Seminal events in law enforcement—the 1963 “Onion Field” incident; the 1970 Newhall, California, shootout that left four young highway patrolmen dead; the 1986 Miami shootout between members of the FBI and bank robbers Platt and Matix; and the 1997 North Hollywood firefight between heavily armed and armored bank robbers Phillips and Matasareanu and members of the LAPD, where “willpower defeated firepower”—these events and countless more have shaped and molded American police training and equipment.

Each incident pitted patrol officers and/or plainclothes investigators against determined and hyper-violent criminal suspects, and each one resulted in firearms training changes and examinations into ballistics and handgun performance on the street.

Whether it was the greater capacity and reload speed of the semi-auto handgun as proven at Newhall, the terminal ballistic performance of LE ammunition and the effectiveness of a .223 carbine brought to the fore in Miami and again in LA, there were many “lessons learned.” One of those, the “Onion Field insurance,” or carrying a backup gun, has been around since lawmen first pinned on a tin star, and it has survived the test of time.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

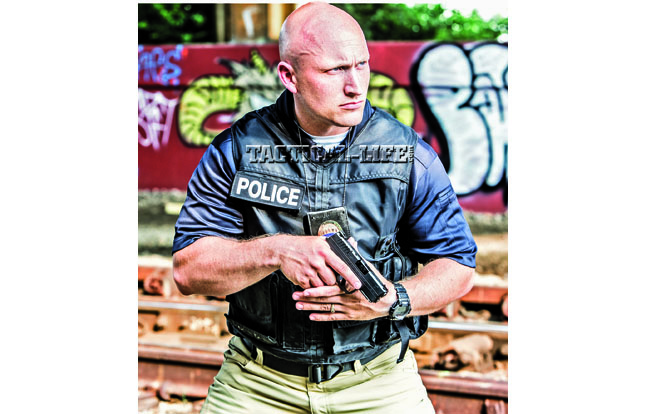

Ready for Anything

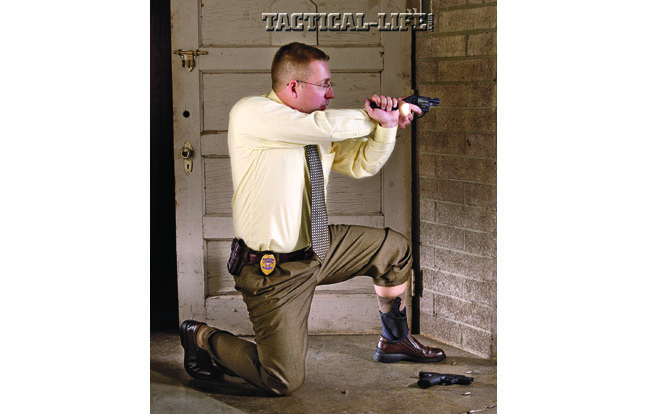

Listen to the words of FBI Agent Ron Risner as recorded in the FBI training video made after the Miami shootout. When asked, “How much ammunition would you fellows recommend that an agent carry?” Risner responded, “In this particular situation, as much as you can carry. I know a lot of agents use revolvers with no pouch or spare ammo. In a confrontation, they’ve got five or six [shots] and that’s all.” Risner was one of three agents in the Miami shootout to use a 9mm semi-auto, and he also drew a backup 2-inch-barreled .38 special revolver from an ankle holster and fired it before reloading his main pistol. Agent Jerry Dove expended at least 20 rounds from his 9mm Smith & Wesson semi-auto before he was shot and killed by suspect Platt with his .223 rifle.

One agent wounded in the shootout was effectively unarmed during the firefight when his revolver, which he had placed under his thigh while in his unmarked cruiser, was lost when his car collided with the suspect’s vehicle prior to the shooting. The revolver was knocked out from under his leg, and he was effectively unarmed and subsequently shot and wounded.

Yes, even large-frame pistols or those that carry 17 rounds or more can run dry, experience a parts breakage, or be lost or taken away in a dynamic, ultraviolent encounter. Through the ages, experience calls for a backup gun, and we need to listen to the hard-won experience of those veteran police gunfighters who survived.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Before You Carry

First and foremost, a backup gun must be reliable. If the backup gun won’t reliably go bang, then don’t carry it. The truth is that you’ll be drawing this when things are really bad, and it needs to work!

The next consideration is caliber. When I was a young deputy, many cops carried .25 ACP semi-autos as backups. Listen, I’ve shot a couple of feral animals with .25s and dropped them with one shot. I carried a Beretta Model 20 as a backup gun loaded with Winchester 45-grain Expanding Point ammo for a short while. This arrangement is certainly not my first choice for a backup when things go south.

My opinion is that the .38 Special is the lowest-velocity round I want to carry. That said, metallurgy and revolver design/manufacture have improved to the point where small, lightweight .357 revolvers can be carried as backups. No, I would not want to shoot a lot of magnum loads downrange with a 2-inch-barreled, five-shot .357, but you can always train with .38s, even +P rounds and some .357s, and carry the full-charge magnum loads on duty.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Over the years, I’ve carried my old S&W Chief’s Special as backup in a variety of different ways. I’ve carried it in a Renegade Holsters ankle rig, a pocket holster from Uncle Mike’s and stuffed in my waistband using a Barami Hip-Grip in plainclothes. Pocket carry is the most secure and most comfortable. We used to wear Tuffy waist-length coats or parkas, which allowed us to carry a small revolver in our outside or inside coat pocket. Heavy coats have mostly gone away except in the coldest climes, and the newer-fabric jackets and windbreakers would sag to one side if a pocket were used. What is nice is that cargo pockets on duty trousers now offer another carry option. Regardless of which pocket you choose—front pants, rear or BDU—a holster is mandatory to properly position the handgun for the drawstroke and to protect the trigger from an unintentional press.

With today’s small 9mm and .45 semi-autos, why carry a .380? With semi-autos, I’ve always been partial to holsters that affixed to the straps of my concealed body armor. For years, I carried a S&W Model 3913 in a Horan Hide-Out

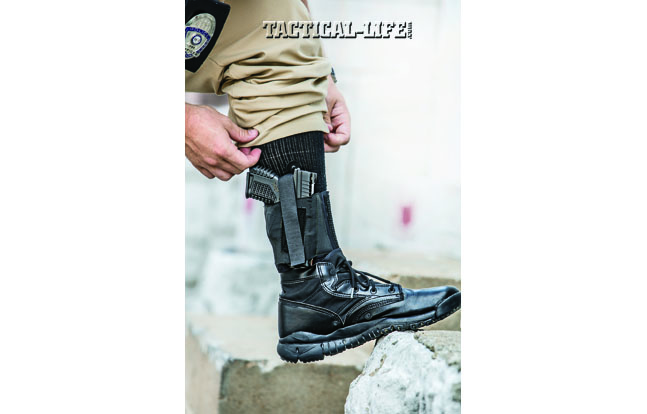

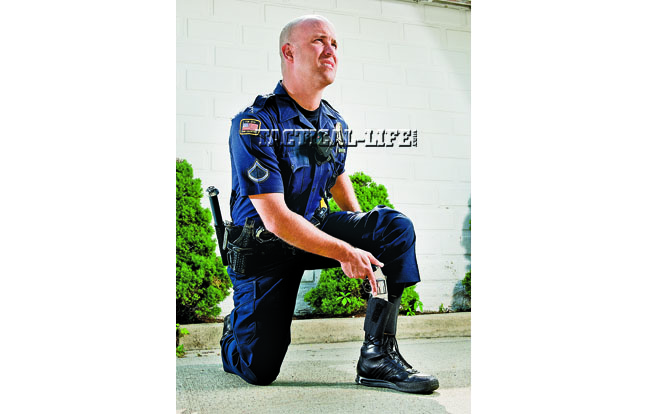

holster. Made of leather, the gun/holster combo was carried vertically (muzzle down) under my weak-side arm, similar to a shoulder holster. When I began carrying a Glock 19 as a duty sidearm, I replaced the 3913 with a Glock 26. The current concealed armor holster I use is an Aker Model 150 Hideout Holster. With many officers now opting to wear external vest carriers, inside-the-shirt carry may no longer be an option for them. However, if the external armor vest is equipped with MOLLE straps, a nondescript holster pouch on the vest can be substituted. As noted earlier, ankle holsters are a good option. Their unorthodox location can actually be a benefit in some situations, and with the plethora of high-quality, ultra-compact autos and revolvers around today, they can be a viable option.

Deep-Cover Tactics

Revolvers can be fired through coat pockets and still function. With no external safety and a heavy double-action trigger pull to fire, a small, five-shot wheelgun can still be effective for backup purposes even in this day and age of 18-shot duty pistols.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Another thing that revolvers have going for them is that they are more forgiving of muzzle-contact shots than semi-autos are. Imagine a close-range, grappling, “bad breath distance” encounter with a suspect. Your duty pistol is out of the picture; your gun hand is desperately holding it in the holster, but you’re able to access the backup gun in your weak-hand pants pocket. You shove that small-frame 9mm into the gut of your assailant and pull the trigger. But A) the gun is out of battery and won’t fire, or B) the pistol fires once, then won’t function because blood and goo blowback onto the pistol has created a malfunction. Substitute a small-frame revolver, and the gun goes bang. (Caveat here: The external hammer must not be blocked if the wheelgun is so equipped. This is a good reason to have an internal- or bobbed-hammer model.) Think this can’t or won’t happen to you and your semi-auto? I know one officer who had this happen to him when the suspect jumped on him after he tripped backward.

These smaller-frame pistols and revolvers have a decreased ballistic impact on a suspect because of reduced velocities, but that said, hitting the target—always a priority—is vital when you’re in an encounter and you’ve been forced to transition to a backup gun. As a firearm’s instructor, I recommend that your default position be a two-handed, eye-level shooting platform. Anything less than that is a compromise based on time, distance and the dynamics of the encounter. If you can’t bring the pistol up to your eye level with two hands, try to do it with one and get some index of “metal on meat.” If you’re in a fight for your life—“in the hole,” as extreme close-quarter shootings have been referred to—then retention-position shooting or shove-it-in-their-gut-and-fire techniques may be called for. This may not be the type of shooting you do on the range during firearms training; it’s the kind you do when you’re rolling around in the gutter, attempting to stop a homicidal whack-job from trying to kill you. In your ongoing training regime, remember to work with your backup gun so that you have a “motor program” or skill set you can revert to without any thought or interruption.

Life-Savers

Several years ago, a young narcotics K9 handler confronted a suspected dealer in a suspicious person stop. The dealer resisted the frisk, and the fight was on. The officer was taken down to the ground and after a serious fight, the dealer was able to disarm the smaller officer. The officer had a backup gun in a spare handcuff case on his belt; he was able to draw a small-frame semi-auto and fire at the suspect. The suspect ran a short distance before succumbing to his wounds. This young cop fulfilled his #1 mission—he went home at the end of his shift, and his backup made it happen.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

From a brace of revolvers carried by Old West lawman, through the infamous Miami Shootout, to today’s mean streets—backup guns have proven themselves and their worth, saving officers’ lives in the process. Get, train with and carry a backup gun. Your life is worth it!