One of the better-known U.S. military weapons of all time is the “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1903.” It is considered by many to be the epitome of the bolt-action military rifle and proved its versatility in two World Wars. As a few examples of this versatility, in addition to the standard infantry rifle variant, ’03s were used, among other duties, as sniper rifles, trench periscope rifles and grenade-launching platforms.

- RELATED STORY: M1903 Springfield Bolt Action Combat Rifle

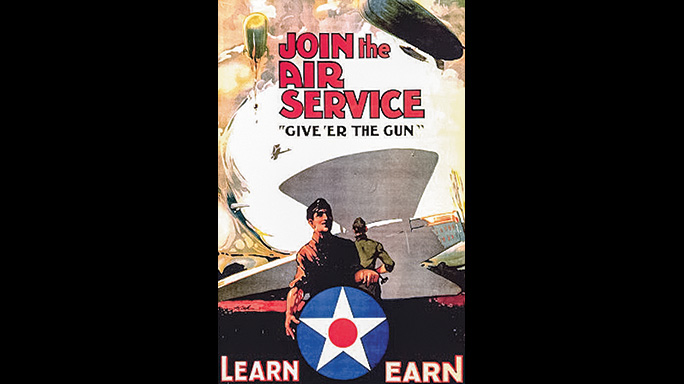

During World War I, an extremely interesting and little-known variant of the M1903 was modified for use by the fledging U.S. Army Air Service. Generally referred today to as the “Air Service ’03,” the rifle was basically a standard M1903 service rifle with a specially shortened stock and handguard, a simplified rear sight and a 25-round extension magazine. It was clear from Ordnance documents of the era that the weapon was not intended for infantry use, as it was described as being “stripped for Air Service.” Although genuine examples are very rarely seen today, the existence of the weapon has been well known for a number of years. What is not so well known, however, is the actual purpose for which the weapon was designed. Clearly, it was to have some application for the Army’s Air Service, but documentation from the era does not specify the exact use for which the gun was intended.

.30-06 Stowaway

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Several theories have been advanced. The most common seems to be that the weapon was intended for use by personnel manning the observation balloons that were commonly employed in WWI for artillery spotting and monitoring troop movements. It has also been opined that the guns were to be utilized as defensive armament for two-seat observation/scouting aircraft. Still another theory postulates that the rifles were intended to be carried in an aircraft in the event a pilot was forced down behind enemy lines (not an uncommon occurrence) and needed a weapon more effective than a handgun for self-defense.

After considering the relative merits of these theories, the latter would seem to be the most likely. The usefulness of a bolt-action rifle against enemy aircraft while firing from the unstable platform of a swaying balloon basket appears to be quite implausible. Likewise, a manually operated rifle would hardly be a suitable weapon with which to counter enemy fighters armed with multiple machine guns. It would seem that both of these theories fly in the face of logic. Thus, almost by default, the utilization of a modified bolt-action service rifle by a downed pilot seems to be a much more persuasive argument.

Since a pilot would not be equipped with a cartridge belt, the 25-round extension magazine would provide a reasonable supply of ammunition self-contained in the rifle and ready for immediate use. The cut-down stock and handguard, the elimination of the sling swivels and other modifications would result in a slightly lighter weapon, which was a useful attribute in the airplanes of the day when every ounce of extra weight counted.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

This speculation is supported by several Ordnance Department documents of the era, including the original Springfield Armory blueprints, which refer to the weapon as “U.S. Rifle, Model of 1903, Altered for Aircraft use.” Another document pertaining to the gun’s 25-round extension magazine revealed that the component was expected to be adopted “for aeroplane…use.” Such documents would seem to refute the balloon-armament hypothesis since balloons were not typically referred to in such a context as either “aeroplanes” or “aircraft”

during that time.

On March 13, 1918, the Ordnance Department requested that a prototype of the proposed weapon be fabricated at Springfield and sent to Washington, D.C., to be subsequently forwarded to France for testing under “combat conditions.” A memo dated the following day ordered Springfield Armory to determine the time necessary to build 2,000 rifles of this type. On April 29, 1918, Ordnance documents confirm that the requested prototype Air Service ’03 Rifle was delivered to Col. H.H. Arnold (later General “Hap” Arnold of World War II fame). Subsequent documents reveal that General John Pershing requested that 825 “Air Service” rifles be sent to France for use by the Allied Expeditionary Force by June 1, 1918.

It is confirmed that the U.S. Army Signal Corps Control Board con-

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

vened in June of 1918 to evaluate the proposed weapon and suggest any necessary modifications. It might seem odd that the Signal Corps was the recipient of the prototype rifle, but, at the time, it was the entity responsible for procurement of aircraft and related equipment. The board proposed a few minor modifications, chiefly pertaining to the rear sight. The suggestions were approved by Ordnance and Springfield Armory was directed to begin manufacture of the weapon.

Frontline Testing

The Air Service ’03 utilized the same receiver, barrel, bolt and front sight as the standard M1903 rifle. Original Air Service rifles have been observed with serial numbers ranging between “856709” and “862069,” but numbers

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

in close proximity on either side of this range could be possible. Barrels were marked “SA” with the Ordnance “flaming bomb” insignia and dated from early to mid-1918.

The stock, handguard and barrel band were purpose-made by Springfield Armory and were not simply modified standard ’03 components. The solid (not split) barrel band was secured by a single woodscrew. A standard ’03 service rifle M1905 rear sight was altered by cutting down the sight leaf, modifying the sighting notch and permanently setting the drift slide at the 100-yard increment by means of a machine screw inserted through the peephole.

The 25-round extension magazine prototype was manufactured by the National Blank Book Company. The magazine assembly replaced the standard rifle floorplate and was not intended to be detachable. The same extension magazine pattern was also used with the rare experimental Cameron-Yaggi M1903 “Trench Periscope Rifle.” Also, it is not widely known if fairly sizeable numbers of these magazines were fabricated for use with standard M1903 service rifles for trench warfare. However few, if

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

any, were actually issued before the Armistice. Most of these magazines were apparently destroyed after the war as surviving examples are relatively scarce today.

Even though General Pershing requested 825 Air Service Rifles, Ordnance Department documents reveal that 908 of the weapons were manufactured and shipped from Springfield Armory to France on June 25, 1918. The exact date the weapons arrived in France, or the reason(s) for the additional 83 rifles, is not known. On November 5, 1918, only a few days before the Armistice, a memo by Head of Aircraft Armament Service Headquarters, Lt. Col. H. J. Maloney, stated that 680 Air Service Rifles were in storage in Is-sur-Tille, France. The distribution of the 228 rifles (the difference between the 908 shipped to France in June and the 680 in storage) has not been accounted for.

Interestingly, Lt. Col. Maloney’s communiqué stated that these rifles “were definitely not needed as armament for observers in aircraft” lends even more credence to the assumption that the rifles were intended as personal armament for downed pilots and not for defensive armament in airplanes. Other Ordnance documents of the period confirm that 25 Air Service ’03s were tested by the infantry to evaluate the suitability of the 25-round extension magazine for ground combat use. The results of such testing have not been discovered.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Springfield Armory report for the fiscal year of 1920 stated that the 910 rifles “stripped for Air Service” had been manufactured, which indicated that two additional rifles beyond the 908 sent to France in June 1918 had been manufactured. It would seem apparent that this figure (910) represents the total production of Air Service ’03 rifles.

It is interesting to note that the same pattern stock, handguard and barrel band used with the Air Service ’03 rifle were also used to assemble the handful of experimental M1917 rifles altered for sniping use and tested with a prototype Winchester telescope late in WWI. The telescope was eventually adopted as the “Model of 1918” and was intended to be teamed with a modified M1917 rifle. However, the sniping rig was not standardized and only a very small number were manufactured for experimental purposes.

Out Of Service

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After the end of World War I, the Air Service ’03 rifles were returned to the United States and put into storage until their ultimate disposition could be determined. It has been suggested that some of the Air Service rifles were perhaps used in Navy dirigibles in the 1920s and 1930s, but no evidence to confirm this has been forthcoming.

In the mid-1920s, the decision was made to convert some of the Air Service rifles to standard service rifle configuration and to destroy the balance of rifles not converted. The reason(s) for not converting all of the Air Service Rifles is not known. An Ordnance Department memo dated June 19, 1925, stated that 139 Air Service Rifles were converted to service rifle configuration at Raritan Arsenal in New Jersey.

The memo stated, in part: “Information is furnished that the modification of the caliber .30 Rifles, altered for aircraft use…required re-stocking and substituting movable stud and…sight leaf…One hundred and thirty-nine (139) of these Rifles have been modified as stated above and are now available for issue as U.S. Rifles, caliber .30, M-1903 at a cost of $168.38.” Although no further documentation on the subject has been discovered, the remaining Air Service rifles were undoubtedly either destroyed or converted at other ordnance facilities.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Surviving examples of genuine Air Service M1903 rifles are quite rare since they were not made in large numbers and virtually all were subsequently converted to service rifle configuration or destroyed. Determining today’s market value for an original specimen would be difficult since not enough have changed hands to establish any comparable values. However, these rifles are substantially rarer than either “rod bayonet” M1903 rifles or Pedersen Devices.

There have been some standard M1903 rifles sporterized and fitted with one of the surplus 25-round extension magazines that some owners believe to be genuine Air Service rifles. However, these are generally easily spotted by the incorrect serial number range and the identifying features specific to the genuine article. Fabricating a convincing bogus example would be more difficult than it might appear.

- RELATED STORY: 8 Rimfire Replicas of History’s Greatest Battle Weapons

A cut-down standard M1903 service rifle stock would be readily apparent because of the inletting inside the stock, and the recess for the rear sling swivel would be obvious. Likewise, the configuration of the Air Service handguard would preclude a standard M1903 handguard from simply being shortened. It is conceivable that a new stock and handguard of the proper configuration could be fabricated and artificially aged to mimic the real thing but such forgery, thus far, has not been reported. Any purported genuine Air Service rifle offered for sale should be examined very closely and, if possible, someone with expertise on the subject should be consulted.

While never used for its intended purpose, the Air Service rifle is yet another example of how the venerable Model 1903 Springfield rifle was modified to meet a requirement that was never conceived of when the weapon was adopted back in 1903.