The Allies boasted a wealth of military talent, but the task of coordinating such a disparate group of personalities from such a diverse array of cultures was one of the greatest challenges facing the civilian leaders of their respective nations.

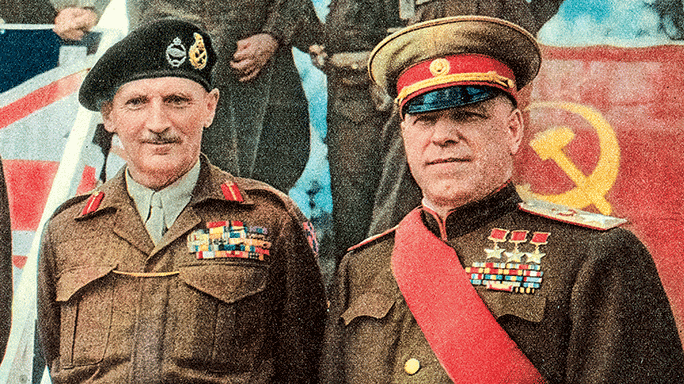

Bernard Law Montgomery, the black-beret-wearing British field marshal known as Monty, inspired his men by appearing on the front lines, but he irritated U.S. Gen. George Patton and other Allied commanders with his excess of caution and a sometimes boastful air. During the war, Monty commanded troops in France before escaping through Dunkirk; Africa, where he routed Erwin Rommel and earned the first Allied victory of the war; Sicily, where he raced Patton for bragging rights to prized conquests; and Italy, where he complained about strategic muddle. Montgomery was then given command of all ground forces assigned to Normandy following D-Day. But his caution in taking Caen drew the wrath of Patton, who once called Monty a “tired little fart.” Dwight Eisenhower took over Ground Forces Command in September 1944, leaving Montgomery and the 21st Army Group to fight several key battles in France and Germany. In his memoirs, he accused Eisenhower of prolonging the war through poor leadership, a charge that effectively ended their friendship.

- RELATED STORY: D-Day: June 6, 1944—Allies Invade Normandy

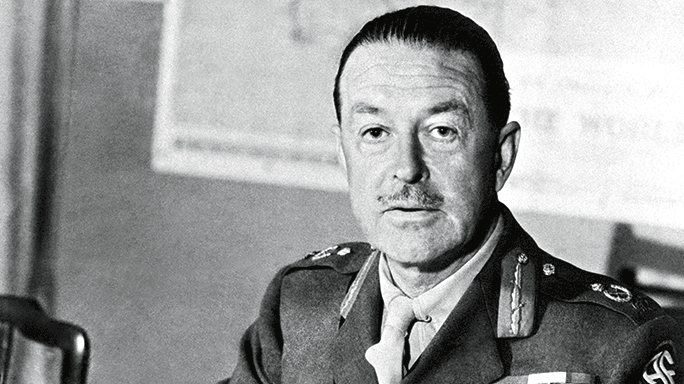

Field Marshal Harold Alexander was the measured and calm member of the Allied leadership bunch. Following WWI, in which Alexander fought on the Western Front, Rudyard Kipling wrote, “Colonel Alexander had the gift of handling men…. His subordinates loved him.” He remained in the military between wars, and when Great Britain entered WWII he commanded the First Infantry Division in France and was one of the last to leave the beaches in the evacuation of Dunkirk. He oversaw the retreat from Burma following the Japanese invasion, then was named Commander in Chief of the Middle East Command, overseeing the African campaign. U.S. Gen. Omar Bradley credited Alexander with helping inexperienced U.S. troops “mature and eventually come of age.” Following the Axis loss in Tunisia and the surrender of 230,000 Axis soldiers, Alexander was placed in command of Montgomery’s Eighth Army and Patton’s Seventh Army in the invasion of Sicily, and he remained in command for most of the Italian campaign. Because of his reserve and urbane manner, some officers considered Alexander to be empty of ideas, and Eisenhower chose Montgomery to lead ground forces following D-Day because of objections to Alexander’s style. As Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces Headquarters, Alexander accepted the German surrender in Italy on April 29, 1945. He retired from the military following the war and was named Governor General of Canada.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

- RELATED STORY: The Higgins Boat: How World War II Was Won

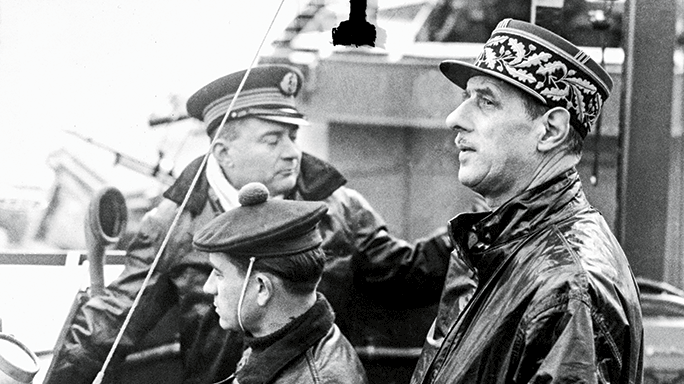

Few military or political leaders in history have been simultaneously as divisive and as unifying as Charles de Gaulle, the French general and statesman. He developed his military chops as a platoon commander in WWI, where he was wounded twice and captured at the Battle of Verdun. He was leading a tank brigade when WWII broke out, but he fled from France to England when Field Marshal Philippe Petain, the head of the new Vichy government, signed an armistice with Germany. With the support of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, de Gaulle formed the Free French Forces and broadcast a message across the English Channel urging the French people to resist the occupiers. De Gaulle was a difficult ally for Churchill and U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, thanks to a combination of his arrogance, fierce nationalism, and strong sense of mission. Churchill tried to remove him as head of the French resistance, while FDR refused to recognize de Gaulle’s provisional government until 1944. De Gaulle moved his headquarters to Algiers in 1943 so he could direct the provisional government on French soil. By agreement with Eisenhower, French troops were the first to enter Paris to finish off the Germans, and de Gaulle, viewed as the liberator, was greeted as a national hero. De Gaulle became president of France’s Fourth Republic, though due to his spat with Allied leaders he was not invited to participate in the summit conferences in Yalta and Potsdam. He never forgave Roosevelt, Churchill, or Stalin for the slight.

- RELATED STORY: A Salute To the Fallen: The 70th Anniversary of D-Day

Georgy Zhukov, born to a peasant family and destined to be a furrier, entered the military instead and would become the most decorated officer in Soviet history, earning the Hero of the Soviet Union four times and the Order of Victory twice. Zhukov oversaw the defense of Leningrad in September 1941, saved Moscow in October 1941, and in August 1942 was charged with the defense of Stalingrad. Later, when he led Soviet forces in the attack on Berlin, he was known as the man who did not lose a battle. In preparing for that final push to finish off the Axis powers, Zhukov urged his troops to “remember our brothers and sisters, our mothers and fathers, our wives and children tortured to death by Germans… we shall exact a brutal revenge for everything.” The resulting march by the Soviets was marked by rampant looting, burning, and rape. Following the war, Zhukov was named commander of the Soviet Occupation Zone in Germany and tried to provide an adequate standard of living for the Germans living there. By 1946, however, Zhukov’s popularity was viewed as a threat to Stalin, and he was stripped of all titles and tasks. His career was revived after Nikita Khrushchev rose to power, and he was promoted to Minister of Defense before being forced into retirement at 62.

This article was originally published in the WORLD WAR II VICTORY™ 2015 issue. Subscription is available in print and digital editions here.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below