Over the last few years, Royal Tiger Imports has been selling off a fascinating weapons cache purchased from the Ethiopian government that appears to contain examples of just about every type of firearm ever used there from black powder muzzleloaders of the mid-1800s to Cold War machine guns. How they located and obtained these historic weapons for the American collector market is an adventure story for another time. This story is about their Vetterli-Vitali Model 1870/87 repeating rifles which, on sale, are offered for as little as $149 delivered to your door. Since the youngest of these guns was made about 130 years ago, they are all classified as antiques and don’t need to be transferred through an FFL dealer.

Vatterli-Vitali Model 1870/87

Despite their wildly Steam Punk appearance, Vetterli rifles of any kind, and there were many models in Swiss and Italian service, have never attracted much collector interest here. I believe that’s because what little combat action they did see hasn’t been of much interest to Americans. Not surprisingly, the Italian Vetterli is the most blooded of the class, and most of its battles in Africa were actually fought in the mid-1890s when it was already obsolescent.

The Model 1870/87 was the primary arm of the Italian forces in the First Italio-Ethiopian War (formerly called the Italio-Abyssinian War) from 1895 to 1896. Ironically, some of these rifles were also used by the Ethiopians who, under the leadership of their Emperor Melenik II, decisively defeated the Italian forces at the Battle of Adwa. There’s a reasonable chance that these recently imported Model 1870/87 rifles saw service in Africa in this war and this great battle.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Blooded in Battle

There are other examples of African troops defeating European colonial forces (ex. Battle of Isandlwana), but those victories were only temporary setbacks in the European colonization of Africa. By contrast, the Battle of Adwa was a strategic victory that drove all the Italians from Ethiopian soil for the next 40 years, led to the Italian government officially recognizing Ethiopia as a unified sovereign nation, and toppled the Italian Prime Minister! Among African nations in the colonial period, Ethiopia alone successfully maintained its independence. How they succeeded where others failed has a great deal to do with the characteristics of the geography and the people, their exceptional emperor, and TONS of guns.

At the Battle of Adwa, the Italian General Oreste Baratieri commanded a force of four brigades, one of them made up of native Askari from Eritrea but commanded by Italian officers. Historical estimates of his forces ready for combat on the morning of March 1, 1895 vary from 15,000 to17,500 officers and men. The previous night, against his better judgement to withdraw and resupply, Baratieri reluctantly agreed to a surprise attack on the encamped army of Emperor Melenik II east the village of Adwa. Ethiopian fighting strength was estimated between 75,000 and 100,000 warriors.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

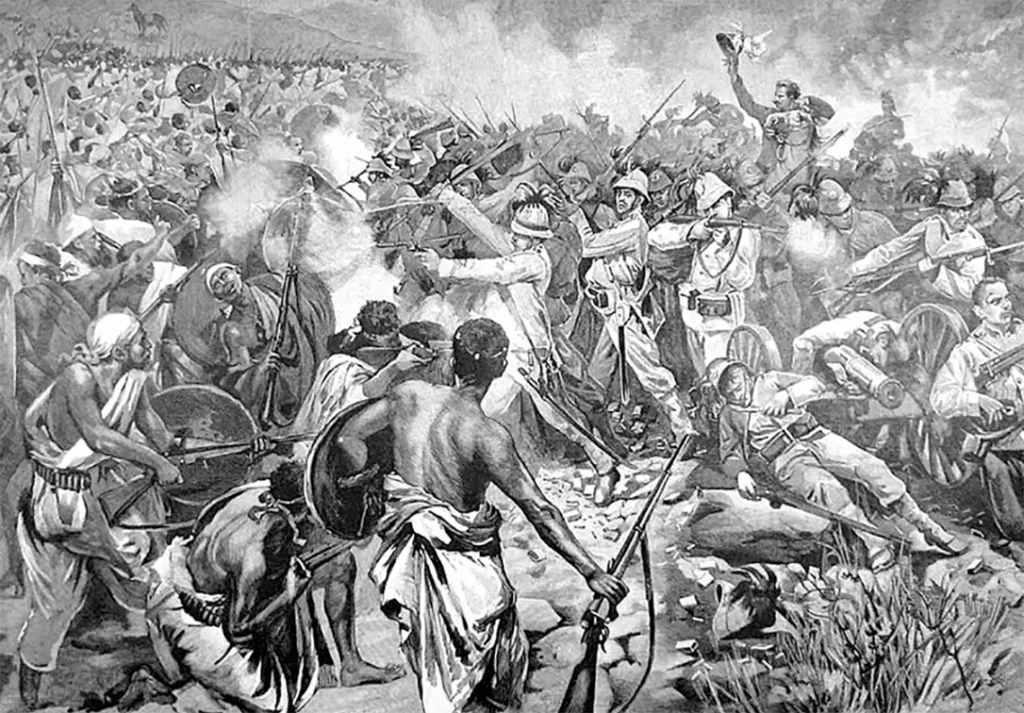

Battle of Adwa

The Italian plan was to march three columns through the narrow mountain passes east of Adwa, take commanding positions on high ground, and draw Melenik II’s army into the confines of the mountain passes where their numerical advantage would be minimized by a narrow front and lack of maneuver room. Thus constrained, the Ethiopians would be cut down by cross fires from the Italian columns. Lacking the leadership, discipline and training of a modern European army, the Ethiopian’s were expected to break and run. That didn’t happen. By late afternoon, Ethiopian warriors had either destroyed or routed the entire Italian force.

The Italian field commanders made a series of grievous blunders throughout the battle which the alert Ethiopians repeatedly exploited, outflanking, enveloping and destroying the Italian’s unsupported, isolated positions, first with rifle and artillery fire, and finally in close combat with sword and lance. Even more so than the United States, Ethiopia at this time was a nation of rifleman. They used their marksmanship skills to cripple Italian command and control on the battlefield by targeting officers, who obligingly identified themselves on the field with big red and blue sashes. Of 610 Italian officers engaged, only 258 survived the battle.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

They “Despise Death”

Emperor Melenik II and his wife Empress Taytu, both played direct roles in the fighting by personally commanding tactical units during the battle. Their bravery was matched or exceeded by that of their common born countrymen who rallied to the cause of defending their shared country to create a diverse, but united army. On the eve of battle, General Baratieri warned his brash generals about the fearlessness and ferocity of Ethiopian warriors. He told them, “they despise death.”

The Ethiopians paid a high price in valorous blood for their victory at Adwa. Though the dead were never counted, it’s estimated that they suffered 10,000 killed and another 7,000 wounded. Depending on whether the army numbered 100,000 or 75,000, those losses represent a casualty rate from 17 to 23 percent. These were heavy losses; but not out of line with what you would expect attacking at a firepower disadvantage to the defender.

Casualty figures vary, but total Italians, losses including their Askari allies, were estimated by contemporary sources at around 6,200 killed and 1,400 wounded with an additional 1,900 Italians and up to 2,000 Askari captured. In total, that represents a loss of from 66 to 76 percent of the total force depending on whether it initially numbered 15,000 or 17,700 men. The Battle of Adwa cost the Italians a third of their troops in Africa.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Rifles Abandoned in Retreat

As Italian units crumbled, survivors fled the battlefield in disarray, abandoning all their artillery and equipment, including 11,000 Model 1870/87 Vetterli-Vitali rifles. Fearsome Omoro cavalry wearing their lion headdresses pursued them for nine miles. The morning of the battle, Emperor Melenik II, knowing that prisoners would be valuable leverage in post-war negotiations, is said to have instructed the Omoro to, “bring me the men, not the testicles.” However, collecting the scrotum of the enemy as a war trophy was an old Ethiopian military tradition.

The underlying rational was that an emasculated enemy could not produce offspring that would come back to fight another day. It’s estimated that 7 percent of the Italians were castrated on the field at Adwa. Most of the Emperor’s men regarded the Eritrean Askari prisoners as traitors and wanted them executed. The Emperor wanted to forgive them but conceded to instead punish them with the amputation of their right hand and left foot.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In the simplest sense, the Ethiopians won the First Italio-Ethiopian War because they had everything they needed to win (politically, ideologically and operationally) and the Italians invaders did not. To his credit, General Baratieri actually realized this, but the pro-colonial interests in Italian government that pulled his strings did not. Worse still, both the government in Rome and his key subordinate officers in the field made the mistake of underestimating the resolve and capabilities of Emperor Melenik II, who laid the foundation for Ethiopian victory years before Adwa.

More War

Emperor Melenik II was too intelligent to not expect an ultimate showdown with one or more European colonial powers. In 1884 Italy had helped him consolidate his power over what amounts to present day Ethiopia by supplying him with 8,000 Vetterli-Vitali Model 1870/87 repeaters in exchange for recognition of their colony in Eritrea. Then, by the primitive subterfuge of altering the text of the Treaty of Wuchale, the Italians “deceived” Melenik II into signing away Ethiopian sovereignty. The Emperor may have been aware of the ruse.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In preparation for war with a European invader, he saw to it that Ethiopian soldiers would be able to meet them with near parity on the battlefield using metallic cartridge rifles rather than muzzleloaders. Thousands and thousands of guns were imported, most of them recently obsolete single shots. Ethiopia has a large Orthodox Christian population. Orthodox Christian Russia supplied them with huge numbers of Berdan single-shot bolt-action rifles. From France came Gras and Chasspot bolt actions. By the time Melenik II annulled the Treaty of Wuchale, giving Italy an excuse to take military action against him, the Ethiopian fighting man had become a much more lethal adversary.

Ethiopian Advantage

Ethiopia also had a significant military advantage in its terrain. It is absurdly mountainous, especially in the North. These mountains were a natural line of defense against Italian attack from the Eritrean coast, exhausted European troops who had to march through them, created nearly insurmountable logistics problems for the Italian Army, and tied down a substantial part of their force for transport and protection of their supply lines. The invading Italian troops suffered for lack of enough food and water, while Ethiopian forces lived off the land with the support of the population.

Europeans called Ethiopia the Switzerland of Africa. The Capital City, Addis Ababa, established by Emperor Melenik II in 1889, is at an elevation of 7,726 feet above sea level, about 2,500 feet higher than Denver, Colorado. Ethiopian peoples who lived in this thin aired region for millennia, could move over its rugged terrain with comparative ease, astonishing speed, and barefoot. They also knew the lay of the land intimately where the Italian commanders were strangers to it and fatally handicapped with inaccurate maps.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Rifle Markings

I know the rifle you see in these photographs wasn’t one of those given to the then King Melenik in 1884 because it was made in the Terni arsenal in 1886. I’ll never know for sure if it was among the 11,000 rifles captured by the Ethiopians at Adwa in 1896, but I’d like to imagine it was.

The stock bears the “AOI” (Africa Orientale Italiana) brand used by the Italian colonial government to mark arms issued to collaborators working in various civilian roles, including a type of rural colonial police during the Second Italio-Ethiopian War from 1935-1936. The rifle could have been brought over from Italy then to use in the African colonies, though it seems odd to me that such an old model would still be around, unmodified, in an Italian arsenal on the eve of World War Two. There were two unusual things I noticed about this particular rifle that made me think it was in Ethiopia a long time before 1935 and perhaps owned by a serious marksman.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

First, its rear sight has been missing a long time, and second it has an unusually light and crisp trigger pull that would surely have helped the shooter place his shots with greater precision. Was the sight damaged and the rifle turned in by an Ethiopian soldier long ago for repair, only to sit unmolested until it was captured at the arsenal during a second Italian invasion and put it into service once more? It’s fun to ponder the history it’s been witness too, whether I can confirm it or not.