An impartial review of the dynamics of stopping mass murder shows that the NRA’s Wayne LaPierre was right when he famously said that it takes a good guy with a gun to stop a bad guy with a gun. We see this in case after case. But what happens when the armed good guy who stopped the bad guy is then mistaken for the bad guy and shot by police? To analyze that, let’s discuss three such recent tragedies.

Home Invasion

Case One takes us to Aurora, Colorado, in July of 2018. An apparently deranged man named Dajon Harper, 26, broke into a residence and decided to take a shower in the occupied home. However, an 11-year-old boy who lived there was awakened by the sound. As he approached the bathroom, the intruder saw him, grabbed him and attempted to strangle him.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The boy’s grandfather — Richard “Gary” Black, 73 — heard the boy’s screams and ran to his assistance, pistol in hand. When he saw a nude adult male trying to kill his young grandson, Black shot the attacker twice, killing him. The autopsy toxicology screening later showed that the home invader was high on drugs, including meth.

Police arrived to find a chaotic scene. As responding officers entered the home, they saw Black with a gun in one hand and a flashlight in the other. The officers shouted commands to drop the gun, but when Black turned towards them, still armed, officers fired. Tragically, moments after saving his grandson’s life, Black died from his wounds.

The slain hero was a Vietnam combat veteran whose battle experience had left him extremely hard of hearing. Many people now believe that he was unable to hear the police commands to drop his gun.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

A few months later, Fox News in Denver reported, “Adams County District Attorney Dave Young described Richard ‘Gary’ Black’s death as a ‘harrowing tragedy’ but said his role was to determine whether the Aurora police officer who shot the 73-year-old Vietnam War veteran was justified in using deadly force. Based on witness interviews and more than 90 videos captured by officers’ body cameras, Young said Officer Drew Limbaugh did not know who Black was and fired when the homeowner refused police commands to drop his handgun. Young said Limbaugh’s belief was reasonable, and prosecutors cannot prove that the officer was not justified in firing. He said there also is no evidence that Limbaugh was reckless or criminally negligent. ‘Officer Limbaugh engaged in conduct that was consciously focused on minimizing the risk to public safety,’ Young wrote.”

More Situations

Case Two occurred in the suburbs of Chicago in November of 2018. A man entered a bar and opened fire, injuring multiple customers. A 26-year-old security guard, Jemel Roberson, shot the man, ending the terror. Roberson then knelt on the back of the fallen gunman and held his pistol on him. But when police arrived, one officer opened fire, fatally wounding the young hero.

At the time of this writing, there are conflicting accounts of exactly what happened. Some of Roberson’s friends and coworkers insist that he had on a cap marked “security” when police shot him. They also say multiple witnesses shouted that Roberson was a guard. However, the investigating agency, the Illinois State Police, stated, “According to witness statements, the Midlothian officer gave the armed subject (Roberson) multiple verbal commands to drop the gun and get on the ground before ultimately discharging his weapon and striking the subject.” The family of the deceased hero has filed a lawsuit over the incident, which is still under investigation.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Case Three took place on February 14, 2018 — the same day an infamous mass murder took place at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. In Amarillo, Texas, a gunman entered the Faith Hill Mission and took some 100 people hostage. An ex-con in the chapel named Tony Garces jumped the man, grappled with him and successfully disarmed him. However, responding Amarillo cops arrived to find Garces holding the gun, and shouted at him to drop it. When he began to lower the gun instead, they opened fire, wounding Garces twice.

Garces claimed that he didn’t want to drop the gun for fear it would go off; he was attempting to set it safely on the floor when he was shot. Police, however, only saw an active killer disobeying commands to drop the gun. Joshua Jones, 35, the actual gunman, is in custody. Garces has taken legal action.

Learning Points for Good Guy With a Gun

Examine the commonalities in the above cases. All three times, the good guys who were shot — two of them fatally — were heroes who had risked their lives to save others and undoubtedly saved multiple lives. All three times, police were going in on a call that was essentially “man with a gun, there now, likely to murder many,” and the heroes were each “holding a gun, there now.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In all three cases, police shouted commands to drop the gun, but the people didn’t follow those commands. On the law enforcement side, police officers have to remember that in chaotic situations like these, factors such as auditory exclusion and loud background noise can render the good guy with the gun unable to hear commands. When shots fire, everyone involved can have impaired hearing. Or, as Case One shows, a subject might be deaf to begin with, further complicating matters.

On the “good guy with a gun” side, it must be remembered that law enforcement officers are taught that in such situations the identified officer’s commands must be instantly obeyed. Because “blue on blue” mistaken-identity shootings almost always involve plainclothes/undercover/off-duty cops shot by uniformed officers, responding police see these as the rules of engagement and expect the non-identifiable armed person to drop their weapon upon command. This means you should carry a gun that is “drop safe” and designed to be immune from inertial discharges due to impact. And if you have taken the bad guy’s unfamiliar gun, you’re better off risking an unintentional discharge from dropping it than being shot by police, as Case Three proves.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

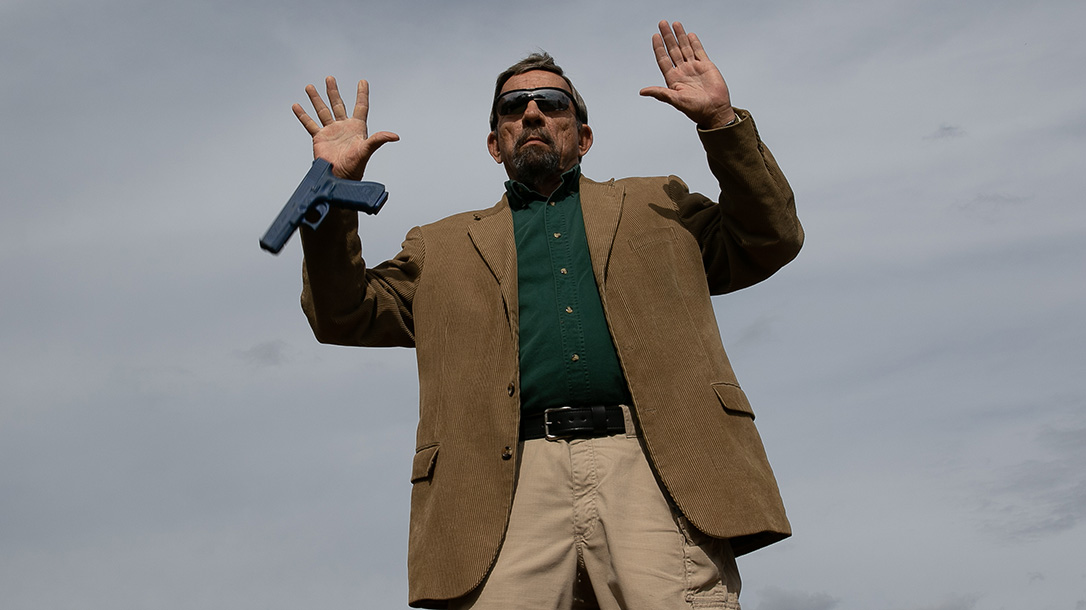

If you are present at a mass murder, don’t draw your gun until you have positively identified the threat. Also, as soon as you have neutralized the threat, holster the weapon. All the other good guys with guns, including other armed citizens or plainclothes officers, are likely to see “person with gun” as a threat, not a rescuer. Remember that when police shout orders, human nature may make you turn toward that sudden sound. This means the gun will turn with you, mimicking an attempt to shoot the officer. Open your fingers to make it clear you are not taking a shooting posture; let the weapon fall upon the “drop the gun” command.

George Santayana famously said that those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. That advice is particularly relevant in this situation. Let us all work to make sure the tragic outcomes of the heroic rescuers outlined here do not occur again.

This article was originally published in Combat Handguns July/August 2019. To order a copy, please visit outdoorgroupstore.com.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below