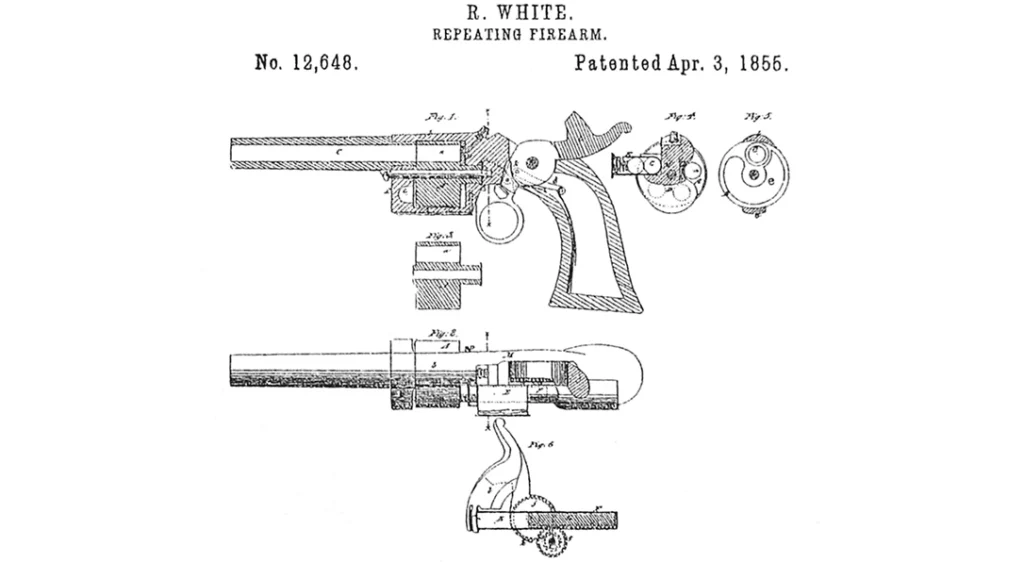

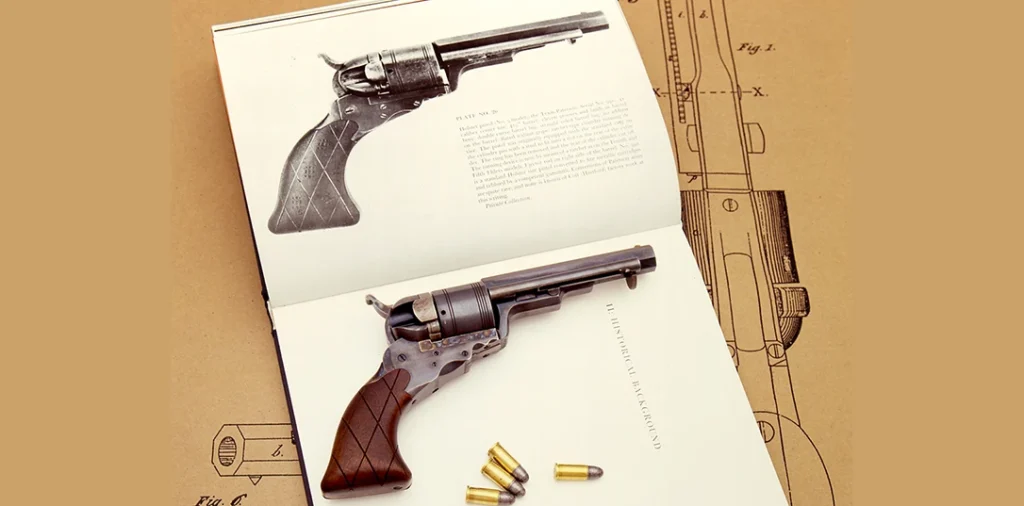

War is often the mother of invention, or at least the swift kick that inspires change. By the late 1860s, American arms manufacturers were being tasked to find ways to repurpose their Civil War-era percussion models to accommodate the variety of metallic cartridges that had come into use during the war. Smith & Wesson, however, made no such attempts in the 1860s having purchased the patent rights for the bored though, breech-loading cylinder in 1855 from inventor Rollin White. The White patent gave S&W sole domain in America over cartridge loading revolvers throughout the entire Civil War (a thorn in the side of the Ordnance Department which would come back to haunt S&W when they sought a patent extension from the U.S. government, which was subsequently refused).

However, until the S&W Rollin White patent expired in 1869, no U.S. armsmaker could build a cartridge loading revolver, leaving Colt’s, Remington and others hamstrung throughout the conflict and the door open for foreign manufactures to export cartridge loading revolvers to both the North and South throughout the Civil War. Not surprisingly, by 1869 everyone was scrambling to find ways to convert cap and ball wheelguns into cartridge loading versions, with Colt’s and Remington leading the way.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

First Cartridge Conversions

E. Remington & Sons was the first in 1868, converting their .44 caliber Army and .36 caliber Navy percussion models into cartridge guns (a proprietary .46 caliber rimfire cartridge for the 5-shot Army conversions and .38 caliber rimfire for the 6-shot Navy). Remington circumvented the Smith & Wesson patent through an agreement to pay a $1 royalty on every gun sold. Unfortunately for the New York armsmaker, their early conversions were not that popular, leaving an opening that Colt’s capitalized upon between 1871 and 1872 by introducing an entire line of Richards and Richards-Mason patented conversions ranging from small .38 caliber pocket models to the very popular 1851 Navy and 1860 Army cartridge models in .38 and .44 caliber, respectively. But that isn’t where Colt’s started. They began before the White patent expired, by experimenting with .44 caliber Dragoon models!

Unlikely Cartridge Revolver

Prior to 1869, the Hartford armsmaker built a number of experimental cartridge conversions including a 3rd Model Dragoon chambered for the .44 caliber Henry rimfire cartridge, and another in the Thuer style for .44 centerfire. Both were viable designs, but neither was put into production. Nevertheless, between 1868 and into the early 1870s, numerous conversions were done on 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Model Colt Dragoons, among the largest caliber American percussion arms of their time. Although outdated by the end of the Civil War, the use of 1850’s era Dragoons by Union and Confederate forces kept these hefty .44 caliber revolvers popular until the advent of Colt’s Richards and Richards-Mason cartridge conversions. Interestingly, even with the introduction of the Colt Peacemaker in 1873, .44 caliber S&W topbreak cartridge revolvers in 1870, and Remington’s Model 1875, countless civilians were still carrying converted Colts and other percussion-era revolvers well into the late 1870s and early 1880s. They either already had them, or found the ready availability and comparatively lower cost of conversions more appealing.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Among the handful of Dragoon conversions known, only a few can be traced directly to Colt’s; a 3rd Model (in the 12300 or 12400 serial number range) converted to fire .44 Thuer centerfire and decorated in the large donut scroll style of engraving by Gustave Young, and a factory experimental conversion, No. 15703, chambered for .44 caliber rimfire. This example used a specially manufactured cylinder of two-sections silver soldered together, combined with a wide, channeled breechring. The right recoil shield was also dished out to permit the loading and unloading of the cylinder without removing it from the gun, although they were not fitted with any type of ejector housing. Of the two Colt’s prototypes, the two-section silver-soldered cylinder became a common link among most Dragoon conversions, likely all of which were done by gunsmiths. Among those known examples there were two common variations, one with the hammer milled flat to strike an internal floating firing pin held in the breechring and those with firing pins riveted to the hammer like the example shown; which is a reproduction of the Colt Gustave Young engraved experimental model built around 1868. As with the original, the contemporary example, built on a Colt 2nd Generation 3rd Model Dragoon, uses a percussion cylinder with the back cut off and replaced by a bored through cylinder plate silver soldered into place.

Most Dragoon conversions were chambered in .44 centerfire, two of which changed hands in the December 2008 Rock Island Auction. Several others have been pictured in books by R. L. Wilson; R. Bruce McDowell (pages 381, 389, 390, 391 of A Study of Colt Conversions and Other Percussion Revolvers) and in the author’s 2006 book Metallic Cartridge Conversions (page 76). Needless to say, Dragoon conversions are a rare gun.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The reproduction of the Colt conversion c.1868 pictured above was handcrafted by Colorado gunmaker R.L. Millington and engraved by John J. Adams Sr. in the Gustave Young large donut scroll style used on the Thuer experimental model, combined with the cylinder modifications from the .44 rimfire conversion. The 3rd Model Dragoon conversion copy was chambered in .45 S&W.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

While a Colt Dragoon conversion is a rare bird, consider how rare a Walker Colt conversion would be. The question is, “Were there any?” And the answer is “yes”, at least once! The example pictured in the archival photo above, from the Connecticut State Library, shows a Walker originally issued to Texas Ranger Company A, with serial number 137. The design, which is superbly documented, shows a revolver that has received a Richards-Mason style conversion using the original cylinder with the back cut off, cylinder ratchet milled, chambers bored through, and an added breechring. The original hammer has been fitted with a firing pin and the right recoil shield deeply relieved to match the breechring loading gate cutout. The size of the loading channel is such that it also exposes the cylinder ratchet, which was common on most conversions. The gun uses an early-style, and somewhat crude, spring loaded ejector housing with a Colt-style round (donut shaped) ejector rod head generally seen on early Model 1873 Colt Single Action revolvers (through approximately 1884). It also has a loading gate with an internal spring actuated plunger, another feature based on Richards, Richards-Mason, and 1873 Colt design patents. This would give the impression that the conversion on this Texas Ranger Walker was done in the early 1870s, which makes this gun, and the singular .45 Colt caliber reproduction of that gun pictured below, (which was done by R.L. Millington for Guns of the Old West), all the more intriguing, and yet there are even stranger conversions to be considered!

By the 1870s a lot of talented gunsmiths knew the rudimentary steps necessary to adapt a percussion revolver to handle self-contained metallic cartridges. Sometime around 1874 a gunsmith in Oklahoma Territory looked up from his workbench into the eyes of a customer and asked him flat out, “Why do want to do this?” Whatever the reason, it seemed reasonable enough for the gunsmith to look at his catalog of Colt’s pistols from 1872 and find a description and illustration of the Richards-Mason 1851 Navy conversion. Only the gun he had been handed wasn’t an old 1851 Navy, it was an 1841 Paterson No. 5 Holster Model!

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The conversion process required cutting off the back of the cylinder and boring the chambers completely through (or making a new cylinder as Colt’s eventually began doing for the ’51 Navy and other percussion models being converted at the factory). The difference in the length of the cylinder was taken up by a manufactured breech ring screwed to the recoil shield. The top of the ring was cut away providing either a tapering hole through which a hammer-mounted conical firing pin could pass for centerfire cartridges or an off center notch on the left for rimfire rounds. Some breech rings had loading gates, others just an opening to correspond with a loading channel cut into the recoil shield.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The design on the Paterson used a Wm. Mason-style breechring and internal spring loading gate combined with a variation of the Mason ejector housing attached to the barrel lug with a screw passing through from the left side. It was a lot of work on an 1851 Navy, adapting the design to the Paterson would have been quite a job. No. 5 Holster model serial number 591 was re-chambered to fire .41 caliber centerfire cartridges and fitted with a barrel cut down to 4.5 inches. There may well have been other Patersons converted to metallic cartridges in the 1870s, if so they are lost to time and this is the only documented example extant.

The original gun is part of the Woolaroc Museum collection in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.The exact physical duplicate pictured is built on a 3rd. Generation Colt Blackpowder Arms Co. Paterson frame and is one of only three copies handmade in the late 1990s by R.L. Millington. All three copies are in private collections today.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Is there any practicality to a Paterson cartridge conversion? It might have seemed a fool’s errand to modify a 30 year old 5-shot Paterson .36 caliber percussion pistol to fire .41 caliber metallic cartridges, but 150 years later this singular Paterson remains unique in the world. Was it the revolver of an eccentric gunman or an old pistol that had some sentimental value? We’ll never know. What we do know about this Paterson is that if one wanted a lightweight pistol that could be easily carried in a waistband, a pistol without a triggerguard, or even an exposed trigger until the hammer was cocked, and in a potent .41 caliber chambering, this would probably have been it.

Here Comes The Starr

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Federal Government had purchased 47,952 Starr double and single action revolvers from the New York manufacturer during the Civil War. As it would turn out, one of the very best conversions from percussion to metallic cartridge was the Starr topbreak single action revolver. The advantage of the Starr as both a percussion arm and later as a cartridge conversion was the topbreak design. By simply unscrewing and removing the large knurled cross bolt that passed through the breech, the barrel and topstrap separated from the frame and tilted down allowing an empty cylinder to be easily replaced with a loaded one.

As a conversion, the Starr was a natural, although the conversions had to have been done by individual gunsmiths as Starr went out of business in 1867. There were two ways in which the guns were modified, which appears to have been a constant, either as a 5-shot, .45 caliber Benet primed centerfire cartridge revolver (mostly double action models) or a 6-shot, .44 Colt conversion on the single action, as pictured, which comprised the majority of known examples.

The Starr’s unique design did away with the conventional cylinder arbor. The Starr used a long ratchet shaft seated into the breech at the rear, which locked into the front of the frame with a conical bolt extending from the cylinder. Because of this design Starr revolvers were less apt to foul since they did not have to rotate around an arbor, and as a conversion, the cylinders offered the same advantage. In making a conversion, a new bored through cylinder had to be fabricated with only six bolt stops (the percussion cylinders had 12 stops, one for each chamber and a safety stop in between). A new cylinder ratchet was either machined or taken from the percussion cylinder and attached. The percussion cylinder ratchet passed through a bored out breechring, which contained a floating firing pin like a Richards Type 1 Colt conversion. A relief cut was then made in the front of the hammer to strike the firing pin. The hammer sight notch remained untouched. They were very simple conversions with no cutout for loading. You simply broke open the gun and removed the cylinder to load it. As a cartridge gun the Starr is exemplary with all the durability of a solid frame revolver and nearly the loading ease of an S&W topbreak.

Pictured above are an antiqued reproduction .44 double action cap-and-ball model and an antiqued reproduction Single Action conversion chambered in .44 Colt. Both guns were handcrafted by R.L. Millington for Guns of the Old West using reproduction Pietta Starr models, which are highly authentic to begin with. The Starr, Paterson, Walker and Dragoon reproductions comprise a set of one-of-a-kind cartridge conversions that may defy logic, but illustrate a period in the Post-Civil War era when folks learned to “make do” with whatever they had.