Incident 1: A dope dealer from Detroit arrives at a Midwestern city to sling his crack cocaine. Arrested for warrants and assault on a police officer, he is handcuffed and searched prior to being loaded into a police transport wagon and taken to the local jail. After removing the handcuffs, the deputy sheriff working the booking area of the jail conducts a detailed search and detects a pocket the doper had sewn into his boxer shorts, between the legs. In this pocket, the deputy finds a fully loaded semi-auto handgun.

- RELATED STORY: Anatomy of a Gunfight: Surviving a Shootout

Incident 2: A subject resists being arrested for receiving stolen property after he stops while astride a stolen motorcycle. Pepper sprayed and handcuffed behind his back by two officers, he is placed into the backseat of a police SUV. An officer attempts a cursory pat-down but does not complete the search. Once alone in the backseat, the suspect quickly moves his handcuffed hands under his feet to the front of his body and accesses a small handgun in his left front pants pocket. Firing through a rear window, the suspect dives out. Now armed and presenting a deadly threat, the felon attempts to flee and is quickly shot by the officers.

Incident 3: A suspect is arrested after a shooting on a public street. Arrested and handcuffed behind his back, he is transported to the police station and placed in the detective bureau holding room, where his handcuffs are removed. As soon as the detective walks away, the suspect reaches into his front waistband and pulls out a full-sized 1911, cocks the hammer and fires a bullet into his own head. The detective walks back into the room and says, “Nobody shook him.” In other words, no officer searched the suspect.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

All three incidents ended with officers completing the number one rule of law enforcement: making it home at the end of their shift. But in all three, it was accomplished only by luck. Had the armed men decided another course of action, officers could have easily been killed.

Follow The Rules

There are some basic rules of frisking and searching you must follow:

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

- If the suspect is under arrest, handcuff them first, then search them.

- Search the suspect like your life depends on it, because it does.

- Don’t be sloppy. Sloppy searches can and do kill law enforcement officer.

- Live by the “plus one” rule: If you find one weapon or piece of contraband, always search for more. There is always one more thing you’re missing.

Officers cannot pat down or frisk every suspect they come into contact with on the street. A “Terry stop,” as defined by the courts, is based on articulable, reasonable suspicion that a crime has been, is being or is about to be committed, and that the suspect is involved. Based on reasonable suspicion, the suspect can be forcefully detained if they do not voluntarily comply. During a Terry stop, a Terry frisk—a pat-down of only the outer garments for weapons—may be necessary based on the totality of the circumstances if the officer comes to believe that the suspect may have a weapon on his or her person. During a Terry frisk, an officer cannot insert his hand into pockets or rearrange exterior clothing unless something is observed or felt which may be a weapon.

If the officer asks for and receives consent to search from the suspect, even if he has reasonable suspicion to conduct a Terry frisk, the officer can reach into pockets and search inside outer garments, such as coats or jackets, as long as he does not venture into strip searching (looking into or rearranging undergarments such as brassieres and clothing covering the genitals or breasts).

In some cases, such as confronting suspects believed to have shot someone or reported to be a suspect in a crime of violence like an armed robbery, the suspects may be challenged by officers at gunpoint, handcuffed and then patted down for weapons (a Terry frisk).

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

If during a Terry frisk or a search with consent an officer sees or feels a weapon or piece of contraband concealed or partially concealed, they should alert other officers, handcuff the suspect and then retrieve the evidence. If, for instance, an officer is conducting a search with consent and feels what he believes is a gun, even if the handgun is inside the suspect’s boxer shorts in actions which would otherwise be known as a strip search, exigent circumstances exist to handcuff them and then retrieve and secure the gun. If a bag of contraband, such as crack cocaine, is felt in the crack of the suspect’s buttocks or in their groin area, the suspect should be handcuffed and a strip search authorization received from a supervisor prior to retrieval. A strip search is not a cavity search, which can only be conducted by a physician or proper medical personnel. (Note: State laws differ when it comes to strip searches. Officers are advised to contact their police legal advisors for specific legal advice and direction.)

Control Techniques

While conducting Terry frisks or searches with consent, stay away from “prop searches,” where suspects are advised to “assume the position” and put their hands on the trunk, hood or roof of a vehicle, or on a wall, and the officer pats them down with little to no control. Wall or prop searches actually afford the suspect more stability or “base” than that of the officer. Placed in this position, a suspect can escape or attack simply by grabbing the officer’s hand and turning violently, pitching the lawman into the wall or car.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Two techniques offer more control than the outdated prop search.

1. Fingers interlaced behind the head: In this technique the suspect is ordered to place their hands behind their head and interlace their fingers. They are told to spread their legs and point their toes to the outside. Once the officer grabs control of the fingers, the suspect is off-balance to the rear. Starting at the head and overlapping to each side of their midline, the suspect’s clothing is first observed for obvious threats, such as knives or other threats like hypodermic needles, and then grabbed and twisted. If you feel something in the pocket, ask what it is before reaching in with your hand. To transition to the other side, the officer just re-grips the suspect’s fingers.

The greatest risk to officers using this technique is the suspect’s ability to turn or pivot even with their fingers tightly held by the officer. This is more easily accomplished if the suspect is allowed to stand upright and maintain their balance.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

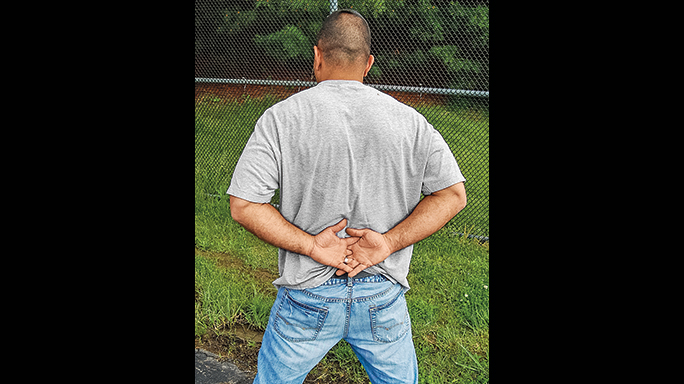

2. Fingers interlaced behind the back: In this technique the suspect is ordered to interlace his fingers behind his back and rotate his hands so the palms are outward. The officer grasps the suspect’s hands, with specific control of the pinky finger. Because the suspect’s shoulders and elbows are locked, they lose leverage and most of their ability to spread their fingers.

This frisking and handcuffing style offers more control than having the suspect’s fingers interlaced behind their head, but it’s more complicated, requires more practice to maintain proficiency and is more difficult to maneuver a suspect into the proper position.

In both techniques, particular attention is paid to those areas where weapons and contraband are normally secreted: the appendix, groin and buttocks.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

When and if a weapon or piece of contraband is detected, probable cause has been developed to warrant an arrest. The suspect should be handcuffed first and then the weapon or other evidence retrieved.

Prevent Fatal Errors

To protect the officer from bodily fluids or other risks (i.e., body lice), officers may elect to wear latex gloves to protect themselves. This may result in a loss of finger sensitivity during the search. Leather, synthetic or Kevlar-lined searching gloves inhibit an officer’s ability to feel through a suspect’s clothing and more easily detect contraband. Having hand sanitizer in your patrol bag is a good idea.

- RELATED STORY: 9 Cases That Show How LEOs Can Stop Ambush Killers

Learn sound searching tactics and techniques and apply them on the streets on a daily basis. There are bad guys and gals concealing illegal guns, drugs and other contraband on our streets. It’s our job to locate, identify, frisk and arrest them—let’s just do it as safely as possible.