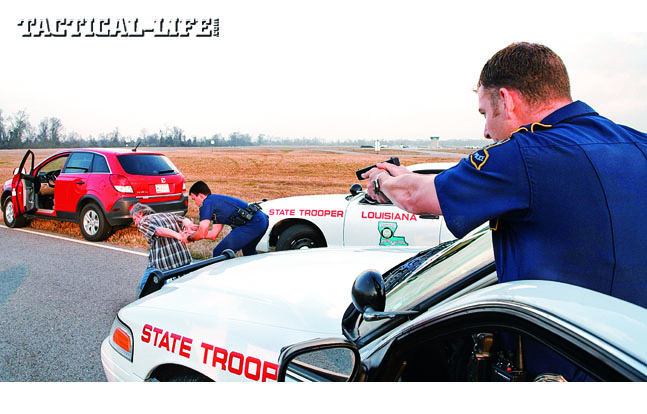

The importance of proper law enforcement handcuffing for officer safety remains a timely topic. Shortly before writing this, I viewed the in-car dashcam footage of a suspect allowed in the backseat of a patrol car with his hands in front of him. The camera caught him drawing and fumbling with a handgun the officers had missed in their search. One of the two officers up front sensed something wrong, sprang out the door and contained the situation when he drew his pistol and leveled it on the suspect. Yes, what I’ll call Case One could have turned out a whole lot worse, perhaps leaving two dead officers slumped in the front seat of the patrol car.

This time, though, we’ll talk about liability issues relating to handcuffing. That’s because some officers have become so fearful over the years about “excessive force” and “police brutality” complaints that they don’t properly handcuff their arrestees. It’s also because some, through carelessness or through anger, do handcuff improperly and actually cause unnecessary injuries. No professional law enforcement officer wants that.

Learning Restraint

Many years ago I debriefed the state trooper who, in Case Two, was arresting a prison escapee. The man complained that the handcuffs were too tight. The compassionate trooper unlocked the handcuffs to adjust them and was instantly and violently attacked by the suspect, who broke free. He gained control of the arresting officer’s .357. Before it was over, that good lawman had been shot in the arm with his own gun and crippled for life, and another trooper had to finally shoot and neutralize the would-be cop-killer.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

It is certainly possible for too-tight cuffs to cause nerve damage and create permanent injury by cutting off circulation if left in place long enough. Each such allegation is weighed in court on its merits and, as the law and the Supreme Court’s long-standing Graham v. Connor standard require, “within the totality of the circumstances.” For Case Three, we’ll look at part of the ruling in April 2007’s Freeman v. Gore: “Arrestee’s excessive force claim, based on an allegation that her handcuffs were applied too tightly, was not meritorious when her only injury was bruises on her wrists and arms. Leaving her in a patrol car for 30 to 45 minutes with tight handcuffs is not excessive force.”

My friend Laura Scarry, an ex-cop, is one of the nation’s top attorneys working to defend officers and departments from baseless litigation. She’s the lawyer I’d retain if I stood so accused on her turf, the Chicago area. In her article “Tight Handcuffs” in the police professional journal Law Officer (Volume 3, Issue 12), Scarry wrote of Sleeman v. Oakland County (Case Four for our purposes), in which the verdict went against the officers because there were provable injuries and, particularly, because the officers had ignored the suspect’s complaints about the too tight handcuffs.

However, she also notes that some courts have ruled in favor of the officers in “too-tight handcuff” complaints when there was no provable damage, or when it was clear that the police had made reasonable efforts within the totality of the circumstances to assure that the handcuffs were not applied wrongfully, maliciously or negligently and had responded to the arrestees’ complaints that the bracelets were too tight. These decisions include but are not limited to Case Five, Bastien v. Goddard; Case Six, Glenn v. City of Tyler; Case Seven, Foster v. Metropolitan Airports Commission; and Case Eight, Carter v. Morris.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Training Takeaways

Listen to complaints about too-tight handcuffs. Paying attention to your own safety, examine the handcuffs and their wrists. If you decide that you do indeed need to loosen them, make sure the suspect is restrained and can’t break away during that process. Remember Case Two! In addition to going for your gun, the suspect can also use the cuffs themselves as a weapon.

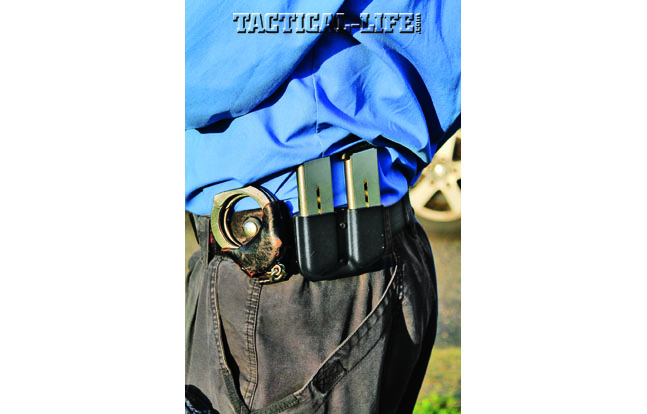

As a general rule, if you can insert the tip of your pinky finger between the handcuff and the suspect’s wrist, it’s unlikely to be too tight. Maintain control of his balance, and at least one and preferably both of his hands while you’re performing this test!

Always double-lock the cuffs so they can’t close any further than you have carefully closed them. Sometimes, they can get tighter when a drunk just wiggles around in the back of the patrol car. Sometimes, suspects will tighten their own handcuffs down and turn their hands into swollen blood-bags in hopes of getting a “courtroom payday” with an excessive force allegation. Double-locking prevents this.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Stay safe. Always remember that you do have a responsibility for the arrestee’s well-being, but you have the same responsibility for yourself and for others he might harm.

Check out this author’s article on Tactics For Surviving an Ambush Attack on Police.