For 101 years, John M. Browning’s 1911 .45 ACP has been an issued sidearm—and a preferred one, even today—for American GIs. The 1911 .45 ACP has been known by many names, and virtually every one is synonymous with “stalwart.”

This inherently flawless (a term preferred over “classic”) pistol has been used by some three dozen other countries and copied by more makers in various calibers, tweaks and iterations that you can count. A list of quality makers currently producing the basic 1911 design would fill a page in a phone book. During the transition of the great police wheelgun, the 1911 .45 ACP competed favorably with a whole new generation of “Wondernines,” which came to the fore after WWII. Today, it competes with a new generation of double-action, high-capacity autoloaders in the same git-’er-done .45 ACP caliber. We find this particularly interesting because, back in “the day,” the M1911 Colt had two features no other gun could compete with: best-friend reliability and the incomparable .45 ACP round. A hundred years later, other handguns are being made in .45 ACP, and Colt and a legion of copyists made the M1911 design in all the usual calibers, but the M1911 in .45 ACP continues as a winning, if not unbeatable, combination.

Why .45 ACP

The .45 ACP is a round that is frankly hard to argue with. It has an unsurpassed record as a fight stopper, whether you measure a round’s efficacy by the Marshall-Sannow or Fackler (or even Elmer Keith) method of accounting. It’s just hard to argue, even with the best scientific sophistry, with a cartridge that has a 100-year track record of knocking ’em stiff.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Recent combat experience tends to reinforce the comparative advantage of .45 ACP versus the 9mm round. Without tiptoeing into the interminable debate (of course, we would never want to be shot with a 9mm), we will simply note that, in the recent past and today, those troops whose mission depends on a pistol will often opt for a .45 ACP. Many of these are new iterations of the M1911, and some are new designs, ones in this caliber by other makers. As full disclosure, we should note that, among many of us old GIs who were issued the 1911A1 for everyday carry, familiarity and confidence bred a lot of preference, and this admittedly may come at the cost of some objectivity.

There is a common perception that design and technology advance with time, that every new model must, by some natural law, be better than its predecessor. Sometimes this is true. Sometimes it is not: in the case of the 101-year-old M1911 .45 ACP pistol, books could be written of the newer designs that came along only to disappear because they could not compete with the original. If history is any indication, at least some of the current offerings will also turn up in the parts bin of history, certainly long before John Browning’s Colt .45 will. At the risk of sounding like an old coot filling out a form for a dating service, sometimes older is better.

Nostalgia keeps some interesting things around, long after they are out of production. The Luger P.08 or M1896 Mauser come to mind. However, excellence keeps some designs not only around but also in production—and not only in production but also in new, diverse and ever-increasing production. Of this genre, I can think of no better example than the M1911. This excellence benefits 1911 aficionados because makers and custom builders compete to offer quality manufacturing and because aftermarket businesses supply an array of innovative tweaks, modifications, accessories, custom parts, sights, carry rigs, bells, whistles and adornments.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Wartime Pistol

During peacetime, on a predictable schedule, some never-been-shot-at pencil pusher will compile some numbers proving that American warfighters don’t need handguns: they note that the soldiers’ other weapons account for many more enemy casualties. But do we ask (while ignoring the fact that handguns are primarily defensive weapons) if we should get rid of rifles because more enemy are killed by artillery, or if we should only train soldiers to sharpen punji sticks and make homebrewed grenades because more casualties in Vietnam came from booby traps than from small arms? Of course not. Each genre has its role, and the American fighting man has always been well served, and has served well, when he had a Colt .45 on his hip, serving as a self-defense weapon.

BACK TO BASICS

American military forces began shopping for a new handgun in the late 1800s because the .38 Colt revolver proved ineffective. As a new genre of autoloading handguns appeared, the U.S. tested models by Mauser, Steyr-Mannlicher, DWM (Luger) and Browning (Colt M1900). The common denominator among these guns was their ineffective cartridges. Experience in the Philippine Insurrection and extensive cartridge tests by Colonel John T. Thompson (later inventor of the Thompson submachine gun) were clear: yes, we wanted an autoloader, but it had to be in no less than .45 caliber.

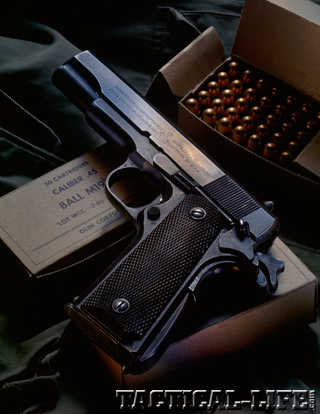

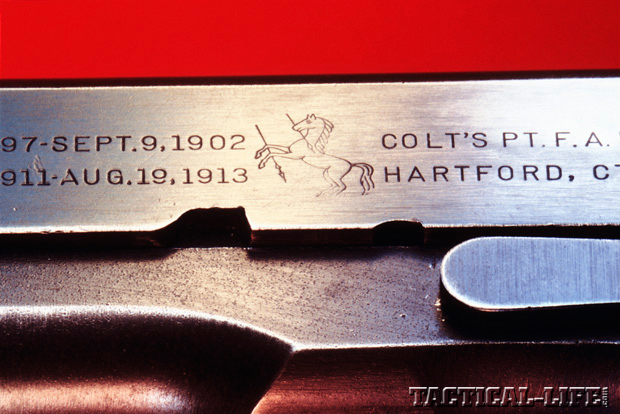

Design submissions in .45 ACP by Colt, Bergmann, DWM, Savage, Knoble, Webley and White-Merril were quickly short-listed to the Colt, DWM and Savage. The DWM, a Luger scaled up to .45 ACP, fell first. The Savage went next in a final grueling test: it had 37 stoppages while the Colt fired 6,000 rounds without a hitch (it was periodically dunked in a water tank to cool it off). Re-engineered from Browning’s original 1900 short-recoil locked breech, in 1911 the .45 Colt design was officially adopted in its final form: it weighed 39 ounces empty; it was 5.25 inches high and 8.25 inches long; its magazine held 7 rounds; and its barrel had a 1-in-16-inch twist rate. The design features a strong breech where, on firing, the barrel, frame and slide are solidly locked as a unit. The recoil pushes the slide rearward, which unlocks the breech then continues on to extract and eject the casing. It then returns to battery, picking up and chambering a fresh round as it goes forward to once again be solidly locked.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

WWI was a brutal faceoff, employing new weapons and outmoded tactics. Ground combat involved small-unit raids and CQB, between suicidal assaults and into entrenched enemy lines. John Browning’s new .45 pistol proved to be up to the job and quickly become a favorite among American troops and not just as a comforting companion. During one legendary engagement, Sergeant Alvin York (Medal of Honor recipient) used a M1911 to stop an attack by six German soldiers, killing six with six shots from his .45. Lieutenant Frank Luke (Medal of Honor recipient) single-handedly fought to the death with his .45 pistol, after his SPAD fighter plane was forced down. Other new weapons that emerged from WWI included tanks, fighter planes, rapid-fire artillery, machine guns and submarines. All of these types of weapons are still represented in modern arsenals, but after 100 years only the M1911 Colt .45 pistol has soldiered on in the same uniform—because it’s that good.

After an intense conflict, armies try to catch their breath and evaluate the weapons and tactics that served them well. The judgment of the M1911 .45 in summary was, “This one’s a keeper, how can we make it better?” The short answer was, “There’s nothing wrong with it, but there is something we can do.”

The M1911A1

By 1924, minor external changes were incorporated to make the .45 pistol more user-friendly without changing the intuitive design. New parts were interchangeable with old. The most obvious change was the one that is most often changed back by aficionados (or excluded from new custom models): the new arched mainspring housing at the bottom rear of the grip. Whether the slightly thicker and arched mainspring housing fits a typical shooter’s hand better than the original flat one, has more to do with individual orthopedics than with overall ergonomics. A significant percentage of avid users think Army Ordnance guessed wrong on this point.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Other minor changes have been better accepted. The crescent relief cuts in the frame just behind the trigger opening give shooters with smaller hands better access for proper trigger press—the cuts do not cause problems for large hands. The shortened trigger has the same goal, although many aftermarket target-type triggers are back to original length. The spur of the grip safety has been lengthened further rearward, to help keep the shooter’s hand safe from hammer bite—on many new custom M1911s, this is extended even further. The hammer spur has also been slightly shortened. The front sight and the rear notch have been widened, a change that’s been made more dramatic on many new custom M1911s or as a retrofit. Finally, the intricate checkering pattern of the wooden grips gave way to synthetic. Custom grips of every conceivable material, texture and configuration are one of the most popular user upgrades.

Most, but not all, M1911s in inventory were converted to the new standard. During WWII, Army Ordnance conducted the usual wonder-what-if experiments with selective fire and shoulder stocks, but no such modifications were considered practical. Aside from slightly downsized models for top brass, no further modifications were made until the M1911 was replaced as the standard handgun by a 9mm pistol in the 1980s. There have been recent minor changes to the M1911A1, developed by or for spec-ops units.

The 1911 went on to be produced on U.S. military contracts in some 2,700,000 units by Colt, Army Ordnance (Springfield), Remington-Rand, Ithaca, Singer and Union Switch & Signal. The rest, as they say, is history—one that’s still being written. Not only is the M1911 still in production, the Browning short-recoil system is the basis for most of the autoloading locked-breech pistols made since that time, by whomever or whenever. It is a true watershed design.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Check out this article about the Air Service M1903 Rifle!