The Right Gun and Method of Carry Are Essential to First-Time Buyers and Seasoned Pros Alike

If there’s one thing that’s true in the firearm world, it’s that there’s a lot to know about how to choose a handgun.

There are two schools of thought at work here; one is “old school” and which means revolvers, the other is the current trend toward new subcompact and ultra-compact semiautomatics in calibers from .380 up to .45 ACP. In my experience, the choice between a revolver and a semi-auto has always been very personal. If you grew up around a father, older brother, or another family member who favored one style of gun over another, that has probably biased your preferences, but for first-time consumers and new CCW (concealed carry weapon) permit holders with no preconceived notions, the choices are wide open. Both revolvers and semi-autos present options that need to be given genuine consideration.

Personal Defense World’s Guide on How to Choose a Handgun

How to Choose a Handgun: Compare Revolvers vs. Semi-autos

This is a debate that has, believe it or not, been ongoing for more than 100 years! Does it make the topic of how to choose a handgun a bit difficult? Sort of, but it’s pretty entertaining to watch die-hard enthusiasts from both camps argue their stances.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The greatest difference today is the advent of new technologies both for revolvers and semi-autos that have marginalized many of the distinctions between them, such as caliber choices and ease of use combined with new engineering and materials that allow larger caliber pistols to scale down in size and weight to dimensions once limited only to small caliber semiautomatics. These smaller-sized guns have brought many more options to the table and given semi-autos a decided edge in popularity, particularly among women who make up a sizable percentage of new CCW permit holders.

Historically, throughout much of the early to mid-20th century, women tended to favor small caliber semi-autos, mostly .25 ACP and .32 ACP pistols for concealed carry or self-protection, while men leaned toward .38 caliber revolvers like the Colt Detective Special and Colt Agent (both long gone), or any number of Smith & Wesson J-frame models which are still in production and have retained a solid following into the 21st century. Obviously, if the inherent advantages of a revolver were not evergreen we wouldn’t have modern variants chambered for the same calibers as semi-autos like .380 ACP, 9mm, and .40 S&W, nor new models with composite frames or construction using ultra-light alloys like S&W’s Scandium series guns.

Revolvers

The fundamental advantages of a small-frame double-action revolver begin with ease of use. A revolver has no manual safety; you draw, aim, and if the situation demands, pull the trigger. Alternately with most revolvers, one can cock the hammer manually; firing single action generally increases accuracy as well as greatly reducing trigger pull effort. And there is no question as to whether a round is chambered in a revolver, if the gun is loaded there is a chambered round. Even if you take the ultimate safety precaution (aside from a trigger lock) and do as gunmen often did in the Old West and keep the hammer resting on an empty chamber, when the trigger is pulled on a double action revolver (or the hammer manually cocked) the cylinder rotates to the next chamber, which is loaded.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The question of a chambered round is also addressed by many semi-autos which have loaded chamber indicators, but only those with very obvious and easily seen or felt indicators are of value in a high-tension situation where there is precious little time to go looking for a more subtle difference. Guns with obvious loaded chamber flags, like the 9mm Ruger LC9, are an excellent choice, especially for first-time handgun owners.

Semi-Automatics

Semi-autos were originally designed with a manually operated safety mechanism to prevent accidental discharge, thus the process (of the wise) was to carry a gun with a chambered round and safety engaged (the proverbial “cocked and locked” method), draw, release the safety, aim and pull the trigger, thus adding one additional step to the process. Conversely one could carry the gun without a chambered round and after drawing manually cycle the slide and load the first cartridge. A vast majority of semi-autos still use the traditional manual safety design, but not all.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Glock was one of the first armsmakers to eliminate that distinction in the early 1980s with the Glock 17. More than a quarter century later Glock has an entire line of various caliber and frame sizes all utilizing the Safe Action Trigger design, which essentially puts the semi-auto into the same “ease of use” category as a revolver. The trigger pull is the sole discretionary safety, although Glocks and other semi-autos employ similar designs and nearly all revolvers incorporate internal (passive) safety mechanisms to prevent accidental discharge if the gun is inadvertently dropped. With a Glock-style system, a secondary safety mechanism incorporated into the face of the trigger requires a direct and positive linear pull along with the trigger to disengage internal safeties and allow the firearm to discharge. With the Glock system, it is draw and fire, so scratch the manual safety and one very big distinction between revolvers and many modern-day semi-autos.

Cartridge Capacities

Cartridge capacity and ease of reloading are the next most important considerations. Revolvers, with very few exceptions, limit capacity to six rounds, five in most small frame snub nose (2-inch barrel) models chambered in .38 Special (.38 +P or .357 magnum) caliber. This limit also applies to revolvers chambered in semi-auto calibers like .380 ACP, 9mm, .40 S&W, and .45 ACP. Any question of accuracy between a revolver and semi-auto has little merit as both in comparable calibers and approximate barrel lengths are generally identical, it is reloading where the semi-auto quickly excels.

Even the most proficient with a revolver have to follow the same steps when reloading; depress the thumb release with the right thumb, push the cylinder outward with the first three fingers of the off-hand, thrust the ejector rod back to expel spent shell cases, and then reload the empty chambers, either singularly or using a speed strip or speed loader. With a semi-auto the reload requires activating the magazine release to drop the empty magazine, inserting a loaded magazine, and releasing the slide to chamber the first round. With practice, this can be done in seconds and without taking the gun off target!

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

While these differences in handling may seem to be stating the obvious, the virtues of a revolver cannot be overlooked. There is a simplicity and ease in its function that has not been surpassed since Samuel Colt patented the single-action revolver in the mid-1830s. A modern double-action revolver (most of which can also be fired single-action) is the easiest handgun to operate and with far less potential for either a mechanical failure or jam. Thus the choice is today, as it was more than a century ago, one of weighing the pros and cons and finding your own level of comfort and proficiency with a handgun.

How to Choose a Handgun: Understand Calibers & Consequences

There is one basic rule here, Newton’s Law that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction, in other words, the bigger the caliber the greater the recoil. This is where training time is essential. If there is a shooting range nearby that has certified instructors and rents guns for training and target practice, avail yourself of this opportunity to try both revolvers and semi-autos and in calibers ranging from .380 Auto up to .45 ACP in semi-autos and .38 Special to .357 Magnum (or .44 magnum) in revolvers.

The quick lesson learned from this exercise is to find out what an individual can handle in terms of firepower. Often we discover that many people are not as “recoil sensitive” as they thought, while others find harsh recoil so uncomfortable they prefer not to shoot that type of gun. This is trial and error and a function of practice necessary before making the decision on which gun and caliber to purchase. Nowhere can this be better accomplished than at a local shooting range or a shooting club.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Carry Small, Carry Wise

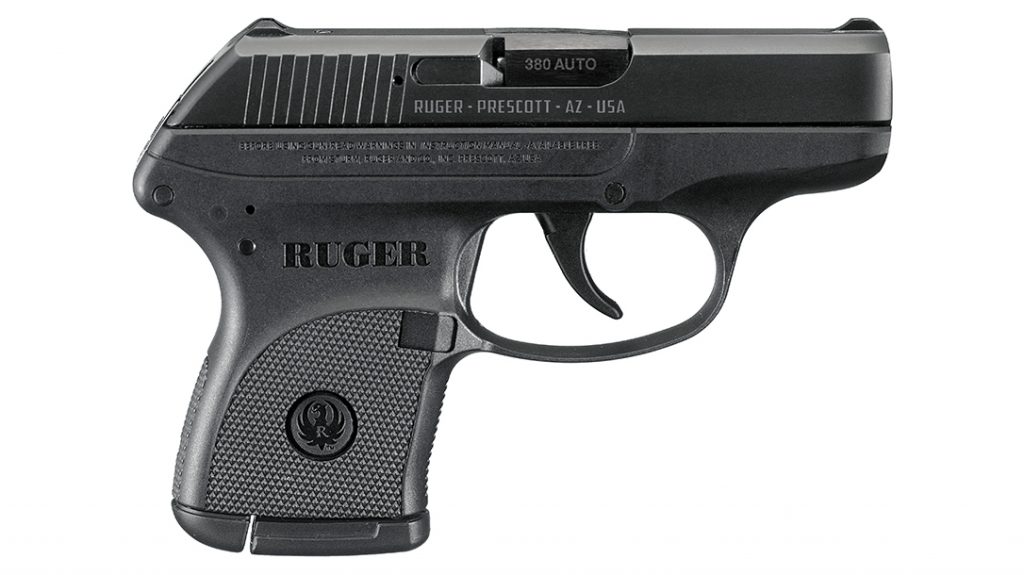

The most popular concealed carry guns on the market are .380 Autos. These are all small, easy-to-carry sidearms like the Ruger LCP. Capacity is six in the magazine plus one chambered. Seven rounds of .380 in a defensive cartridge like Hornady Critical Defense 90 gr. FTX; Federal Premium Personal Defense Low Recoil 90 gr. Hydra-Shok JPH (jacketed hollow point); or Speer Gold Dot 90 gr. hollow point, offer greater velocities, bullet penetration, and expansion than older, traditional FMJ (full metal jacket) .380 rounds.

These vast improvements in ballistic performance have given the .380 a new life as a 21st-century defensive cartridge. The ease with which a .380 can be carried allows options from traditional belt and paddle holsters to inside-the-waistband (IWB) rigs and for the vast majority of users, pocket holsters that provide excellent concealment, ease of carry, and reasonably quick access.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

While everyone must find the means of carry that is best suited, a .380 auto or a .38 caliber snub nose revolver are the easiest to manage on a daily basis. I have personally carried either a .38 snub nose revolver (an S&W Performance Center Model 640) or Ruger LCP .380 for many years, the S&W for almost 20. Both have proven easy to handle, accurate and reliable. There are many other .38 Special revolvers and .380 autos available that offer the same function and ease of carry, making this an excellent stepping-off point for selecting a first gun in a small caliber or as a secondary (backup) gun for personal protection.

Carry Big – Capacity and Caliber

While many with a CCW permit are satisfied with a small caliber revolver or semi-auto as their only carry gun, others ascribe to a firearms interpretation of an old automotive saying, “There is no substitute for cubic inches.” In the world of handguns, the minimum standard here is 9mm, a global staple for military, law enforcement, and personal protection for over 100 years.

The 9mm, like the .380, has been enhanced with commensurate increases in velocity, penetration, and expansion capabilities. This is more than a logical progression because a .380 is a 9mm short. Improve one, improve both. A .38 Special +P is also in the same ballistic range and all of the aforementioned improvements are similarly available for revolver ammunition, though only applicable and safe to use in handguns clearly rated for .38 Special +P or .357 Magnum ammunition.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The 9mm was traditionally a large handgun suitable for multiple uses but less easily concealed due to frame size, barrel and slide length, and weight. That all began to change in recent years with new technology that has made it possible to build a 9mm that is barely larger than the shadow cast by a .380 pocket pistol. The trade-off has been somewhat harsher recoil due to reduced weight, frame, and barrel dimensions, and a reduction in standard capacity.

Among leaders in this field of subcompact, 9mm semiautomatic pistols are Ruger (LC9), Kahr (CM9), Beretta (Nano), Sig Sauer (P938), and Kimber (Solo) all with a 6+1 capacity except for the Ruger which has 7+1. All five are excellent choices for a 9mm concealed carry sidearm and all of the various holsters available for .380s are also available for these scaled-down 9mm pistols. The Nano will also soon be available chambered in the more powerful .40 S&W caliber and Glock offers two subcompacts in either 9mm or .40 S&W.

Stepping up to the venerable .45 ACP the most historic of all semi-auto calibers for size and blunt force stopping power, the .45 ACP has been a staple of the American military since 1911, and up until 1985 was this country’s standard military issue handgun. The 9mm has assumed that role for the U.S. in general but special ops units still defer to the .45 ACP. For civilian use, the best options for concealed carry have been the Commander and Officer sized 1911 models, which have shorter frames and barrels.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

There are dozens of .45 Autos in this category from the custom-built Wilson Combat line to excellent production models from Colt, S&W, Kimber, and Springfield Armory, among many others. But it is Springfield that raised the bar in 2012 with the introduction of the XDS, the first micro-compact .45 ACP truly in the pocket pistol category. This singular semi-auto places 5+1 capacity into a package that will discretely disappear into a trouser pocket.

How to Choose a Handgun: Know Your Glock Options

For an article that aims (pun intended) to guide new shooters on how to choose a handgun, we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention Glock pistols. Slightly larger in size but designed for concealed carry in a belt or IWB rig are Glock’s compact and subcompact models chambered in 9mm, .40 S&W, and .45 ACP, among other popular calibers. All are smaller in dimensions than a Commander or Officer-sized Model 1911 and offer higher standard capacity (6+1 for most 1911-based designs; 15+1 for 9mm Glock 19, 10+1 for subcompact Glock 26; 9+1 for Glock 27 in .40 S&W; 10+1 in .45 ACP with Glock 30/30SF).

Also consider that there are 9mm, .40 S&W, and .45 ACP snub nose revolvers on the market for those who prefer a 5- or 6-shot backup chambered in the same caliber as a primary semi-auto carry gun.

The bottom line is that today there are more options out there in a concealed carry or personal defense sidearm than at any time in history. The basic choices between revolver and semi-auto remain and making the right choice is essential. The main focus of how to choose a handgun requires a shooter to select the size, shape, and caliber handgun that is most appropriately suited for their height and weight and their ability to handle. The best advice we can give on how to choose a handgun is to consider all the factors and when possible test the style and caliber you want before buying. Without getting melodramatic, this really could be a life-and-death decision.