In terms of military power and prowess, Germany and Japan were far more potent than the U.S. and its Allies when the U.S. entered WWII following the attack on Pearl Harbor. That the Allies were able to defeat the Axis is a testament to the cunning and strategic skill of the generals who devised and directed the war efforts in Africa, Europe, and the Pacific.

- RELATED STORY: WWII Veteran Profile: The Greatest Generation’s Nick Reid

As Army Chief of Staff, Gen. George Marshall not only developed the overall war strategy for the Allies, he also selected the generals to carry out his plans. Called the “Organizer of Victory” by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Marshall modernized the Army and organized the largest military expansion in U.S. history. Because of Marshall’s ability to work with Congress and his value as a war planner, President Franklin Roosevelt opted to keep him in Washington and instead named Dwight Eisenhower the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe in December 1943. In recognition of his wartime successes, Marshall was promoted to General of the Army on December 16, 1944, becoming the first U.S. Army officer to achieve the rank of five-star general. Following the war, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for the Marshall Plan, a strategy to help Europe rebuild.

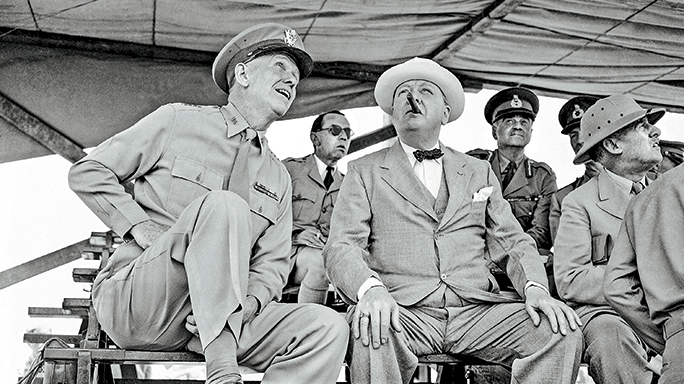

In many ways, Dwight Eisenhower was the ideal combination of diplomat and strategist, both traits equally useful in overseeing execution of the war in Europe. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower joined the General Staff in Washington and helped devise plans for defeating Germany and Japan. He directed Operation Torch, driving the Axis forces out of North Africa, then led the invasion of Sicily and early stages of the advance through Italy. After being named Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, Eisenhower planned and directed the invasion of Normandy, and his temperament and style were well-suited to handling difficult Allied leaders such as Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaulle. After directing the Allied march across Europe and into Germany, he coordinated with the commanders of Soviet forces for the final defeat of the Germans. Greeted as a hero upon his return to the U.S., Eisenhower served as Army Chief of Staff, was named president of Columbia University, and in 1952 was elected to the first of two terms as President of the United States.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Gen. Omar Bradley may have been “quiet, unassuming, capable,” as described by Marshall, but he was also efficient and, when needed, ruthless. In one of his first wartime command assignments, he turned the demoralized 28th Division into a feared fighting unit. He helped Eisenhower out of several scrapes in Africa, then commanded the Second Corps in both Tunisia and Sicily. He later commanded the First Army in the invasion of Normandy, and was the architect of Operation Cobra, which established a corridor into Brittany and planned the breakout from the Normandy beachhead. By V.E. Day, Bradley was in command of more troops (1.3 million) than any general in U.S. history. Eisenhower called Bradley the “master tactician of our forces,” and President Harry Truman labeled him the “ablest field general the U.S. ever had.”

Gen. George Patton is one of the most celebrated commanders of WWII, renowned as much for aggressiveness, misdeeds, and controversial statements as for tactical brilliance. When he landed in North Africa in 1942 as head of the U.S. force, he told the troops:

“We shall attack and attack until we are exhausted, then we shall attack again.” He put demoralized U.S. forces back on the offensive and commanded the victory at the Battle of El Guettar in Tunisia in March 1943, giving the U.S. its first major victory against Nazi forces. Known by his troops as “Old Blood and Guts,” Patton led the invasion of Sicily, but caused lasting damage to his reputation when he slapped a shell-shocked soldier and accused him of cowardice. Following a suspension of duty, Patton staged a phantom invasion of France while the Allies landed at Normandy, then pushed his 3rd Army across France and into Germany in pursuit of Nazi forces. In early 1945, he led his army across the Rhine and captured 10,000 miles of territory, helping to secure victory over the Nazis.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

- RELATED STORY: Classic Aircraft: Top 12 World War II Dogfighters

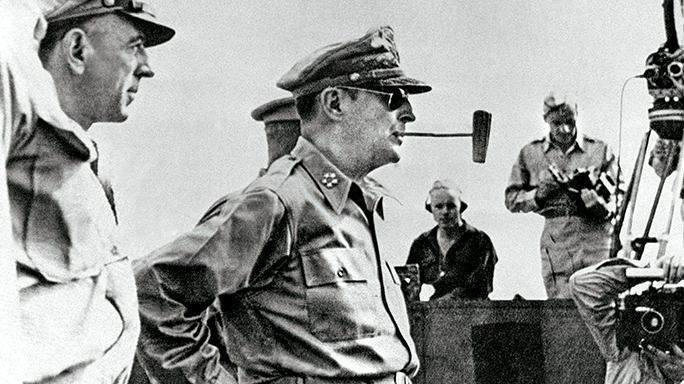

Gen. Douglas MacArthur was 60 years old and retired from the Army in July 1941. But with Japan rattling sabers of war, MacArthur was recalled to active duty and named commander of U.S. Army forces in the Far East, thanks to extensive past work with the Philippine military. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese staged a surprise assault on the Philippines, destroying MacArthur’s air force and compelling MacArthur and a select group of family and officers to flee to Australia. Marshall awarded MacArthur the Medal of Honor, not for acts of valor, but to “offset any propaganda by the enemy directed at his leaving his command.” MacArthur developed a campaign of island-hopping, attacking Japan at key strongpoints, and in 1944 he returned to the Philippines after defeating the Japanese at Iwo Jima and Okinawa. As Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Pacific, MacArthur accepted the Japanese surrender aboard the USS Missouri. He was later put in command of the U.N. forces after North Korea invaded South Korea, but he was relieved of duty after publicly criticizing the policies of President Harry Truman.

This article was originally published in the WORLD WAR II VICTORY™ 2015 issue. Subscription is available in print and digital editions here.