The very first snub nose revolver was a Colt. And you can erase the image of a Detective Special or even a 2-inch barreled Peacemaker from your mind. The first Colt snub nose was a Paterson. It was also the very first Colt revolver, built all the way back in 1837! A small pocket pistol chambered in .28 caliber, Sam Colt called it the No. 1, or Pocket Model revolver. It has since become more popularly known as the Baby Paterson.

A Short History of Snub Nose Revolver Evolution

Pictured above is Sam Colt’s personal No. 1 model. This demure, five-shot revolver was the beginning of an era, the first production percussion revolver with a cylinder mechanically advanced to the next chamber by cocking the hammer. Colt also offered the No. 1 in a slightly larger .31-caliber model with both versions available with a 2-1/2-inch barrel. Colt surmised that at close range, five shots were four better than the popular Henry Deringer! Production began in 1837 and concluded roughly a year later.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Unfortunately, Colt’s Paterson revolvers were not the success he had hoped they would be, or for that matter, his entire first business venture in Paterson, New Jersey, which failed in 1842. But Sam Colt would be back in 1847 with the massive .44-caliber Walker Dragoon and a succession of .44 caliber Dragoon models throughout the 1850s and early 1860s. But what about those small guns with big holes? Colt was on the way there by 1848 with the Baby Dragoon model, a scaled down version of the First Model Dragoon but without loading lever.

Gaining Momentum

In 1849 he added a new model in .31 caliber fitted with a loading lever, a feature which made the pocket pistol imminently popular for more than 20 years, with production of the percussion models ending in 1873. With the beginning of cartridge conversion models in .38 caliber (pictured below), it would remain in production into the early 1880s.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

This is, however, getting ahead of the story, because Colt’s percussion pocket pistols were to play a significant role during the Civil War and for years after with variations created both at the factory and by individual gunsmiths. The latter, likely inspired by Colt’s own initiative to produce a limited number (perhaps 50) snub nose .36-caliber 1862 Pocket Police models (pictured below), essentially the origin of 20th century .38-caliber Colt snub nose revolvers.

If Colt could shorten the barrel on the Pocket Police, one then could certainly do the same to a Pocket Model of Navy Caliber, or even a full-size 1851 Navy, as some did quite beautifully during the Civil War (pictured below).

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

“Somebody get me a saw!”

If you could shorten the .36-caliber Navy models, then why not a full-size .44-caliber revolver? Obviously, the 1860 Army was next, and as it turned out, it was an ideal choice, the first small gun with a big hole, but not the last! Pictured below is an original Civil War-era 1860 with cut down barrel and modified backstrap for smaller, rounded grips.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

When many of these same guns were converted to metallic cartridges in the early 1870s, the large-caliber snub nose revolver was fully born. Shown below is an 1860 Army Conversion to .44 Colt, with the frame modified to a bird’s head-style grip.

From the mid-1860s to the latter 1870s, there was a rapid evolution of snub nose revolver designs and calibers. Shown below, an 1848 Baby Dragoon, 1862 Pocket Police, 1860 Army percussion and cartridge conversions, and a radically cut down 1873 Peacemaker.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

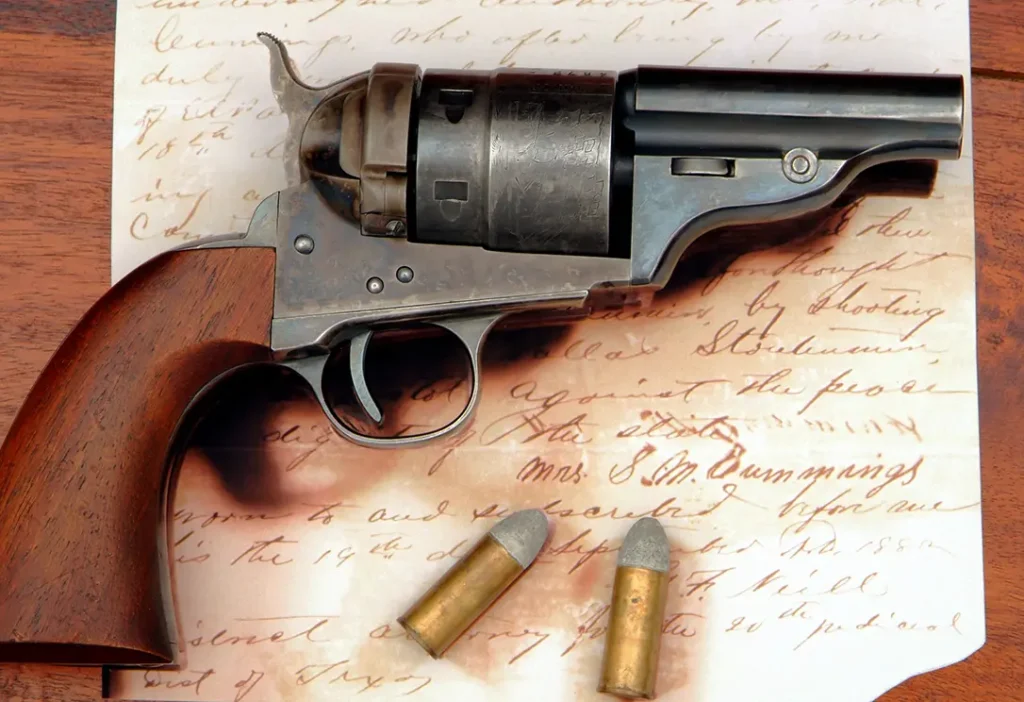

1860 Army Richards-Mason Conversion

Among the most memorable was an 1860 Army Richards-Mason conversion cut down to 2-1/2 inches for El Paso, Texas, lawman Dallas Stoudenmire, a .44 he carried butt forward in his left trouser pocket. Below is a faithful reproduction of Stoudenmier’s Colt, a gun that inspired countless other snub nose variations, and they were plentiful. By the 1870s there was no shortage of talented and willing gunsmiths to do the work out West.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The snub nose revolver with 3-1/2 inch barrel had become a production model offered by Colt’s on the Single Action Army frame in 1888. They came to be known as the Sheriff’s or Storekeeper’s Model (below). Both monikers suited their intended uses, by lawmen and outlaws alike, as an easily concealed backup gun, and for store owners, as a quickly retrieved pistol kept close to the cash drawer.

Establishing the Snub Nose

An idea postulated by Samuel Colt in the 1830s had become a standard of design by the turn of the century with Colt’s, Smith & Wesson, and the vast majority of U.S. and European arms makers offering various styles of medium- and larger-caliber revolvers with 2- to 3-1/2-inch barrels, many with altered frames to accommodate their intended use.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Bird’s head grips were a common alteration, and at least one Peacemaker with a 2-inch barrel was fitted with bird’s head style grips and a cutaway triggerguard. This idea was not lost on one of Colt’s most famous 20th century sales representatives, arms instructors and gunsmiths, J. Henry FitzGerald.

The Fitz Specials

It should be considered that the American West did not simply dry up and blow away like a tumbleweed when the calendar page turned to January 1900. It is well accepted that the period lasted into the 1920s, which brings us to FitzGerald and his influence on snub nose revolvers. Around 1918, FitzGerald accepted a position with Colt’s.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Historian and author Kevin Williams wrote: “His formal role evolved into that of ballistics expert. Informally, he used his fast-draw and trick-shooting skills, his gunsmithing ability and his 10-gallon hat, fancy gun rigs, and garrulous personality to become Colt’s best promoter and front man.”

Fitz Colts for Lawmen

From the late 1920s through 1940, he also built his own versions of Colt double-action revolvers, mostly for lawmen, including renowned Texas Ranger “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas, who carried one of FitzGerald’s cut down Colt double actions as his backup. The custom-built Colt’s came to be known as “Fitz Specials” and ranged from the New Service .45 Long Colt to the .38-caliber Colt Police Positive, Banker’s and later Detective Specials. Nearly all of the guns had several features unique to FitzGerald’s design; most had cut down and smooth-surfaced hammers to reduce the chance of the gun snagging on clothing, the front third of the triggerguard was cut away and the edges rounded to allow more rapid contact with the trigger, the ejector rods were shortened and the heads removed, and barrels cut down to the minimum length for the caliber, generally no more than 2 to 2-1/2 inches.

About 50 New “Service” models (like the example shown above) were built in the FitzGerald style, along with Bankers, Detective Specials and Police Positive models. They essentially became double-action-only revolvers with reworked actions to lighten trigger pull. His earliest and personal favorite was the Colt New Service in .45 Colt. Wrote FitzGerald, “I choose the .45 New Service because it is the most powerful handgun, and with a two-inch barrel and cutaway in the same manner as the light model it is king of them all.” It was truly a small gun with a big hole!

Contemporary Influences

The notoriety achieved by the Fitz Specials, and snub nose revolvers in general, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries has carried on into the 21st century; the snub nose revolver, despite the popularity of small semi-autos today, is still a staple of personal defense and concealed carry with large-caliber models continuing to be a proven design. Back in the early 1980s, specialty retailer Lew Horton had a limited run of special S&W Model 25-2 revolvers built (left in the photo above) which utilized the N-Frame .45 ACP revolver combined with an L-Frame backstrap, combat-style grips and a 2-1/2 inch barrel. Fast forward to the 21st century and S&W offered the same design as a Scandium (light alloy) model with a titanium cylinder, 2-1/2 inch barrel and combat-style grips. Two guns entirely inspired by the snub nose revolvers of the American West.