You’ve probably heard the phrase “The best laid schemes of mice and men often go awry.” Well, if you substitute “rats” for “mice,” you’ll have described a three-year federal law enforcement operation that was shakily conceived, carelessly wrought and at times fueled by less-than-noble motives. It would spell disaster for all involved. Comprising Operation Wide Receiver and Operation Fast and Furious, it was officially known as Project Gunrunner and run by the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATFE).

Project Gunrunner

It was sold as an intelligence-gathering sting to track and hopefully stop the flow of weapons into the hands of criminal traffickers and on to Mexican drug cartels. This was not a faulty idea in itself, but it allowed, even encouraged, thousands of guns to be illegally sold to traffickers on the premise that they could be tracked through higher and higher levels and ultimately to major players in the drug cartels of Mexico.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But as author Mike Detty — personally involved in Project Gunrunner — writes in his account, Guns Across the Border, “At last I understood the ugly truth. All of the risks I took, all of the work I performed, all of the man hours and resources poured into this case by the ATF were not to take down a cartel. In my opinion, the reason that guns were allowed to cross the border in Wide Receiver as well as Fast and Furious was to have American guns show up at Mexican crime scenes.

“With American guns being used in ruthless savagery across the border, a push could be made for a new assault weapons ban here in the United States. There is no other explanation why guns would be continually allowed to cross the border after the purchasers, their cartels and ports of entry had already been identified.”

Failed Cooperation

Most federal agencies, at least in the law enforcement arena, do a necessary, often crucial, job. A majority of employees and agents are competent and ethical, and not infrequently heroic. Most individuals and businessmen who are in an arena regulated or policed by a given agency are on the same sheet of music. They do not want to break the law, nor are they inclined to help those who do.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As long as everybody wears white hats, agency-industry cooperation can be an effective tool. A tool for putting the bad guys out of business. However, that is not always the case. If the competence and ethics of government apparatchiks in upper management ever falter, especially up in the lofty realm of political appointees, then an operation can go sour and have an effect opposite its original rationale.

Operation Wide Receiver, and other “gun-walking” schemes like it, depended on active cooperation with border-state gun dealers. Typically, those proving pivotally valuable information were engaged by federal law enforcement as confidential informants. This is because of their spotless records and personal reputations for strong business and legal ethics.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Sleazy dealers trying to curry themselves out of legal problems are seldom competent, and almost never honest nor reliable. Conversely, as we see from Detty’s carefully documented experience, not all agencies and agents are wonderfully ethical, honest or reliable, either. They do not bury their own dead. They can turn on those who have helped them at considerable personal risk if they think some official malfeasance or incompetence is about to be revealed. Throw a civic-minded volunteer under the bus? Of course. But sometimes they like to douse them with gas and set them on fire first.

The Price for Doing Right

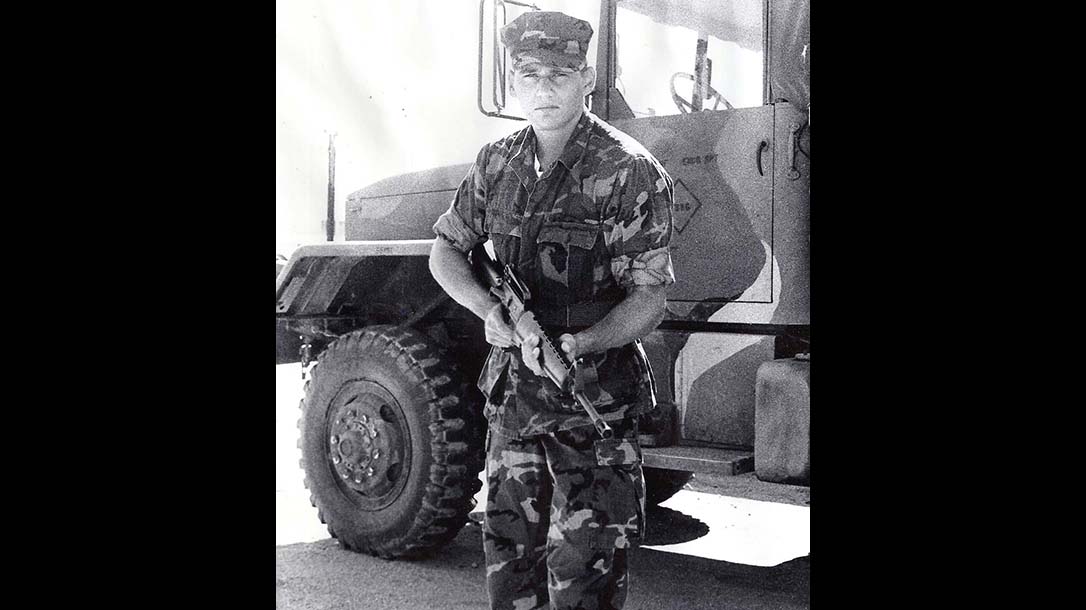

This was the situation of Tucson FFL dealer and well-known outdoor journalist Mike Detty. He alerted the local BATFE after he was approached by persons he suspected were trying to make straw-man buys for the cartels, 50 units at a pop.

Detty assumed considerable personal risk working undercover to help the government make a case against these criminal traffickers. He even sold great quantities of designated guns out of his own home in the dark of night. This was at the direction of the BATFE, which was filming and taping it all.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Agents told him the investigation, and his stint undercover, would last just weeks. However, as it turned out, the case and his involvement would last for three years.

Although Detty never solicited a dime, he was promised hefty rewards, which, of course, were never paid. This particular case took many a turn. The final twist being when Detty’s good intentions, his actions at his own peril just because it was the right thing to do, were rewarded with betrayal by the very agency on whose behalf he had risked so much.

“The positive feedback that I received from Lopez and the other agents was all I needed to push myself a little harder. I followed orders like a good Marine and never lost sight of our goal to topple a powerful cartel—even if it meant placing my personal welfare secondary to accomplishing our mission,” Detty recalled.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

He was told by the BATFE agent he primarily worked with, “Mike, I just wanted you to know that we could have never made it this far without your help. It isn’t often that we let a civilian get this deep into an operation or have an investigation last this long. Everyone in this office appreciates your hard work.”

“It seems like this case is going on forever, and it’s still not over,” Detty said to the BATFE agent. His facial expression changed, and he looked down at his desk. Detty could tell that he wanted to be serious. “Mike I want to tell you that we appreciate everything that you’ve done for us. I know that sometimes we go too long in saying this, but there is not one agent in this office, one person in the Tucson Police Department that has been involved with this case and the agency itself that doesn’t appreciate and admire what you have done. Without sounding Pollyanna, I can tell you that everyone respects you for the danger that you’ve placed yourself in and the way that you’ve handled yourself throughout this case. You have earned the respect of veteran agents, me and the bureau, too.”

At the time, Detty thought the agent was sincere. Maybe he was at that time.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

From Asset to Threat

But as it turned out, talk was cheap. Moreover, any expressed gratitude or admiration did not entail any individual loyalty. The “Confidential” part of “Confidential Informant” could be a whimsical thing.

Loyalty, it turned out, was not a two-way street between the Department of Justice and a public-spirited citizen who had volunteered, and worked for years at personal risk, to do the right thing.

“I learned that the ATF’s public information officer in Phoenix gave my name and contact information to a New York Times reporter who was inspired to write an article after Attorney General Eric Holder’s speech of Feb. 2, 2009, in which he detailed that Mexicans were being killed with American guns and that he and President Obama would like to see the Assault Weapons Ban reinstated,” Detty said. “If it wasn’t bad enough that Department of Justice employees were exposing me as an informant, now an ATF agent was doing the same thing.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

To keep the facts straight, from early on Detty had kept a private journal. Government minions learned of it. They apparently feared it could be a source of embarrassment or worse—in passing it detailed several official misadventures.

From that point on, Detty was cast into a limbo somewhere between persona non grata and outright threat. His personal e-files were hacked and redacted by persons unknown, but of course there were backups. Detty does not make this observation. But it begs: if a former intelligence asset now has the potential to be a liability or embarrassment, how better to solve the problem than to let the cartels he was working against know who he is and let nature take its course?

“All of my life I had nothing but the greatest respect for federal agents and those who work in the Department of Justice. Now for the first time I was seeing them for what they were—lazy, sloppy, self-protecting civil servants who cared more about self-preservation and collecting a paycheck than for doing the right thing. The high regard I once had for these people had been replaced with contempt. I had gone from one who was extremely proud of my involvement in helping federal law enforcement to someone who was ashamed and embarrassed. I felt betrayed and disgusted,” Detty concludes after describing the agency’s subsequent treatment of him.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Not that Detty’s shameful treatment caused any shame within the agency: BATFE Deputy Director Kenneth Melson regaled the House Committee on Appropriations with stories of the success of one of Detty’s cases. Of course, he failed to mention that the CI who brought them this case was publicly outed by an assistant U.S. attorney, or that they never paid him the reward. Again, he did not solicit the reward, but was originally promised and due.

Detty’s insightful analysis of the “gun-walker” operations is simple: “It took me three years to learn the truth … The ATF had screwed up badly and had based an entire operation on lies to the AUSA. Their arrogance and assumption that [the AUSA] would go along with their deception caused them to lose years of man hours, resources, money and, most importantly, credibility.”

The BATFE inspector’s general’s office, relying at times on Detty’s notes, did an investigation. It, typically, did not go very far upward. Perhaps the investigation should have been done by the General Accounting Office. Maybe they would have balanced the overall cost against the result: The tally would show a handful of low-level results. Make that a handful and one, to include a federal officer killed by one of the illegally purchased guns knowingly put in the hands of criminals by the BATFE.

A reliable CI is a priceless investigative tool. Especially one who is his own man because he is not helping just to save his own hide or doing it for the money, but acts with the same intent as a volunteer fireman, risking a great deal just because it’s the right thing to do. The training manuals call this sort of valuable tool an intelligence asset. Any good asset needs to be properly taken care of. This is the same as protecting an irreplaceable piece of electronic gear from the elements. But Mike Detty was an asset that federal law enforcement abused, used up and threw away.

‘Guns Across the Border’ — The Account of Project Gunrunner

Few novels are as good a read. More so, few documentaries are as carefully written. Between the action and intrigue, there are some bold points to be made here. But the author simply lays out the facts of what comes down with candor and color; and the facts speak for themselves. Because of governmental ineptitude, possibly even malfeasance, a meager few indictments were made from these operations. The facts in this book, however, comprise a further damning indictment of one of our most important federal law-enforcement agencies—from street level to the attorney general’s office.

Good citizens will still be driven to do the right thing. But based on the experiences of Mike Detty, you might want to be careful who you do it for. “Guns Across the Border” is a book not to miss. For more information, visit SkyhorsePublishing.com.

This story is from the spring 2017 issue of Ballistic Magazine. To subscribe, please visit OutdoorGroupStore.com.