By Peter G. Smithurst

After witnessing the carnage of the early stages of the Civil War, Richard Jordan Gatling, in his own words, wanted to create a weapon that would, “by its rapidity of fire, enable one man to do as much battle duty as a hundred, that it would…supersede the necessity of large armies.” It was a noble thought but a forlorn hope. Instead, what he created became an icon, culminating in a variety of small weapon systems with arguably the most devastating firepower capability in the modern military arsenal.

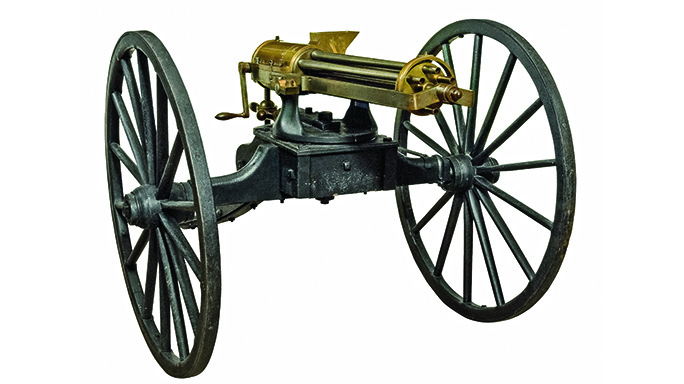

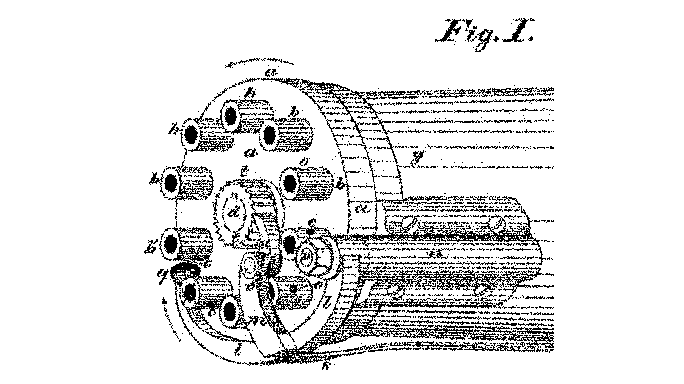

On November 4, 1862, Gatling was granted his first patent for a “machine gun.” It contained what became the familiar multiple barrels, each with its own firing and cartridge mechanisms clustered around a central shaft, all rotating when the gun was operated. To protect the locks from damage or the elements, this portion of the assembly was contained within a cylindrical casing.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After building a prototype, in 1862 Gatling moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, and eventually had 12 guns manufactured by McWhinny, Rindge & Company. These first guns used preloaded iron “chambers” fitted with external percussion caps.

But by this time the self-contained metallic cartridge had made its debut, and Gatling began adapting his guns by boring the chambers all the way through so that they could handle the .58-caliber rimfire cartridge.

- RELATED STORY: 8 Rimfire Replicas of History’s Greatest Battle Weapons

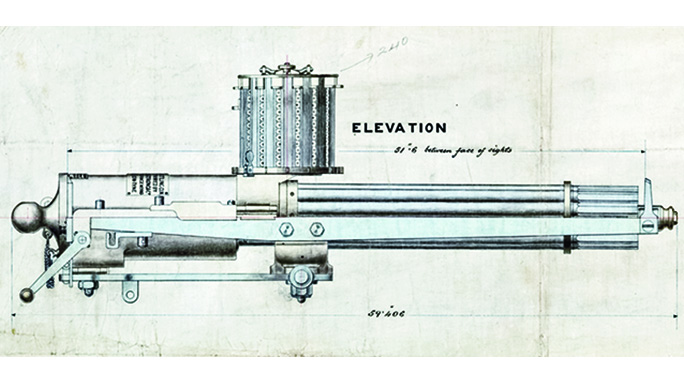

Gatling needed to redesign his gun so that it could handle metallic cartridges directly with the chambers formed in the breech of the barrel. This made the gun much more mechanically complex, requiring a system that allowed the cartridges to drop into a rotating carrier block and be pushed forward into the barrel chamber, fire them and then extract the empty cases. The “locks” had to reciprocate, moving backwards and forwards while the barrel assembly revolved. Gatling achieved this by creating a spiral cam track inside the lock casing that engaged with a “spur” on the tail of the lock body. This new mechanism was covered by new patents in 1865.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

This new Gatling gun contained all the mechanical elements that were to see it through until its demise in the early years of the 20th century. One of these refinements was a means of allowing individual “locks” to be removed in the event of failure or damage, allowing a gun to continue firing. This important and valuable feature alone distinguished the Gatling gun from all other manually operated machine guns.

Feeding The Beast

What did change quite dramatically over the four decades of the Gatling gun’s life were the cartridge feed systems. The earliest were simple tinned sheet-iron boxes for transporting the cartridges ready for use and which, with the lid removed, were inserted into the gun’s feed hopper where the cartridges dropped into the mechanism under gravity. This was modified soon after by creating a retaining flap held closed by a spring catch, and feed boxes of this type are usually referred to as the 1871 pattern.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

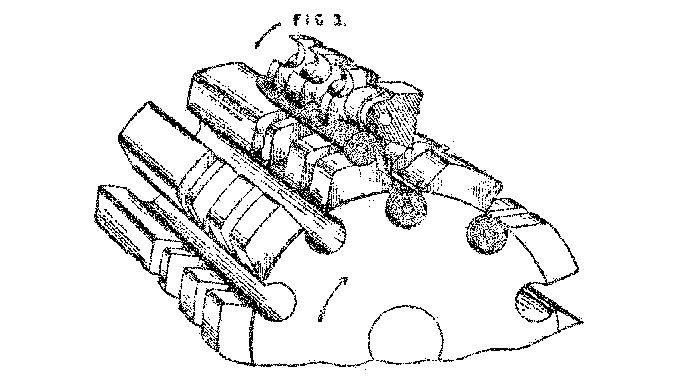

These boxes had limited capacities, and in 1870, Lewis Broadwell patented his drum magazine, which held far more cartridges and allowed for more continuous fire. It is a feature seen on many Gatlings illustrated in the 1870s. Inside the drum, separate compartments held columns of cartridges that were manually aligned in turn over the opening in the drum mounting platform, allowing cartridges to be fed by gravity, assisted by a weighted “follower.”

- RELATED STORY: Warhorse Legacy – A History of the 1911 Handgun

However, perhaps the most successful feed system was that patented by Lucien Bruce in 1881. The “Bruce feed” provided an effective system that could be loaded easily and could be kept topped up while the gun was still in use. The Bruce feed is the system featured on the guns that gave such vital service in the Spanish-American War.

All of these feed systems relied on gravity, and while the gun was relatively level, they worked without too much trouble. However, if the gun was elevated or depressed to any marked degree, the feed systems were likely to malfunction. This was overcome by the system patented by James G. Accles. The magazine looked like a square-cornered bronze doughnut with a carrying handle and held 104 of the .45-70 cartridges. Inside was a spiral track like the one in the drum magazines of Thompson submachine guns. The cartridges were pushed along this spiral track and into the gun by a “driver” geared to the rotating barrel cluster. This allowed the gun to function at extreme angles of depression and elevation, as shown in contemporary advertising. It was a sound idea, but the drums were easily damaged in the rigours of military service, so they were not wholly successful.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Despite the Gatling gun’s survival to serve in the Spanish-American War alongside the Browning Model 1895 machine gun, it had effectively been made obsolete by Hiram Maxim’s patent of 1883. Maxim’s revolutionary design utilized the energy of recoil generated by a fired cartridge to drive the mechanical cycle of feeding a cartridge, firing it and extracting the empty case. This fundamental principle set the pattern for a whole new avenue of firearms development that is still with us today.

- RELATED STORY: The Trojan Horse – The Original Spec Ops Mission

In the face of Maxim’s development, at least two attempts were made to devise means of making the Gatling’s operation automatic to allow it to compete. In both, some of the explosion gases were vented through small apertures and the pressure of the jets used to drive the mechanism. If any of these guns were built, they seem never to have advanced beyond the experimental stage. The only really successful experiment for alternative operation was developed in 1890, when the U.S. Navy asked the Crocker-Wheeler Electric Motor Company of New York to fit an electric motor to a Gatling fitted with an Accles feed system and a clutch that allowed to gun to be electrically or manually operated. Even geared down, the gun achieved a rate of fire of 1,500 rounds per minute! But who needed such an elegant way for the wholesale disposal of ammunition?

The Gatling gun was laid to rest in the early years of the 20th century, but the advent of jet aircraft and rocket-propelled missiles in the latter stages of World War II highlighted the need for guns with a greater volume of fire than the then-conventional machine gun could provide. Someone remembered those experiments of the 1890s, and 60 years later the genius of Richard Jordan Gatling enabled the creation of probably the most effective small weapons systems of the present day. Today’s Vulcans and miniguns are devastating in their effect, whatever the target. With modern fire control and aiming systems, bringing down rockets and high-speed aircraft is a task the modern descendants of the Gatling gun, with their focused and concentrated firepower, can do with ease.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

This article was originally published in ‘Military Surplus’ #188. For information on how to subscribe, please email subscriptions@