interrogated Derek on the same week that Trump initiated his travel ban), this was really the only opportunity to meet the guy that I would quite literally be trusting my life with in Iraq.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Derek had become somewhat of a local legend by this point in San Diego and was known on international news as “the American who saves lives in Iraq.” Even though most of the other volunteer medics on Derek’s team were military veterans or experienced EMS personnel, he was cool enough to take a chance on a relatively inexperienced civilian like me and invited me to join his squad for the upcoming spring offensive of western Mosul.

The more hands on patients the better; my recent EMT training and ability to follow English instructions from the more-experienced guys on my team would make me useful. I immediately canceled my plans for a surf trip across Africa and made this Iraq option my biggest priority.

Although there was of course a major risk factor in going — Derek’s team had been targeted numerous times by ISIS snipers and mortars — Derek informed me that my physical presence in Iraq could literally result in lives being saved. Where I would be going, there are no doctors.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

If something happened, I would be reliant on my team and the Iraqi military for medical evacuation and security. I could die; Derek didn’t sugar-coat that possibility at all. Some of the AEM medics carry weapons (usually standard AK-47s) not for offensive “door-kicking” operations, but for self-defense in case things go south. I had only been shooting a few times with my Army buddies, so I knew I wouldn’t be much use to my team if ISIS launched a counterattack on our position.

I remembered watching the viral video of Iraqi military fleeing from ISIS in Ramadi back in 2015; these are the same guys I would be trusting my life with in Mosul. All things considered, the whole package scared the shit out of me. I had to go.

I’ve always respected those who lead with their actions, not just their mouths, and I knew that it simply was not enough for me to talk about the conflict in Iraq on social media or in a cozy college classroom. Besides, what was the point of writing a thesis on the value of humanitarian intervention in hotspots if I was too afraid to go myself? Bypassing this opportunity would only make me a coward and a hypocrite. I had to help.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Since I couldn’t afford the full cost of plane tickets and my parents sure as hell weren’t going to throw me money to potentially die in Iraq, I made a GoFundMe page. Thanks to those who donated, my travel costs were covered in a week.

Former Green Beret and Athlon Outdoors Tactical Field Editor, Aaron Barruga, hooked me up with his plate carrier to wear for personal protection and two of my Army friends even bought me a new GoPro to document my team’s work in Mosul. As soon as the money came through, I booked a flight to Iraq.

The Front Lines in Mosul

My experience as a volunteer medic in Iraq was the best experience of my life. I’ve traveled and contributed to humanitarian projects in various places around the world, but none of those experiences were as worthwhile as this one. Although I was surrounded by human suffering and some very gnarly circumstances near the frontline, I honestly enjoyed every minute of my time in Iraq.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

My team received numerous civilian and military patients as we worked hard to control bleeding and establish airways as quick as possible. We sent our critical patients to field hospitals run by large humanitarian organizations (which were often quite far away) in donated ambulances driven by local Iraqi civilians. These ambulances would speed across incredibly rough terrain and were sometimes shot at by ISIS snipers.

I served side-by-side with ISOF medics who provided food for us at our CCPs (Casualty Collection Point; also known as a TSP, or trauma stabilization point), which were usually schools and mosques recaptured from ISIS. It was surreal to become friends with soldiers from a country that my country had invaded when I was a child.

We occasionally received mortar fire, became targets for suicide vest attackers, and were even targeted by commercial drones carrying explosives that were piloted by ISIS informants. Regardless, nobody on my team got hurt and for that I am grateful.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Interesting enough, we operated closer to the frontline than most Special Forces medics from foreign militaries. Free of political restrictions that normally keep military units in strict “advising” roles, my team moved freely across Iraqi checkpoints throughout Mosul — thanks to connections our leadership has made throughout the conflict — and enjoyed autonomy that most government agencies and employees, included UN personnel, simply do not. It’s odd to realize that I was on a team that the United Nations and foreign media agencies often come to inquire about the situation in Mosul.

- RELATED STORY: 6 Phrases the Tactical Community Should Abandon Immediately

My experience in Mosul was nothing compared to the guys on my team who have been in Iraq since 2015 and who are staying for the long-term until ISIS is completely defeated. As the youngest medic on my team with the least experience in EMS and war in general, I was just lucky they were willing to drag me along.

If I could become part of a humanitarian mission I cared about, anyone can. My generation of millennials receives a healthy amount of criticism for being narcissistic, social media “slacktivists” who are vocal behind computer screens but lack true commitment to action. I think that’s bullshit. I know plenty of people my age doing incredible acts of service in their own communities and around the world. Every generation has lazy, and conceited underachievers, but instead of focusing on their lack of achievement, let’s instead empower those that are willing to make a difference.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The following is a list of excuses I had to confront before committing to volunteer service in Iraq. I hope this provides some insight to my peers. If you want to do something, just do it. It really is that simple. You don’t have to do something as risky as going to a war zone, but you can still make a positive difference in the world. The choice is yours.

Excuse No. 1: I’m Not Qualified

Find a mission or service opportunity that excites you and if it demands certain qualifications you don’t have, get qualified! For me, the basic EMT certification in the United States is respected worldwide and can qualified me for some incredible opportunities. Other options, like Wilderness First Responder (WFR) or Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC), are also great courses offered to civilians. Even if you are not interested in providing first aid in Iraq, there are globally recognized certifications that can be used in a variety or roles.

Excuse No. 2: I Can’t Afford It

As a recent college graduate, I was both broke and in debt when I decided to serve as a volunteer medic in Iraq. If you’re willing to take a leap of faith— like running a marathon to raise funds for cancer research or traveling to a developing country to provide job-training in the industry you have experience in— many organizations (universities, churches, news agencies, etc.) and friends of yours will likely be willing to help fund your trip. Try starting a GoFundMe! If an international service trip is out of your budget, consider cruising over to the homeless shelter in your own town to serve an often-ignored community of people— many of which are veterans who sacrificed for you in hostile lands before you were born. You don’t need to be a millionaire to make your time on Earth significant.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Excuse No. 3: My Family/Friends Won’t Approve

Are you 18 or older? If the answer to that question is yes, then who cares? You’re an adult and can make your own decisions. My parents obviously weren’t stoked about me going to Iraq, but when I finally affirmed them of the reality that I was going, my mother ended up coming to Iraq to serve in a different capacity in a Kurdish-Yazidi IDP camp. Most people are afraid to do things because they are too busy caring about what other people think or heeding the advice of people who are unwilling to or too afraid to make the step you want to take. If you want to do something “out of the ordinary” in the service of others, just do it.