The gun crime issue has generated an enormous amount of public attention over the last six months, and the ensuing debate over potential solutions has been both acrimonious and polarizing. While the discussion and debate continues on how best to deal with the larger issue of gun violence in our society, police must deal with its aftermath every day.

While the headlines rage and policy makers and social scientists debate solutions, our crime-fighters are being dispatched to investigate gun-related murders and assaults in countries throughout the world. Inside every police and media report of these shootings are real victims who deserve justice and armed criminals who will continue to do more harm until stopped by the police.

Improved efforts aimed at stopping armed criminals and bringing them to justice is one response to gun violence that seems to have universal support, and whether we want to admit or not, there is much more work that can be done in this area. The more effective we are at removing armed criminals from our communities, the safer we are in terms of our well-being and the freedoms we enjoy.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

National Solution

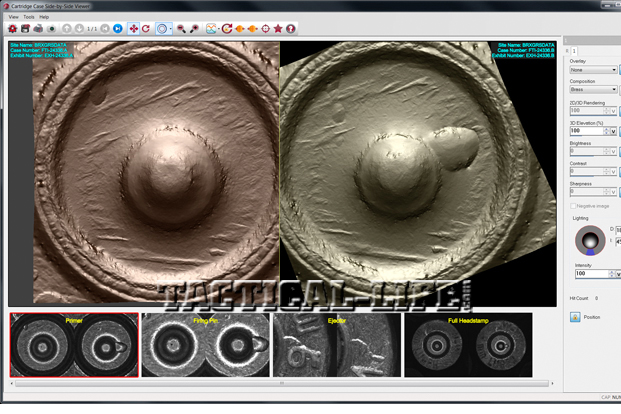

I recently saw an investigative report from WKYC-TV in Cleveland, Ohio, that really made me stop and think. The report addressed the amount of data submitted to the National Integrated Ballistics Information Network (NIBIN) by the police agencies in region. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATFE) administers the federally funded NIBIN program. In a “fact sheet” released this past February, the ATF indicates: “[NIBIN] Partners use Integrated Ballistic Identification Systems (IBIS) to acquire digital images of the markings made on fired ammunition recovered from a crime scene or a crime gun test-fire and then compare those images (in a matter of hours) against earlier NIBIN entries via electronic image comparison. By searching in an automated environment either locally, regionally or nationally, NIBIN partners are able to discover links between firearms-related violent crimes more quickly, including links that would never have been identified absent the technology.”

The field-proven fact is that, when properly managed, crime-fighting programs like the NIBIN help police be more effective at identifying and stopping armed criminals. The NIBIN is strongest in situations where law enforcement is often weakest—in situations where criminals are moving across multiple jurisdictions, committing crimes and scattering evidence along the way. Situations, for example, in which a weapon used in a Boston, Massachusetts, murder case can easily wind up in the police property room in Providence, Rhode Island, associated with an unlawful carrying incident. Without an NIBIN check, neither the police in Boston nor Providence would likely know of each other’s interest in that crime gun. The result: a murder case left unsolved.

Collecting Evidence

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The NIBIN only works when law enforcement feeds it. That is, when ballistics evidence collected from all crime scenes and test-fires discharged from all guns taken into police custody, pursuant to an investigation of criminal wrongdoing, are submitted for NIBIN processing.

I think that is what the reporter Tom Meyer and producer Rick Hepp of WKYC-TV were trying to get a handle on when they spent months poring over the logs of firearm-related evidence of a number of police agencies in northeastern Ohio. As unfortunate as it may be, from my experience, I do not find what the WKYC-TV news team found to be the least bit surprising: “Firearm evidence in police lockers that could hold the answer to unsolved violent crimes is not being routinely tested, allowing criminals to escape justice.”

The news team found that the larger cities in Ohio, like Cleveland, Lorain, Akron, Canton and Painesville, tend to use the NIBIN database more routinely. For example, they reported that police in Ohio had 400 “hits” or ballistic matches last year that linked one crime to another. But the investigation found that many surrounding departments only submit a small percentage of the guns they seize for NIBIN processing.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

There could be a number of very rational and understandable reasons for this, but at the end of the day, we can find no reason that we can label as truly good and acceptable. Especially when one considers that the crime of murder silences its victim. Unable to speak, the victim depends upon the police and the courts for justice.

The cry for justice came through loud and clear in the WKYC-TV piece when Tara Price, who lost a son, said, “Why wouldn’t you be using the system? You have a system that you could use. And it’s a possibility that you might get a hit.” Price further expressed her frustration with this and the fact that the person who killed her son has yet to be identified. She said, “So I’m very upset. I’m very disappointed.”

So how does one respond to Tara Price and the many other mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers of victims when they ask why a tool that has been proven to help police solve crimes, and sustained with taxpayer dollars, is not being used to its fullest potential?

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Among the law enforcement officials the WKYC-TV team interviewed were Parma, Ohio, Police Chief Robert Miller and Ohio Attorney General and former U.S. Senator Mike DeWine. Chief Miller indicated that his department had just instituted a policy to submit crime guns and casings to the NIBIN. He said, “We can’t turn the hands of time back…but certainly moving forward we can do a better job.”

Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine said, “It is a great tool…It is, candidly, an under-utilized tool.” He told the news team that he would make it a priority to make sure that police forces know about the NIBIN and use it for every gun. He said, “I will guarantee you we will solve hundreds and hundreds of more crimes…We will get criminals off the streets, and we will ultimately save lives.”

Looking Forward

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As I think about what the police chief and the attorney general told the folks at WKYC-TV, I see that the successful use of the NIBIN really is a matter of policy—enacting a policy mandating its routine use. Within a month of instituting his new policy, Chief Miller saw positive results. The NIBIN helped link a gun that had been sitting in his evidence room in connection with an “unlawful carrying” incident to a shooting that occurred seven years before in Cleveland.

Looking back one last time at the WKYC-TV news piece, I am reminded that, first and foremost, we should be in a crime fight—not a gun fight. Therefore, we need to make sure that our “crime-fighting houses” are in order to most effectively identify and stop armed criminals.

Check out these 11 Brave Citizens Who Took Down Armed Criminals!

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below