The Battle of the Bulge was the largest battle ever fought by the United States Army. Lasting a full month, the battle encompassed some 4,250 square miles as German units attacked on an 85-mile front, with their deepest-penetrating unit driving 50 miles into the American lines. The battle is named for the huge bulge in the front created by the German assault.

The Battle of the Bulge

By the time it was over, some 30 American divisions took part, with seven or eight engaged at any given time. The Bulge was an “all hands on deck” situation, with clerks, truck drivers, and cooks grabbing rifles and slugging it out. The brutally cold weather, frozen landscape, and low overcast meant that soldiers fought the elements as much as they fought the enemy.

In the end, American tenacity won the day, but how did the Germans manage such an attack that late in the war? Enter self-proclaimed military genius Adolf Hitler.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Surprise, Surprise

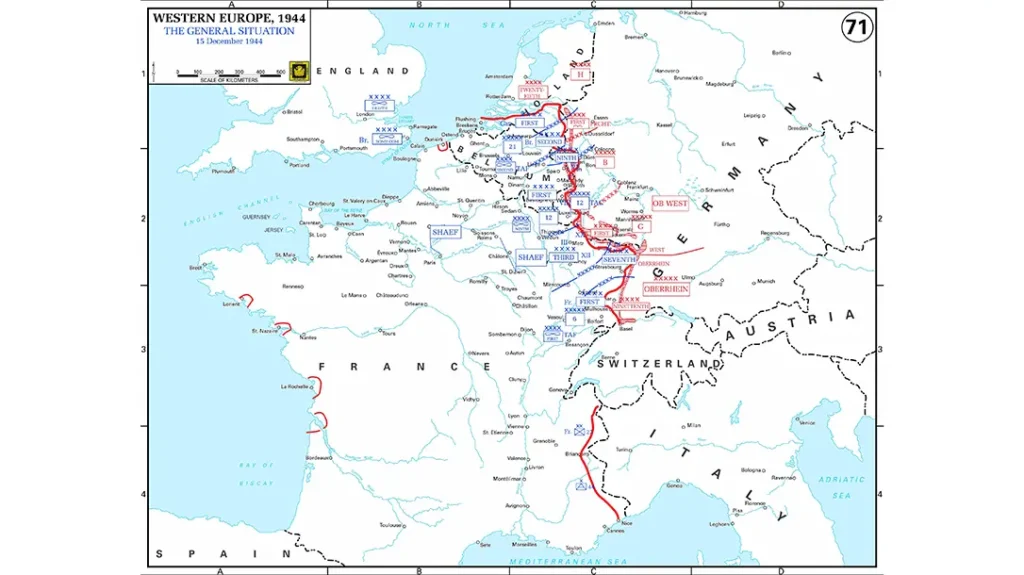

By late 1944, the Allies had booted the Germans out of France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and part of Holland. But German resistance had stiffened in the Hurtgen Forest and the Dutch city of Arnhem. The Allies were still looking for a way across the Rhine River into Germany itself, but didn’t plan to make that push until early 1945.

The U.S. Army was resting its veteran units while slowly introducing green formations to the front line. Many soldiers had leave in France or Luxembourg, and even the line units were down some manpower. All signs indicated that the Germans were strengthening their defenses against the upcoming Allied offensive, but nothing more.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But Hitler had other ideas. In the strictest secrecy, he and a few trusted officers planned an operation of his own concoction: a surprise attack through the heavily wooded Ardennes region. The offensive aimed to seize the Belgian deepwater port of Antwerp, thus denying it to the Allies, and hopefully cutting off the better part of two Allied Army Groups.

Target Acquired

Hitler correctly identified Antwerp as a valuable target. The city was the first major port the Allies had captured since the Normandy landings. In fact, tons of supplies were still coming across those beaches for lack of adequate port facilities. Antwerp would allow them to supply a major thrust against Germany in 1945.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Hitler also identified the Ardennes as a perfect place to spring his surprise. The sector had been quiet, occupied by resting Allied divisions and a few new units being prepped for combat. Finally, the plan had a precedent. German armored units had attacked through the Ardennes in 1940, surprising the French, who thought it was impassable for armor. The German attack unhinged the entire Allied defense, leading to the evacuation at Dunkirk. Hitler believed he could repeat that success and capture Antwerp.

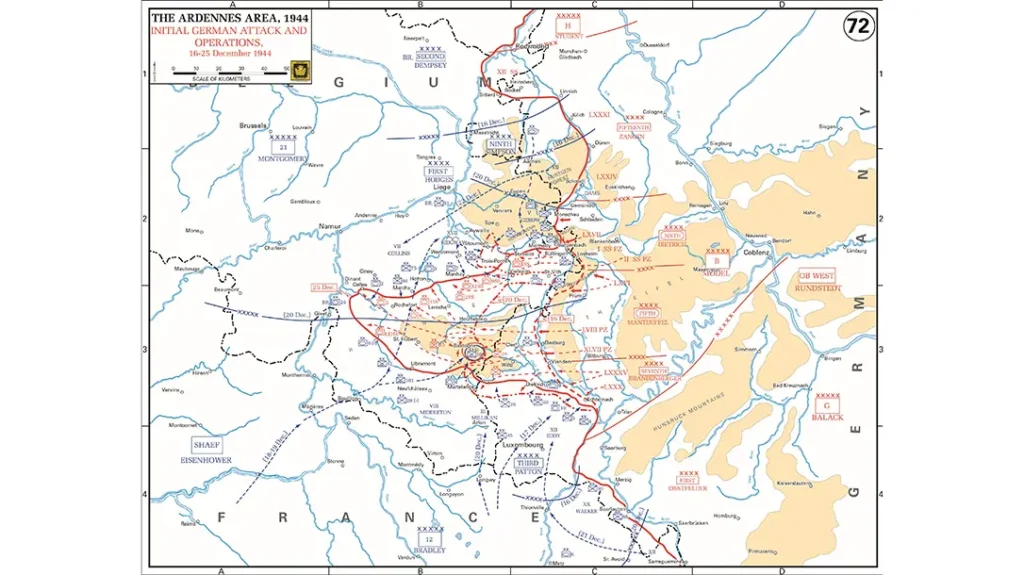

The Germans amassed a veteran assault force under the guise of building up their Westwall defenses. The soldiers themselves believed that they were doing just that. Even then, the troops and equipment only moved at night. The unit commanders only learned their true mission a few days beforehand, and the assault units only moved to their jump-off points a few hours before the attack began in the predawn hours of December 16. They achieved complete surprise.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But 1944 Wasn’t 1940

The German armored columns moved out quickly, following a sudden artillery barrage. They leveraged the low cloud cover by bouncing powerful searchlights off the overcast, creating what they called “artificial daylight.” The frozen roads provided good support for the heavy Tiger and Panther tanks. The clouds also kept the Allied fighter-bombers grounded.

The Americans were surprised, but unlike the French in 1940, they weren’t paralyzed. Better communications, a better command structure, and a familiarity with mobile operations meant the U.S. soldiers knew how to counter such an attack, where the static French doctrine of 1940 had not prepared their troops, or their commanders, to fight a highly mobile opponent.

The Americans instantly fought back, some in place, while some withdrew, blocking the narrow forest roads as they went. Hitler was a talented amateur tactician, but he was not a professional logistician or operational planner. His timetables were too tight and relied on everything going according to plan. Stiff American resistance immediately imperiled those timetables. Unable to deploy in the wooded country, German columns stacked up on the narrow roads.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

German Struggles

The Germans also lacked fuel. Part of the plan required them to capture American fuel dumps to continue their advance. The hours-long traffic jams caused by American resistance meant their tanks and trucks burned thousands of gallons of irreplaceable fuel while idling. Some German units were as much as twelve hours behind schedule by the first day’s end. An 18-man American reconnaissance platoon held up an entire regiment of the German 3rd Parachute Division for most of the day before being overrun when they ran out of ammunition.

But it was expensive. U.S. forces took heavy casualties while buying time for General Dwight D. Eisenhower to marshal reinforcements. The green 106th Infantry Division, sent to Europe before it was ready, fell apart while trying to break out after being surrounded in the first hours. Even so, they bought time as the Germans were forced to deal with them. But the rout was so bad that the Army quietly decided not to reconstitute the 106th, sending its survivors to other units.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The American sacrifices and dogged resistance quickly put the Germans behind schedule across the entire front. But things were about to get worse.

“Nuts!”

The siege of Bastogne is probably the most famous part of the Battle of the Bulge, with good reason. Hitler had identified Bastogne’s importance to his advance and detailed the crack Panzer Lehr Division to seize it. Bastogne was a major road junction, controlling six major routes in and out. The recuperating 101st Airborne Division was rushed to the front, without winter supplies and low on ammunition, to hold Bastogne.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The division commander, General Maxwell Taylor, had been called to Washington for consultations because no one expected any serious action until after the New Year. Oops. Taylor’s Deputy Commander, Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, was authorized to retreat as Bastogne was in danger of being surrounded. McAuliffe declined, and just made it into the 101st perimeter as the German trap closed on December 20. But besides the 101st, McAuliffe had extra firepower from half of the 10th Armored Division and the veteran 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

Bastogne was surrounded, but the German armor couldn’t move through the trees, They needed the town and its road junction. German artillery pounded the town, and McAuliffe estimated he could hold for two days with what he had. At the end of those two days, on December 22, McAuliffe received a German surrender demand.

McAuliffe Reply:

To the German Commander:

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Nuts!

The American Commander

Colonel Joseph H. “Bud” Harper, who commanded a battalion of the 327th Glider Regiment, delivered the reply. When handing it to the German officer who brought the surrender demand, Harper growled “If you don’t know what ‘Nuts’ means, in plain English it is the same as ‘Go to Hell.’ And I’ll tell you something else – if you continue to attack, we will kill every G–damn German that tries to break into this city!”

The paratroopers hung on and were relieved by the 4th Armored Division on December 26, four days longer than McAuliffe believed he could hold. The 101st troopers, to this day, have never admitted that they needed to be relieved.

The End

Bastogne’s road junction was a linchpin of the German plan. Without it, the attack was dead in the water. But American troops had blocked the German columns almost everywhere, forcing them to burn more fuel looking for alternate routes through the forest. When those routes were also blocked, the attack lost all momentum and was set up for a counterattack. Looking the map, one can see that the Bulge tapers almost to a point.

The point represents the farthest German advance, which was accomplished by Lt. Colonel Joachim Peiper’s First SS Panzer Regiment. Peiper’s tanks eventually ran out of fuel, whereupon he and his men abandoned them and walked back through the woods to German lines. He was a full four miles short of the Meuse River, which he was scheduled to reach in two days.

The Germans had overextended themselves. Now they were out of gas and out of options. Strong Allied counterattacks, aided by clear but still cold weather, drove them back to their starting points by mid-January. Hitler’s gamble failed without even threatening Antwerp.

A Foolish Exercise

Despite catching the Allies by surprise, the 1944 Ardennes Offensive never really had a chance. The plan was overly optimistic, and Germany lacked the logistical capability to sustain it, even if it had reached Antwerp. The lack of fuel reserves is indicative of the plan’s weakness in the face of two powerful Allied Army Groups operating literally on their own bases of supply, even if they were caught off guard.

In the end, Hitler threw away numerous veteran units, thousands of men, and tons of supplies in an operation that was doomed to failure. Those assets would have been better employed defending Germany from the upcoming Allied offensive. All they accomplished at the Bulge was to speed up Germany’s inevitable defeat.

Learn more at the Bastogne War Museum.