The author found the Merkel action to be as smooth as any he’s ever experienced. Everything about the gun worked flawlessly. He used the six-ounce single set trigger for all test groups.

They say there are few things in life that are certain, but one of them is knowing that any bolt-action rifle coming out of Germany these days is going to be as different from the ’98 Mauser as possible. Which is really ironic, because here in the States our gunmakers have always striven to stay well within the basic design parameters set by the Mauser. Yet in Germany, where the design originated, gunmakers go to extraordinary lengths to come up with unique—even bizarre—bolt-actions. Their motto seems to be: “The further removed from the `98 the better.”

Be that as it may, I always relish the prospect of examining any new German rifle, because there are always unique features to be found and invariably the actions are incredibly smooth and bind free. The Merkel KR1 is no exception. I first saw the gun at the 2007 SHOT Show, where it was being displayed for the first time by Merkel’s importer, Merkel USA (7661 Commerce Lane, Trussville, AL 35173). This newest Merkel is but one of a mind-boggling array of rifles and shotguns produced by this maker, the origins of which can be traced back to 1600. Located in Suhl, a picturesque town nestled among the verdant mountains of the Thuringen Forest, Merkel turns out over/under and side-by shotguns of sidelock and boxlock design, incorporating Jaeger, Kirsten and Greener lock systems. The firm also produces Drillings and single-shot and double rifles in addition to the KR1 bolt-action.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

A cowling of lightweight alloy surrounds the bolt, but it’s a non-stressed component that serves merely to support and guide the bolt.

I had the pleasure of visiting Suhl and the Merkel factory a couple of years ago, and I can tell you it is quite an impressive facility. There is no lack of the latest CNC and EDM machinery, but what you see most throughout the factory is handwork: polishing, fitting, more polishing and more fitting. The town of Suhl was founded and built by gunsmiths, for in addition to Merkel it is the ancestral home of Anschutz, Krieghoff, Heym, Sauer, Steyr and Haenel, to name a few.

First Impressions

Anyway, upon seeing the KR1 for the first time, I was struck by its unique and highly distinctive appearance. For one thing, there’s no loading port, just a butterknife bolt handle sticking out of a cowling of sorts, with nothing like a conventional bolt to be seen. At each side at the front of the cowling, which is a lightweight alloy of bronze color that nicely contrasts the blued steel barrel, are forward-projecting ears that straddle the chamber portion of the barrel. All mechanisms within are completely protected from the elements. It’s really quite an elegant-looking rifle.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Of course, raising the handle and opening the action pretty much answered all the questions that were running through my mind. I immediately was struck by how smooth and quiet the action is. The bolt—or rather the cowling that surrounds the bolt—reciprocates on T-slot rails machined into the upper edge of the lower receiver unit.

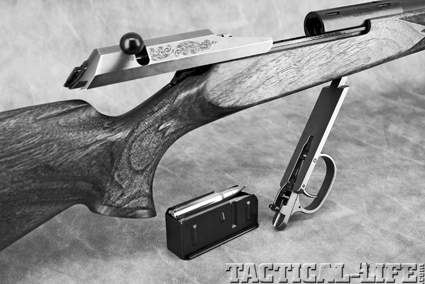

Like the Browning A-Bolt, the “floorplate” on the Merkel is hinged, but the magazine does not attach to it. Note that the trigger moves with the unit.

Having said that, opening the action does, indeed, expose a somewhat conventional-looking bolt head having two rows of three lugs oriented on 120-degree centers. Also conventional is a recessed bolt face, a plunger-type ejector and an extractor that moves radially within a T-slot in one of the locking lugs.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Like so many European-made rifles that have debuted over the past 25 years or so, this one has the bolt locking directly with abutments within the barrel itself, a feature that makes barrel interchangeability more practical. By replacing the barrel, bolt head and magazine box, it is possible to switch from, say, a .30-06 to a .338 Winchester Magnum.

Direct lockup offers several other advantages as well—some practical, some theoretical. First and foremost, by having the bolt lock up within the barrel, the number of stressed components is reduced by a third—i.e., from three to two. In a conventional bolt-action the bolt engages abutments within the receiver ring, thereby transferring firing stresses to it as well as to the bolt and barrel. In the case of the KR1 and similar guns, only the bolt and barrel are involved; the “receiver” needs serve only as a housing for the bolt, trigger unit and magazine. For that reason the receivers of such guns can be of a lightweight alloy. On paper, at least, direct lockup would seem to be superior to the Mauser system, because there are fewer stressed components and therefore less vibration.

Lacking a receiver, the Merkel has a shorter overall length than a conventional bolt gun. The Remington 700 above sports a 22” barrel, the Merkel below it has a 21.5” barrel, yet there’s still about a 2-1/2” difference between them.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Also, with the barrel serving the same function as the receiver ring in a Mauser-type action, you eliminate that portion of the gun normally taken up by the barrel shank/receiver ring. The net result, all other things equal, is that you save in overall length. For example, the test gun I was sent was in .30-06 and therefore sported a standard-length action, yet with a 21-1/2” barrel the overall length of the rifle was slightly more than 40”, or about 2-1/2” shorter than a 22”-barreled Remington 700 in the same caliber.

Just as the bolt needs nothing other than a support structure to keep it in alignment with the chamber as the action is cycled, the barrel needs only a V-block of sorts to keep it aligned with the bolt. That’s why it’s fairly easy to incorporate barrel interchangeability into a direct-lockup system. Only two threaded studs welded to the bottom of the barrel shank are needed to position the barrel and provide idiot-proof barrel-changing capability. In the case of the KR1, two captive Allen-head machine nuts secure the barrel to its V-block. The forward one is exposed at the front of the floorplate tenon, the other is exposed when the integrated floorplate/trigger-guard unit is dropped down. In that respect this rifle is similar to the Browning A-Bolt in that the entire bottom metal unit is hinged at the front. A release latch just ahead of the guard bow drops the floorplate, exposing the detachable box magazine. Unlike the Browning, however, the box does not attach/detach from the floorplate, so it doesn’t drop down with it. The box is simply trapped between the floorplate and the lower receiver unit and drops out when the bottom is opened. This magazine can be charged from the top, just like a conventional bolt-action—a very good feature.

Everything about the KR1 is flush with the stock surface, and there are no protruding components other than the bolt handle.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Trigger Talk

Compared to a Mauser or Winchester Model 70 trigger, the KR1’s is typically complex—and, being a set trigger, doubly so. The finger piece is attached to the bottom metal unit and therefore drops down with it when opened. The actual trigger mechanism is integrated into the lower receiver unit I spoke of, which is mated to the stock and without which the gun can’t function. It’s oh so different from our bolt-action rifles.

The three-position safety is conveniently located on the rear tang where it falls under the thumb. In the center of the thumbpiece is a locking tab that must be depressed to move it fore and aft. Fully rearward locks the bolt and blocks the sear. In the central position the sear is still blocked, but the action can be cycled for safe loading and unloading.

Pushing the trigger’s finger piece forward about a quarter-inch activates the set trigger, which on the test gun broke at a very light six ounces. Once set, it can be deactivated by engaging the safety and pulling the trigger. In so doing, the system reverts to functioning like a conventional trigger—in this case one that broke at 2-1/4 pounds, which is light enough to make the typical trial lawyer lick his chops.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Sighting Options

Like most rifles meant for the European market, our test gun wore iron sights, and they were of typically rugged construction. The rear blade is one piece and machined from solid steel, as is the base on which it sits in a dovetail that allows windage adjustment only. The front sight blade is spring-loaded to absorb inadvertent blows and can be replaced in the field.

A cantilever-type scope mount that attaches to the barrel is furnished with the gun. The locking levers move only 150 degrees from being tightly secured to allowing scope removal. If sold separately, this mount would surely cost at least $300.

Because there is no fixed receiver, the scope mount must necessarily engage the barrel itself in the kind of cantilever arrangement seen on rifled slug guns. Two pairs of dovetail slits provide the attachment points for Merkel’s own quick-detachable scope mount, which is furnished with the gun. Like so many aspects of this rifle, the mount reflects a great deal of engineering and machining know-how. The clamp levers, which have locking tabs, move through an arc that’s only 150 degrees from fully locked to unlocked. It’s really quite ingenious and very fast; you can attach or remove a scope in 20 seconds.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Shots Fired

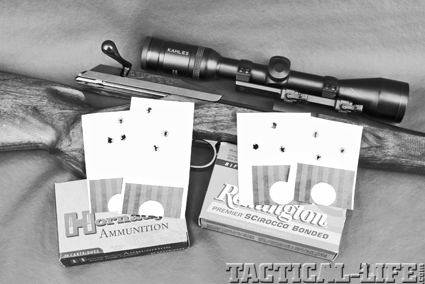

The best group averages were turned in by Hornady’s Light Magnum 165-grain SST and Remington’s Premier 150-grain Scirocco loads. Both averaged three-shot groups of 1-1/4”, which from a 6-pound 14-ounce rifle is more than acceptable accuracy.

For testing, I mounted a Kahles 3-9×42 scope. The rifle alone weighed in at 6 pounds 14 ounces; with the Kahles aboard it went 8 pounds 6 ounces. With the most popular bullet weights being 150 to 180 grains, that’s what I stuck with for testing. The brands/loads used were Winchester Supreme 150-grain Ballistic Silvertips, Hornady 165-grain Light Magnum SSTs, PMC Golds with 165-grain Barnes X-Bullets, Federal Premium 165-grain Nosler Ballistic Tips, and Remington Premier 180-grain Scirocco Bondeds.

As expected, the test gun was a joy to shoot. Everything functioned smoothly and effortlessly. The magazine charges easily by simply pushing the rounds straight down against the follower; you don’t have to slide each cartridge rearward under the feed lips. For a set trigger in the non-set mode, this one had very little creep before it broke crisply. Moreover, the firing-pin fall is less than 1/4”, so the lock time is very quick indeed—probably around two milliseconds, I’m guessing.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As for the set trigger, one can argue its efficacy in a hunting rifle, but I found myself using it for every shot when shooting for groups. Unless you’ve tried a six-ounce trigger, you can’t appreciate what a joy it is to use—but man oh man do you have to be careful with it.

Making It for America

At the time I reviewed the KR1 it was only available with what I call a “Bavarian-style” stock, which is characterized by a humpback comb, a cheekpiece that looks like it belongs on a coo-coo clock, and a sliver-like forend. Also at that time the starting price was a hefty $2,995. That’s because the “standard” model had a gold-anodized receiver, engraving, fancy wood—all the stuff that’s close to the hearts of German hunters. Merkel has since come out with a “Yank” version: a plain Jane iteration with an American-style Classic stock that carries an MSRP of $1,995. Surprise, surprise: Suddenly the company is finding that it’s selling a lot more KR1s in the States. And well it should, for I guarantee that if you examine one, you’ll agree that it’s one helluva lot of rifle for the money—a rifle that’s innovative in its design, appearance and functioning and one that is superbly crafted.

For more information, visit merkel-die-jagd.de/en.