Story written by Frank Barclay with Lamar Underwood:

When we first stepped through the door of the hanger, the sight before us slammed into our senses like some huge unworldly apparition. My wife, Betty, and I were standing before a smoothly shaped, curved cloud of light-blue texture. I blinked. “No,” my aging eyes told me, the “cloud” was dark blue. No, it was pale gray. Whatever color it was, the mysterious object seemed so alien to anything we had ever seen that it certainly did not belong here, not in this building that sat innocently in the pleasant Missouri countryside. There was something that seemed almost God-like about the structure, as if it could not have been created by the hands of man.

- RELATED: Classic Aircraft: Top 12 World War II Dogfighters

- RELATED: Great American War Helmets Of World War I

As we watched, taking in this amazing vision, panels swung down from the bottom of the enormous “cloud,” opening its great belly. We were invited to step forward and a moment later we were staring up into the operations center of America’s most secret, most effective and costly bomber every produced. The Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit, known throughout the world as the Stealth Bomber.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Betty and I were in a unique situation that day in 2013. Civilians, no matter how powerful or famous, are never permitted to stand where we were in the B-2 hanger, able to actually reach out and touch the aircraft’s skin, to peer into the amazingly complex aircraft interior. Our security clearance came directly from U.S. Air Force and the commander of Whiteman Air Force Base, home of 19 B-2 bombers, each housed in its own environmentally controlled hanger. A 20th B-2 is stationed at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The planes comprise America’s 509th Bomb Wing.

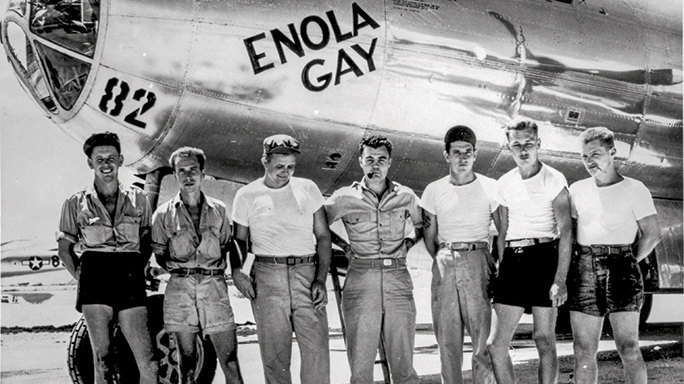

My association with the original 509th was what had brought us here as guests on this amazing visit. The welcome began when our host, Colonel Rick Milligan, picked us up at our Missouri home and brought us to the base. At the Whiteman gate, we posed for a photo beneath the actual B-29 bomber named “The Great Artiste,” which flew with the Enola Gay in the Hiroshima atomic bomb attack. It’s a plane with a history tied to its unit, the 509th Bomb Group Composite, which is made up of the B-29s, the pilots and crews who flew them great distances in dangerous bombing raids on Japan in World War II. Their achievements are now part of military history.

These achievements are also chronicled in my own 93 years of memory. For, although I have forgotten much in those years and, with the greatest sadness I have ever known, lost my beloved wife of 70 years earlier this year, my chest of great memories is very rich.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As a survivor of very special Air Force history, I was very moved to be invited to Whiteman, and thrilled to the core when the Colonel presented me with a new pair of wings to replace those I had lost. I had once worn them proudly, and I had flown with the B-29 heroes of the 509th who brought Japan to the surrender table.

Elite Training

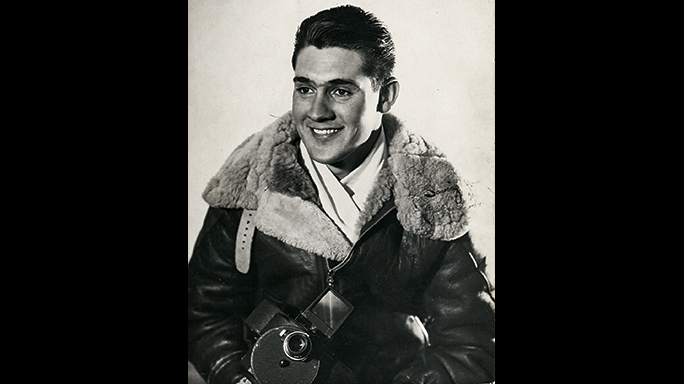

I came to the U.S. Army Air Corps (later called the Air Force) as a raw young man who already had a professional interest in photography, and a tremendous interest in flying—because it sure beat marching. Newsreels in movie theaters (that’s how we got videos in the pre-television eras) had convinced me that the fate of being drafted and put into the foot-slogging, pack-carrying infantry was not for me. One of my best friends had been killed in a light-plane crash right in front of me at a local airport, but that did not change my view that flying in the U.S. Army Air Corps beat blisters and bullets

in the infantry.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I was told that enlistees sometimes had their choice of branch of service, so I signed up, hoping to get into aerial photography. I had a mentor at the local newspaper who had guided me through training with a Speed Graphic camera. I loved my job on the paper, but with the draft staring me in the face, I decided on enlisting and taking my chances on getting into the Air Corps.

All this history was very much on my mind last year when Betty and I stood there in the B-2 hanger at Whiteman gazing up at this amazing airplane that had a crew of two and delivered more firepower over greater distances and much higher altitudes than entire fleets of previous bombers.

At that moment, I could not help thinking about pigeons. Yes, amazingly enough, pigeons! They were my first troops, my first command. Handling pigeons was my first job in the Air Force.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

These weren’t ordinary city park pigeons. They were homing pigeons, also called carrier or messenger pigeons. This remarkable bird has the innate, mysterious ability to return to its nest or coop from virtually any location where it is released. Flights of over 1,000 miles have been documented, and races are popular with pigeon owners. Our Air Force pigeons were donated by private owners, including celebrities like Roy Rogers and Andy Devine. These birds were distant relatives of numerous heroic pigeons of World War I, such as the bird called “Cher Ami,” awarded the French Croix de Guerre for delivering 12 important messages despite being wounded.

The Air Force had launched an experimental program to see if homing pigeons could be used as messengers from planes forced down or shot down. Could the pigeons fly back to base carrying a message on the stricken plane’s location and condition? Helping answer that question was my duty for months in 1943 as a corporal at Kern County Airport, near Bakersfield, California.

I came there from training to be an aerial photographer at Lowry Field in Denver, where we flew mostly in B-17s, the “Flying Fortress” bombers. Then I had started training to become a pilot at Luke Field, Phoenix. I left Luke, not as a “washout,” but because I had been selected as one of 20 finalists in an Air Force program to train personnel for advancement to eventual general officer rank. We were to attend top civilian colleges on special assignment. My orders to report to Stanford University, in Palo Alto, California, in September came through in the spring and with them an assignment to spend the summer with the homing pigeons.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Like old Army units that had to stable and train horses, our unit worked with pigeons. The birds had coops and were fed and watched over by myself and the 171 men and 11 officers comprising our unit. In our mission, we experimented with actually releasing the birds from planes. The results were not good—torn-up feathers, battered bodies. In looking for alternate methods we came up with constructing boxes that could carry the birds so they might survive a crash. We loved those birds, took care of them with zeal and knew each one by name.

I left the program eventually, but not for Stanford as things turned out. In one of those life-changing decisions, with an airplane sitting on the ramp to take me to Palo Alto, I resigned my new commission and assignment. I wanted to stay where I was, happy with my friends and duties and the base itself. Deep down, I decided I didn’t care about promotions, staying in the Air Force the rest of my life.

The Air Force, surprisingly enough, didn’t act furiously, didn’t bust me back to private. Eventually, I was given orders for a new assignment, a replacement depot in Salt Lake City. I soon found myself among a bunch of pilots and bombardiers, all officers. Something was up.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

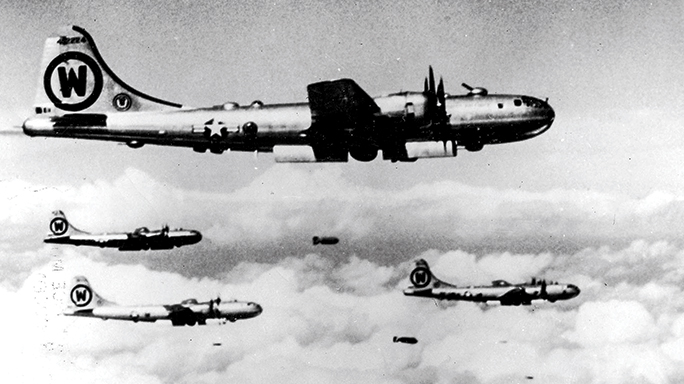

That “something” began to come clear in a dramatic way at dawn three weeks later, when I gazed out a train window as we rounded a curve in Great Bend, Kansas. Dramatic in the early morning light, huge airplane rudders soared against the sky in rows. The tail structures belonged to B-29s, the Air Force’s new “Super-fortress,” the bomber replacing the B-17s.

The B-29 was capable of reaching altitudes around 40,000 feet (far above the B-17’s bomb-load limits, where it could be downed by ground artillery fire) and carrying huge payloads thousands of miles. Seen in full on the ramp, while my mind compared the Superfortress to the B-17s I had flown in so often during my training, the B-29 left me awe-stricken. Here was an airplane of such sleek design and size that surely it would rule the skies. This was the airplane that would eventually write the final chapter in the aviation war against Japan.

Top Secret

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

My “Superfortress” duties in aerial photography at Great Bend got off to a riveting start when I was issued a small blue card that stated that Corporal Frank Barclay “has duties which require his presence in The Restricted Area.”

(Today, that small blue card counts as one of my most prized possessions. There are so few survivors of that time that I was included in invitations to participate in ceremonies commemorating the B-29 at the Smithsonian Air-Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The “blue card” even plays a bit part in the movie Above and Beyond chronicling the Enola Gay and its captain, Paul Tibbets.)

Now my training as an aerial photographer put me on duty as the only enlisted man in a five-man office where we scored the bomb drops of bombardiers training with B-29s. Sitting at a light table, I could study the film made through the Norden bombsight and score the accuracy within inches. The 100-pound smoke bombs created a dot in the film, even at altitudes above 30,000 feet. I even recall one drop at 46,000 feet. The target was a 100-foot circle on the ground, and in the center a stack of old boards was placed in a pyramid shape. Hitting that stack was called a “shack,” an expression that survived into modern Air Force eras.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Camera bombing, simulating actual bomb drops, was also part of the training. A favorite target, 250 miles away, was Union Depot in Kansas City, where rail lines converged in visual splendor through the Norden bombsight.

It was on some of these missions that I got in actual flying time (earning my “Flight Pay”) working with the bombardiers in a different B-29 every flight. These crews, and the airplanes themselves in many cases, went on to the Pacific to fly in raids on Japan.

Colonel Paul Tibbets, destined to fly the B-29 he named “Enola Gay” (after his mother) in the Hiroshima atomic bomb attack, had an enormous presence at Great Bend. He was seldom seen, but operating a project with the code name “Silverplate,” he carried more clout than perhaps any other Air Force officer. No one knew exactly what Tibbets was up to—all kinds of rumors were swirling about—but we all knew it was big. Real big.

Tibbets had flown some of the early and most important B-17 missions bombing Germany and was known to be a skilled and demanding commander. What we did not know was that he was working directly with General Leslie Groves, head of the secretive Manhattan Project, to develop a plan for delivery of the atomic bomb. Colonel Tibbets had been hand-picked to form a special B-29 group to bomb the island of Japan.

I met him once, during one of his visits to Great Bend. I was summoned to Tibbets’ office, and I went in, kind of trembling, thinking, “What have I done now?” The meeting, however, was cordial and pleasant. Accompanying Tibbets was a gentleman whose daughter I had been dating quite seriously the year before. He had me summoned just to say hello. I learned later that he was a base air inspector. I can’t remember anything special about Tibbets, except that he seemed just like all the other pilots I knew—confident, friendly and very sharp.

Air Emergency

Working with all the B-29 training bases, and bringing in some of his crew members from the B-17 German raids, Tibbets eventually assembled what was called the 509th Composite Group. It went into training at Wendover Field, Utah, and eventually shipped out to our B-29 base at Tinian. They were flying modified B-29 aircraft with special bomb bays. Rumors were rampant. But they were only that, rumors.

I didn’t make it to Tinian with Tibbets and the 509th. I like to think that I would have been chosen to ship out with the group, except for one flight. A flight to Cuba.

We had some B-29s stationed at Batista Field, Cuba, training with simulated radar bombing from high altitudes. Our groups at Great Bend also began training there. We flew our B-29s from Great Bend to Cuba during the night, radar-bombed the target, then flew home. Nonstop. Almost exactly the same distance as flights from Tinian to Japan.

It was on one such mission, just at pre-dawn on our return trip, that we had a fire in our Number Three engine. (That’s the first one on the right, next to the fuselage; the B-29 was plagued with engine problems for years.) I was sitting in my usual spot on a pile of parachutes, and by the time the captain ordered us to bail out, I was ready with my chute and Mae West jacket. I went out the bomb bay.

I don’t remember much after that, except the shock of hitting the water and being so cold. Cold and scared—I had never learned to swim. The Mae West jacket did its job of keeping me afloat, and, miraculously, a patrol boat picked me up right away. We were somewhere near Biloxi, Mississippi, I later learned, and the pilot had evidently called in our position. He also kept the plane flying and only one other crewman had bailed out.

I spent some time in the hospital, but when I returned to duty, I faced another setback. I suddenly lost my ability to speak. I didn’t stutter. My diaphragm simply refused to work. I spent 52 days in the hospital before finally being released with what the doctors described as a “central nervous system condition.” They never pinpointed my malady as being connected to the parachute jump.

I was given a medical discharge. WWII was over for me. I went into journalism school at the University of Missouri. Six days later, the 509th dropped the first of two atomic bombs.

I’m thankful that I am still here at 93 to describe those days to you. The Air Corps lost over 200,000 in WWII. Only the infantry lost more. Much of those days has faded from my memory now. But every time I look at those wings given to me last year, to replace the ones I had lost, I remember what it was like to be young and full of purpose, flying high with the best aviators on earth in the Army Air Corps.

Editor’s Note: Frank Barclay is the retired owner of his own advertising agency. His career in advertising and journalism includes years as a lead newspaper photographer. He now lives in Missouri.