Perhaps enough time has passed and enough wounds have healed in the last four decades to permit a scholarly summary and even a base appreciation of the simple small arms manufactured and used by the Viet Cong against our forces during the Vietnam War.

- RELATED STORY: 6 Must-See Vehicles at the American Military Museum

The French had been involved in Indochina as early as the 17th century and, after a brief war with China, consolidated the area as a French colony in 1883. Small groups of locals rebelled from time to time, but the French managed to hold on until World War II, when the Japanese invaded and then forced concessions from pro-Axis Vichy France. The Japanese were brutal occupiers. In response, anti-colonial Nationalists such as Ho Chi Minh and his followers consolidated the various resistance groups, Catholics, business owners, Communists and farmers into the Viet Minh.

The Vietnamese were somewhat effective in harassing the Japanese and what remained of the Vichy French, armed with a motley assortment of local crossbows, spears, muskets, shotguns and whatever arms they could steal or capture. Support and some small arms from the United States’ OSS, the USSR and the Chinese Nationalists followed and the Viet Minh fought the Imperial Japanese Army until the end of the war in 1945. With the Japanese gone, Ho and the Viet Minh seized power and declared independence.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The French, still very much bruised by WWII however, wanted their colony back and the bloody First Indochina War ensued (known as the “Anti-French Resistance War” in contemporary Vietnam). By this time, the Viet Minh were better armed, having a mixture of French, U.S. and surrendered Japanese small arms, but there were still not enough to go around. Again, the Viet Minh used whatever they could manufacture locally. The French were heavily supplied with small arms from the U.S. and those it had captured from the Nazis or continued manufacturing in French-occupied Germany. Eventually, the country was divided at the 1954 Geneva Conference into the Communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north and the Republic of Vietnam in the south, as the French withdrew.

Members of the Viet Minh were left behind in the south to organize an insurgency and immediately began agitating and undermining the pro-Western government. The situation on the ground and subsequent escalation of U.S. intervention of course evolved into the Vietnam War.

Primitive Weapons

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

From a small arms standpoint, between about 1954 to 1963 the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) was fairly well equipped, with the assortment of foreign arms already discussed, as well as regular shipments of arms from China after 1949. The NVA cadre and Viet Minh in the south—which became officially known as the National Liberation Front for South Vietnam, and colloquially known as the “VC” or Viet Cong (“Viet Cong” is a contraction of sorts of the term “Vietnamese Communist”)—were cut off from their main source of supplies north of the DMZ. Once more, they had to make do with what could be bought on the black market (often paid for by the sale of opium), smuggled in on the unreliable Ho Chi Minh Trail, or made locally. Needless to say, standardization in VC units was non-existent.

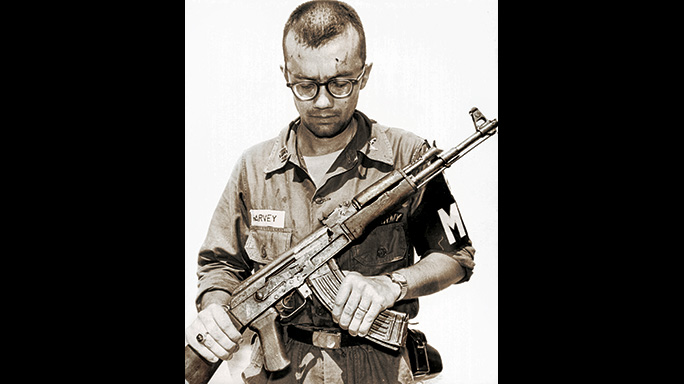

Generally, the lower the unit was in the VC organization, the more primitive the weapons. Main force, HQ and regional units were better equipped. Early on, these types of units had a fair amount of French weapons, ex-German Wehrmacht (in some cases passed along from the USSR) K98s, MP40s and MG34s and, as the insurgency went on, more and more Soviet M44s, Chinese Type 53 carbines, SKSs and eventually AK-47 rifles.

A local VC militia on the other hand might have none or only a few modern weapons. To compensate, villages and hamlets were protected by a system of early-warning observers, entry and exit points booby trapped with Punji-stick-filled pits or grenades attached to tripwires, traditionally made spears and crossbows as well as crude, locally made pistols and long arms. VC cadre often set quotas, and villagers, including schoolchildren, were required to make so many Punji sticks, improvised explosives, crossbows or primitive firearms per day.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

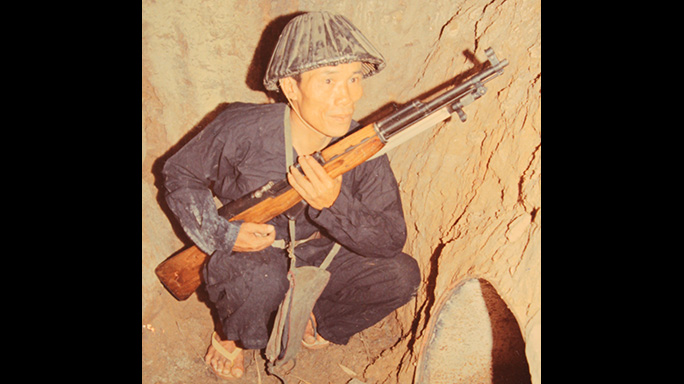

Workshops for the manufacture of firearms varied greatly. It may have been a single hut in a village or a well-camouflaged facility deep in the jungle. VC workers used simple hand tools to shape metal components and wood stocks. More sophisticated workshops with more skilled labor existed deep inside the vast array of tunnel complexes constructed by the VC in South Vietnam, especially in and around Cu Chi in the so-called “Iron Triangle.”

Improvised Hardware

The VC used whatever materials they could scrounge—pipe, wire, old hinges, door lock mechanisms, metal bands, copper, brass, spent ordnance, scraps of steel or aluminum from downed aircraft, nails for firing pins, etc. Broken or incomplete firearms were repurposed or rechambered for whatever ammunition was most readily obtainable. Tolerances were poor and proper metallurgy non-existent on the majority of weapons produced locally, and the rifling of barrels was far beyond the skill of most VC weapons makers. Type and complexity ranged from single-shot, slam-fire pistols and rifles made from smooth water pipe, barely capable of firing a few shots before falling apart, to rather complicated and functional copies of more modern designs. Of course, whenever possible, the cruder weapon would be used to kill their enemies with the hope of obtaining a more modern weapon.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Of note, concerning even the most primitive and barely functional examples, the author has observed a seemingly concerted effort to make jungle-made weapons appear to be more formidable than they actually were. Bolt-action shotguns made from pipe for instance, housed in a stock that looked outwardly similar to the M1 Garand. Others include simple spring-action repeaters that mimic the M1 carbine, broken SKSs repurposed to look like an AK, and crude pistols made to look like the 1911A1. The list goes on and on. The probable rationale behind this was, at least from a distance, a U.S. or Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) unit might actually assess that a given VC unit might be better armed than it actually was. Or perhaps it was simply that the VC copied whatever more modern weapon they had on hand, which was most likely one of U.S. design.

From 1963 to 1965, the North was managing to sneak whole NVA regiments into the south. U.S. and ARVN forces were unable to effectively stop the flow of munitions and weapons on the Ho Chi Minh trail and traffic had picked up enough to begin equipping even the lowest-echelon VC units with more modern Soviet and Chinese weaponry. The most commonly encountered weapons were the Chinese Type 53 carbine, the SKS, the AK-47 and the North Vietnamese-produced K-50 submachine gun. This enabled the insurgents to graduate from propaganda actions, defensive or brief harassment engagements to larger coordinated offensive operations against the government of the South and U.S. forces.

In 1968, the VC left its hamlets and tunnels and mounted its most famous campaign, the Tet Offensive, which targeted over 100 urban centers in the south, to include the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. Bold but militarily unsuccessful, Tet decimated the rank and file of the VC, forcing the North to fill one-third of the Viet Cong units with NVA regulars.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

- RELATED STORY: Tactical Trucks: Top 15 All-Terrain War-Zone Wheels

By about 1970, the Viet Cong inventory was fairly standardized with CHICOM small arms down to the village level. Jungle workshop and homemade small arms were regularly encountered by U.S. forces and its allies up until the mid-1960s, and only sporadically thereafter. Captured examples were studied and sent back to facilities in the U.S. and nearly every military museum in the U.S. has an example or two in their collections. Many more were captured by servicemen and sent home as souvenirs, and these turn up from time to time on the market or at shows. Though crude and largely unsafe to fire, they are important pieces of firearms history, representing what can be produced with scant materials and little know-how as well as the extremes that humans will go to in times of war and adversity.

Author’s Note: The author wishes to thank the staff of the United States Navy Museum, Washington Navy Yard, Washington D.C., the United States Naval Academy Museum, the United States National Archives and Records Administration, the United States Army, the U.S. Army Ordnance Museum, the United States Marine Corps Museum, the NRA’s National Firearms Museum, the over 3.4 million U.S. military veterans who fought, toiled and bled in Southeast Asia and the many service members who lost their lives in an attempt to stop Communist aggression and defend the civilians in the Republic of South Vietnam.