One of the greatest “disconnects” in firearms training has to do with defending against close-quarters attacks. Unless you are a duty-bound “authorized perpetrator” (a term borrowed from my friend Kelly McCann), you can’t just shoot everybody. As such, much of what is commonly taught regarding close-range gunfighting doesn’t make sense. For example, drawing a pistol during a close-quarters engagement.

Drawing a Pistol and Safely Getting it Into the Fight

Case in point: The Speed Rock. This technique has been around since the 1970s and is a mainstay of many defensive shooting programs. For advocates of those programs, it’s also the first line of defense against attacks with contact-distance weapons.

In simple terms, it goes like this. The instant you perceive a lethal threat, you grip your holstered pistol, lean back, draw, and fire. To avoid shooting your non-weapon hand, you typically place it behind your head.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

When practiced on the range against a cardboard target, the Speed Rock works great. You shoot when you want to, not when you need to, and your non-gun hand is well out of the way. It doesn’t even matter that you’re off balance since the cardboard won’t hit or stab you. Best of all, your attacker is always “stopped” instantly.

Reality Check

In a real self-defense situation—like a typical knife attack—the theory of the Speed Rock falls apart pretty fast. First of all, your first indication that it’s a lethal-force event is probably the attack itself. With a knife, that most often takes the form of a stab to the torso.

Typically, the assailant will not brandish the knife or announce his intent before attacking. Your job is, therefore, to recognize the attack, instantly identify it as a lethal-force threat, draw, and shoot. You also must do all that before the knife makes contact.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Curiously, if you do the technique “right,” you’re supposed to lean back and purposely raise your non-gun hand out of the way. That purposely leaves your torso completely unprotected and actually increases the likelihood you’ll get stabbed.

Assuming you’re actually able to pull all this off and land accurate shots, there’s still no guarantee you’re safe. Just because the attacker is shot doesn’t mean he bursts into flames and stops stabbing immediately. Handgun stopping power is notoriously unpredictable. And the closer you are to the threat, the more danger that uncertainty poses.

This, Then That

Statistically, most potentially lethal attacks occur at close range—specifically 0-10 feet. At those ranges, physical contact with the attacker is extremely likely. If he is armed with a contact-distance weapon like a knife or club, it’s almost inevitable. With that probability in mind, protecting yourself from serious injury—not drawing your gun—should be your highest priority.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

If the environment allows it, movement is certainly a good thing—provided you’ve trained to draw and shoot while moving. However, if you can’t determine he’s armed from a distance or if he attacks in a confined area, movement won’t help. In fact, the gun won’t even help—yet.

You need to use unarmed skills to block the attack and, ideally, hurt your assailant before drawing a pistol. In essence, you’re earning your ability to draw with your empty-hand defensive skills.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

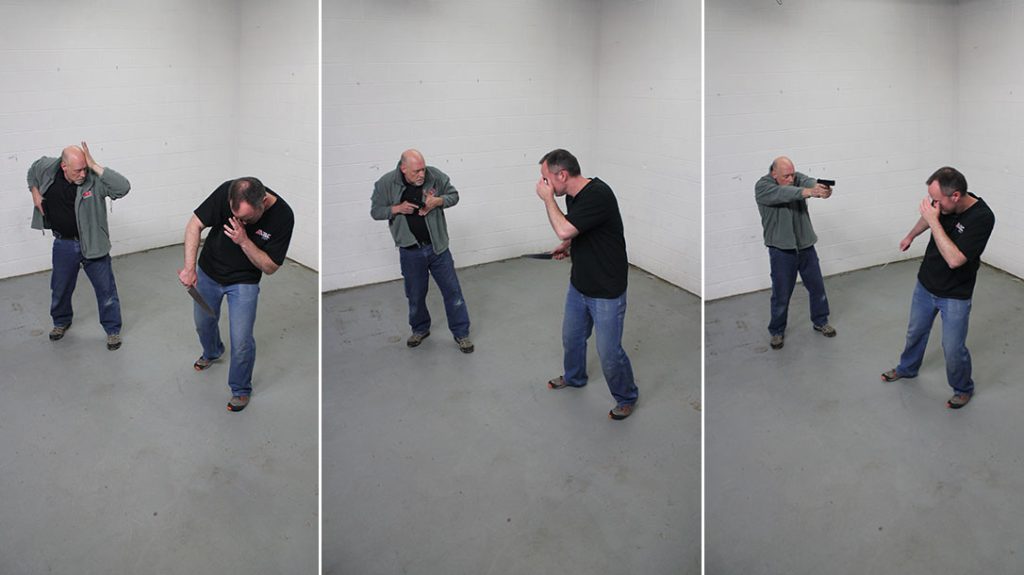

Against the aforementioned knife attack, your first priority should be to not get stabbed. A strong, two-handed block consistent with the body’s instinctive startle response is a good place to start. From there, execute an immediate counter that debilitates your attacker at least momentarily.

Eye strikes are ideal for this since they require little force but have a profound effect. With you uninjured and your attacker stunned, you now have the time to draw your gun. If the environment permits it, you may even be able to move to create distance as well.

The Guarded Draw

Most commonly taught drawstrokes condition you to achieve a grip on the holstered gun while positioning your support hand in front of your abdomen. That way, once the gun is drawn, your hands can come together safely in a two-handed grip before extending toward the target.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

From a square-range gun safety perspective or against an attacker at a significant distance, that works great. Against a close-range threat, however, it’s better to keep yourself protected as you draw.

The “Guarded Draw” achieves all the same positive things as a Speed Rock but keeps you much safer. The key components of it are the non-gun hand/arm and the ability to draw one-handed.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

From a right-handed perspective, first, bend your left arm, so the angle between the forearm and elbow is 90 degrees. Pivoting your arm at the shoulder, raise the pre-bent structure on a vertical plane. Keep your left hand open and your fingers extended.

At the top of the arc of motion, your left palm should come to rest on your forehead just above your left eyebrow. Your palm should anchor solidly to your forehead to create a solid triangle of shoulder, elbow, and head.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Bending the elbow before you raise your arm is important because it creates a strong protective structure quickly. Even before your palm reaches your forehead, the structure of the forearm is protecting your head and neck. If you wear glasses, this movement also allows your hand to naturally index above them.

Drawing the Pistol

At the same time, your left hand is establishing its guard, your right hand should also be moving. Specifically, it should bend at the elbow to about 90 degrees. As your left-hand rises and your left shoulder naturally rotates forward, your right shoulder should rotate back.

This simultaneous rotation of the shoulders allows the right hand, with fingers curled into a natural hook, to clear your cover garment. If you’re wearing an open-front jacket, it clears horizontally to the rear. If you have a closed-front garment, it should clear up and back.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

At the end of the clearing motion, use your inner wrist to pin the material against your body. Then drive your hand straight down to grip the gun. With a master grip established, raise your right elbow to lift the gun out of the holster. Finally, drop your right elbow to pivot the muzzle forward.

You are now in a solid weapon-retention position, with your head and neck protected by the structure of your left arm. With your left palm indexed against your forehead, your left elbow is up and well away from the muzzle. At close range, you can safely fire at anything below shoulder level.

If you’re far enough away to shoot from an extended position, bring your left hand to your chest first. Slap your chest to physically index your hand away from the muzzle. Then bring your hands together into a two-handed shooting position.

Drawing a pistol at close quarters begins with not dying. Protect yourself first, earn your draw, and keep your guard up.