Writing about secret developmental aircraft is a dicey proposition, since little or no information about these platforms is often available. In researching the aircraft, dubbed the “Bird of Prey” by McDonnell Douglas Phantom Works engineers because of it’s distinctive gull-shaped wings, neither the company nor Air Force spokesmen were willing to share much information on the unique aircraft.

“Although the YF-118G program was declassified, many of the technologies embodied in its design remain under wraps because they continue to be applied in more current black projects…”

What little we know about the Bird of Prey comes from official Boeing and Air Force summaries. The project started in 1992, and developmental costs, provided entirely by the company, totaled about $67 million, although the Air Force agreed to manage the program and provided flight test facilities and services at the Nevada Test and Training Range at Groom Lake. McDonnell Douglas merged with Boeing in 1997, which continued the program until 1999. The Air Force formally declassified the project in 2002. Today, the Bird of Prey is on display in the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, a testament to the design excellence that made the single technology demonstrator a success. Many such secret prototypes, including both Lockheed Have Blue prototypes, predecessors of the F-117 Nighthawk stealth fighter, crashed during their test flights and were buried in undisclosed locations on Nellis Air Force Base, near Groom Lake.

Check out this article about Air Force Combat Arms: The Best Job No One Knows About!

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Although the YF-118G program was declassified, many of the technologies embodied in its design remain under wraps because they continue to be applied in more current black projects, even though follow-on programs using some of the same systems, such as the X-32, Boeing’s unfortunate losing entrant in the Joint Strike Fighter competition in 2001, and the X-45 unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV) that ended in 2008, never began production.

Streamlined Design

The aircraft’s first purpose was to prove out stealth technology, the design and manufacturing processes and techniques that greatly reduce the radar, infrared, acoustic and visual signatures of aircraft, making them far more difficult to detect by a wide variety of electronic sensors. In addition, McDonnell Douglas wanted to build a prototype quickly and efficiently to enhance its competitive edge in winning government-funded contracts. Structural sections were large by industry standards, although the Bird of Prey paved the way for production methods widely used today. Other innovative steps, now routinely utilized, included relatively inexpensive disposable tooling used for composite lay-up and three-dimensional, computer-aided design.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Although most of us would consider a $67 million price tag as eye-wateringly extravagant, the reality is that this amount is bargain-basement low. Developmental budgets for new aircraft designs routinely involve hundreds of millions, and the most sophisticated new aircraft can exceed $1 billion.

“Consistent with its low-observable characteristics, the Bird of Prey was assembled using carbon-fiber composite materials…”

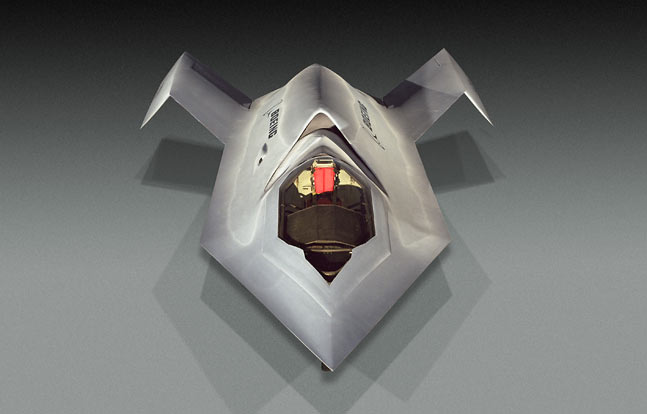

The low budget was, however, a double-edged sword. The Bird of Prey, an astonishingly advanced design, had very rudimentary systems in the cockpit and throughout the fuselage. After all, the primary test issue was observability, not performance or handling qualities. One look at the aircraft’s slender profile makes its purpose clear. Vertical surfaces, especially a vertical stabilizer, are absent, making the aircraft very slender indeed. The fuselage is shaped like the gladius, the short sword widely used by the ancient Roman army, and the wings are extremely short, with a gull-shaped wingspan just under 23 feet—less than half the fuselage length—and folded, with dihedral (upwardly angled) inboard sections and anhedral (downwardly angled) outboard sections. The aircraft’s small size, absence of vertical surfaces and streamlining to eliminate flat reflective surfaces and shadows combined with a narrow engine intake placed just behind the cockpit on top of the fuselage and few if any other visible openings in the fuselage, including “gapless” control surfaces and a blended fuselage and wing. In fact, the prototype looks remarkably like a folded paper airplane.

Consistent with its low-observable characteristics, the Bird of Prey was assembled using carbon-fiber composite materials. Such composites are very light but surprisingly strong, contributing to the relatively light weight of the aircraft—just 7,400 pounds. Carbon-fiber composite panel construction provides great strength, since, as the name suggests, the fuselage and wing panels are made from thousands of interwoven fibers, bonded with resin material in high-heat and high-pressure ovens known as autoclaves. Damage to such composite is almost always contained to the immediate area of impact, since the short fibers do not propagate structural breakage, unlike metal, which acts like one continuous fiber when struck with significant force. After inspection to ensure the panel skins, about the same thickness as aircraft aluminum, contain no voids, cracks or other imperfections, they are trimmed, fitted and assembled.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In addition to its strength and resilience, carbon fiber provides another distinct advantage. It has a low radar signature because its fibrous structure does not reflect radio waves uniformly. Furthermore, although the aircraft on display at the USAF Museum apparently doesn’t contain any visible evidence, the fuselage may also have been wrapped in anechoic material, a soft cover that also absorbs radar, or may have been covered with non-reflective paint during flight tests, or even coatings that could change color or luminosity, much like a chameleon, to enable the aircraft to fly during the day without being observed. Neither Boeing nor the Air Force will confirm this possibility, however.

Controls & Power

As noted, this extremely sophisticated structure and form utilized far less capable flight systems. The flight control system was manual, with no computer controls, to save money. It used mechanical actuators with hydraulic power linked to elevons on the inner wings and rudderons on the outer wings for roll control. Cockpit instrumentation was “commercial off the shelf” (COTS)—the same instruments found in many private general aviation aircraft. Other components from earlier military aircraft were also installed. The tricycle landing gear was adapted from those found on the popular Beechcraft King Air and Queen Air twin-engine airplanes.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

“Only three pilots flew the Bird of Prey, and all of them had their doubts about the test aircraft’s handling qualities…”

The Bird of Prey’s propulsion system was also COTS—the Pratt & Whitney JT15D-5C turbofan engine used on the Cessna Citation business jet. The engine gave the prototype an operational speed of about 300 mph (260 knots) and a ceiling of 20,000 feet. These relatively modest capabilities were sufficient for the primary test purpose: determining low-observable signatures with a variety of sensors.

The design and rudimentary onboard systems raised serious questions about the aircraft’s safety in flight, despite assurances from the Bird of Prey’s design engineers. After static and high-speed taxi tests indicated possible issues with thrust and roll—all resolved with further evaluations—it was clear that actually flying the prototype would be a dicey proposition. Only three pilots flew the Bird of Prey, and all of them had their doubts about the test aircraft’s handling qualities. One test pilot reportedly resigned during high-speed taxi tests that indicated potential handling problems. This decision enabled Rudy Haug, originally assigned as the backup pilot, to complete the brief first flight with landing gear extended on September 11, 1996. Haug landed safely but reported handling problems. Adjustments completed after each early flight improved the aircraft’s stability, and Haug retracted the landing gear for the first time on the sixth flight. Haug completed eight flights and was followed by Air Force Lt. Col. Doug Benjamin, who commanded the Bird of Prey Combined Test Force for the Air Force. Benjamin flew 21 flights in the aircraft, including its last in 1999, expanding its operational envelope and observability testing. Boeing test pilot Joe Felock logged nine flights, raising the total to 38 sorties and averaging about a flight per month before the aircraft’s retirement in the spring of 1999.

Given the Bird of Prey’s handling issues, the risk undertaken by the three pilots during these flights was unusually high and resulted in the Society of Experimental Test Pilots’ Iven C. Kincheloe Award for outstanding professional accomplishment.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Under The Radar

Boeing and the Air Force revealed the Bird of Prey on October 18, 2002, and the plane soon found a permanent home on display at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. Only one Bird of Prey exists, and it flew fewer than 40 missions in less than three years, but the little prototype’s influence has been far-ranging since it demonstrated an entirely new configuration for advanced military aircraft, manned and unmanned, that permits them to fly combat missions and return safely home while avoiding detection by very sophisticated sensor systems that would find and track conventional airplanes, making them vulnerable to countermeasures that could compromise their capabilities or lead to their destruction. A worthy legacy, indeed!

Specifications: Boeing YF-118G Bird of Prey

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

- Length: 47 feet

- Height: 9.3 feet

- Wingspan: 23 feet

- Crew: 1

- Powerplant: 1 Pratt & Whitney JT15D-5C

- Thrust: 3,200 pounds

- Max Takeoff Weight: 7,400 pounds

- Rate of Climb: 3,000 fpm

- Ceiling: 20,000 feet

Take a look at this article about America’s Cold War Supersonic Marvel – The XB-70 Valkyrie!