All military personnel need a primary weapon, no matter their primary specialty. In 1938, there was an unavoidable punch-up looming between America and the Axis powers—we had a miniscule standing army at the time. Millions of hastily trained American troops would soon be pressed into service, troops who did not yet have weapons. The bulk of these soldiers would not serve as infantry, but they would soon all be duking it out in the hedgerows of Europe, in the jungles of the Pacific and, for all we knew at the time, on Main Street, U.S.A.

Although wildly successful as a short-range manstopper, the M1911 pistol did share the handgun’s inherent weakness: Its effective range was limited by its cartridge, non-adjustable sights, short sighting radius, and the dearth of combat training. With no aspersions on the worthiness of the .45 pistol, it was apparent there were millions of support troops who would become full combatants. They needed weapons that were more combat-effective and could be constantly carried while they performed their primary duties.

Why A Carbine

In 1938, the chief of infantry expressed interest in a “light rifle” or carbine, for non-infantry troops, noncoms and officers as an alternative to the M1911 pistol. “Carbine” traditionally meant a scaled-down rifle, like the trapdoor Springfield cavalry carbine or the Krag carbine the Rough Riders had when they stormed San Juan Hill. But what was stipulated in the mission essential needs statement (MENS) approved in 1940 and the exemplars submitted for tests in 1941 were a new animal: tactically, this carbine was not a scaled-down rifle but an enhanced-ability weapon designed to have better range and lethality than the pistol. It could function as a submachine gun but with greater range and accuracy, a lighter but more lethal cartridge, and less overall weight.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

From concept and MENS to its cartridge and the actual fielding of this new weapon, the Auto-Ordnance M1 Carbine was the first of the genre now known as personal-defense weapons. The design and performance parameters of the initial requests came close to—but fell short of—the classic definition of an “assault rifle”: shoulder-fired, detachable box magazine, selective fire, reduced-power round. The historical difference was that an assault rifle fires a reduced-power rifle round, while the U.S. Auto-Ordnance M1 Carbine was chambered for a round that was essentially a more-powerful pistol cartridge. Further, the assault rifle was designed to serve as a first-line infantry weapon. The M1 Carbine was intended as a more-effective defense weapon.

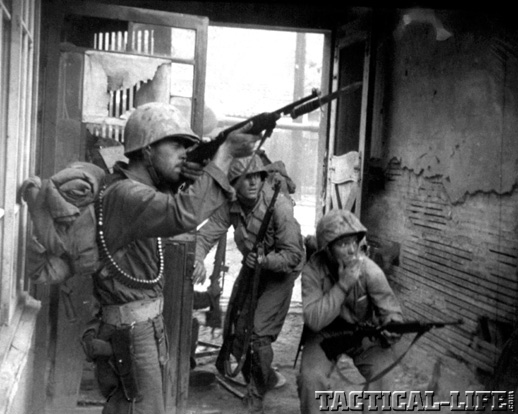

Because the ubiquitous Carbine proved so popular, it was occasionally employed as a battle rifle where the relative weakness of the cartridge was balanced by the fact that there were 15 (and later, 30) rounds. There are always tradeoffs, however, and the cartridge did not have great penetrating ability—a problem in jungle warfare and a problem in Korea when shooting through layered winter clothing. The Carbine’s shorter range was less of a factor, as it was designed to replace the pistol—it only fell short when it was used (optimistically) to replace the rifle.

The Carbine served well for its intended purpose alongside the venerable and more powerful Garand, until they were both retired in favor of the M14 starting in the late 1950s. The Carbines and Garands were sold for civilian shooting matches through the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP) and then as surplus on the commercial and police markets. Genuine pieces of living history, these handy small arms were commercially produced in various iterations and are still in production today as GI clones, by Auto-Ordnance, a division of Kahr. New loadings have upgraded this rifle’s ability as a home-defense, police and hunting weapon. It is one of the most interesting WWII ordnance developments.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Engineering A New Species

The development, production, fielding and combat use of the Auto-Ordnance M1 Carbine is one of the few examples in history where an ad-hoc committee accepted and implemented a new firearm design that was then skillfully and expeditiously built by an ad-hoc manufacturing group of jukebox, typewriter, automobile and postal-meter builders. This remarkable feat was accomplished when our nation was at the short end of the lever, in a war it was unprepared for—a textbook study in what mission focus can accomplish. Bureaucrats subjugated their passion for paperwork and bean counting, designers set aside personal pride, and industry worked among itself, swapping information and even parts without paperwork to keep those Carbines rolling off the assembly lines.

This new weapon started with a new cartridge specification based on a rimless version of the .32 Win self-loading round. It had a round-nose 110-grain bullet exiting an 18-inch barrel at approximately 1,970 feet per second (fps). It was a significant upgrade over a pistol, with a maximum effective range of 300 yards—although, at that range, its ballistics were about equivalent to a .32 ACP round. The Auto-Ordnance M1 Carbine was the first American cartridge exclusively issued with non-corrosive primers.

This project accelerated through the design, acceptance, production and deployment processes at dizzying speed. Sample designs were submitted by Savage, Woodhull Corporation, Colt, Harrington & Richardson (Reising design), Springfield Armory, Bendix Aviation (Hyde), and an individual named Russel J. Turner, as well as Winchester, almost as an afterthought. By September 3, 1941, infantry trials showed that Winchester was the clear winner.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The various design components incorporated in the Winchester M1 Carbine came together in what could only be regarded as an odd twist of fate. Winchester had not planned a submission, as it was already involved in a military rifle project by Ed Browning, John Browning’s brother. Following Ed’s death, Winchester engaged David M. Williams, who incorporated his short-stroke gas piston into the .30 Carbine. When Winchester showed this .30-06 design to Ordnance, Ordnance requested they scale the carbine down for tests. With partial cooperation from Williams, Winchester’s design team took Williams’ short-stroke gas piston, the Garand’s stock, bolt and operating rod and the M1905 Winchester rifle’s fire-control group and melded them into a working prototype. Army Ordnance selected this design, hands down.

By November 11, 1941, five exemplars by Winchester and five by Inland were submitted to Ordnance for testing. Less than a month later, on December 7 (Pearl Harbor Day), Ordnance had completed production drawings. On December 11, Germany and Italy declared war on the U.S.

Specified, Built, Upgraded

By June 1942, Inland was in production—by September, Winchester. By November 1942, Underwood and Rock-Ola started production, Inland was making the first folding-stock M1A1s, and M1 .30 Carbines had drawn first blood in North Africa.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Production soon followed by Quality Hardware, National Postal Meter, Standard Products, Saginaw Gear and IBM. The FN plant in liberated Belgium began converting M1s to M2s. As the war in Europe wound down, FN began a repair and rebuild contract. Winchester and Inland completed production, and Springfield Armory assumed the program. By June 1946, FN’s work was completed, and in 1967 Springfield Armory closed. Responsibility for Auto-Ordnance M1 Carbine parts acquisition passed to Army Materiel Command.

Tabulations vary, but an estimated number of around 6,110,000 Carbines had been built: 5,551,311 M1s, 140,000 M1A1s and 417,500 M2s. Many of the M1s were converted to the M2 configuration, and there was subsequent production of a few thousand M3 Sniperscope variants.

Original requirements stipulated selective fire, but the millions of semi-autos deployed shot more enemy than the full-auto models. Thus, the M1 model was semi-auto only, with engineered provisions for retrofitting full-auto kits. By the time a few million M1s had been fielded, minor mechanical considerations and user requests arose. When the M2 was being made or M1s retrofitted to M2 standards, there were other tweaks as well. By design, parts-interchangeability between models and manufacturers was a landmark testament to Eli Whitney’s original principle of parts standardization.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Readers may find references to “M2” bolts or “M2 barrel bands,” “M2 magazine catches” and so forth, which happened to be installed at the time of the M2 upgrades but had nothing to do with selective fire: They were simply the newer, improved parts that came along at the same time.

The M1 had no provision for a bayonet. GIs wanted one, so a new barrel band was designed with a bayonet lug for new M4 bayonets. The initial push-through safety could be confused with the magazine release (oops), so it was converted to a pivoting type. The magazine catch and matching notches on the magazine were increased from two to three. Magazine capacity was increased from 15 to 30. Rear sights were upgraded. It weighed 5.2 pounds empty.

The M1A1 featured a side-folding stock. All were made by Inland, and all were made in semi-auto, although, with the wood removed to accommodate the selector switch, they would accept the M2 field conversion kits. Following ordnance rebuilds, M1A1 stocks may be found on any manufacture. They weighed over 6 pounds but were 10 inches shorter folded.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The M2 had a stronger stock, internally relieved to accommodate selective-fire parts. As issued or rebuilt, M2s had a round bolt, a new mag-release assembly, a barrel band with a bayonet lug, a new safety and 30-round magazines. Upgrade parts aside, parts unique and necessary for selective fire included the selector switch, disconnector, disconnector lever, M2 sear, M2 slide, and M2 hammer. Under current U.S. law, these parts cannot be possessed if an individual owns a .30 Carbine. Conversions were made at the time of ordnance rebuilds or via T17/T18 field kits. It was slightly heaver than the M1 because of the round bolt, selective-fire parts and a heavier stock. A loaded 30-round magazine weighed slightly more than a pound.

The M3 was an M2 fitted with either an M1, M2 or M3 active-infrared night scope. Although a bulky unit, the M3 was credited by some sources with up to 30 percent of the enemy small-arms casualties on Okinawa.

Present Day

The Auto-Ordnance M1 Carbine went on to serve with American troops wherever they fought in WWII, Korea and Vietnam, until it was replaced by the M14 and M16. It has served with more than 60 nations, and as a tactical upgrade for a handgun, it served very well. It was not intended as a battle rifle, and when pressed into that role was at the limit of its range and ability. But as a home-defense, police, plinking or small-game rifle, it’s still hard to find anything handier than a little M1 Carbine.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Check out this article about WW2 & Auto-Ordnance Commemoratives!