This article on the U.S. military’s Camel Corps is from the Summer 2020 issue of Guns of the Old West magazine. Grab digital or physical copies at OutdoorGroupStore.com.

Called “the ship of the desert” for its ability to cross arid lands like no other animal, some also call the camel “a horse designed by committee,” highlighting its misshapen appearance. But camels actually prove highly efficient and well suited to their desert habitats.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The U.S. Army’s Camel Corps

These animals can run as fast as 40 miles per hour in short bursts, or sustain an average speed of 25 mph over great distances. Their feet provide excellent traction on various types of soil. And as we all know, camels can withstand long periods of time without any external source of water. The dromedary camel, the most common of the three camel species today, can drink as seldom as once every 10 days even in extreme heat, and can safely lose up to 30 percent of its body mass from dehydration.

Desert Mobility

As the American frontier opened in the early 19th century, it remained a rugged and untamed land marked by inhospitable terrain and heat. The Southwest resembled the Middle East with vast deserts, mountain peaks and seemingly impassable rivers. So it isn’t that strange that some American military planners had their own designs on the so-called “horse designed by committee.” The dromedary camel of the Middle East seemed ideally suited for use in the wild American Southwest.

In 1836, U.S. Army Lieutenant George H. Crosman first suggested to the War Department that camels might be just the animals for these harsh conditions. He served at various posts on the frontier and took part in the Black Hawk War of 1832 before transferring from the infantry to the Quartermaster Department.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Crosman submitted an extensive study on the subject of camels to his superiors, and his report noted: “For strength in carrying burdens, for patient endurance of labor, and privation of food, water & rest, and in some respects speed also, the camel and dromedary (as the Arabian camel is called) are unrivaled among animals. The ordinary loads for camels are from seven to nine hundred pounds each, and with these they can travel from thirty to forty miles a day, for many days in succession. They will go without water, and with but little food, for six or eight days, or it is said even longer….”

Crosman’s Influence

However, the War Department largely ignored the Crosman report. It showed no interest in importing Arabian camels. Nothing may have come of it, but Crosman rose through the ranks, and as a major he and fellow officer Major Henry C. Wayne took up the cause anew. In 1847, a new report was submitted to the War Department as well as Congress, and this time it caught the eye of then-Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi.

Davis, who would of course go on to become the president of the Confederate States of America, was known to be forward thinking when it came to military innovations. As chairman of the Senate’s Committee on Military Affairs, he sought approval for the project, and then he was appointed secretary of war in 1853. He presented the idea of using military camels in the Southwest to President Franklin Pierce.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The terrain and climate of the far frontier were proving more hostile than expected, and horses and mules were inadequate for the long, dry treks across the arid land. With the support of Davis, Congress finally approved the plan. On March 3, 1855, $30,000 was appropriated to import camels for the U.S. military.

Acquiring Camels

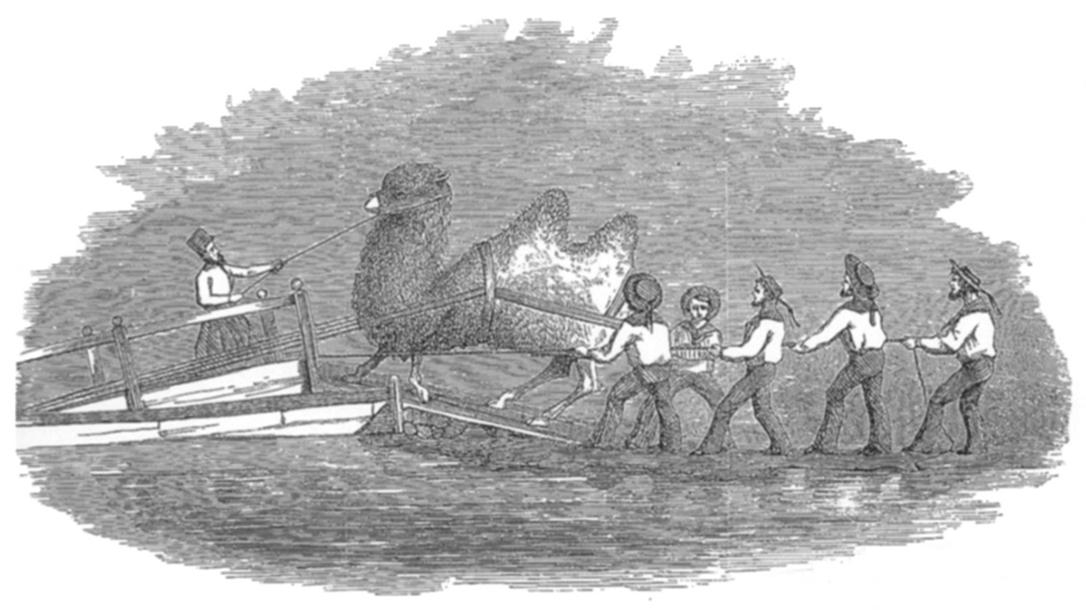

Getting the camels to the U.S. proved less daunting than convincing Congress to undertake the endeavor. In May of 1855, Davis appointed Wayne to the task—and the fittingly named USS Supply, under the command of Lt. David Dixon Porter, was provided to transport the camels from the Middle East to the U.S. The ship was outfitted with special hatches that included stable areas (which may have given rise to the name “camel car”) as well as hoists and slings to transport the animals in reasonable comfort for the long transatlantic crossing.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The USS Supply departed New York City in June of 1855 for the Mediterranean. Interestingly, Wayne and Porter had no set plan about where exactly to obtain the camels. Instead, the expedition made stops at La Goulette in French Tunisia as well as in Malta, Greece, Turkey and Egypt. Camels were purchased from various markets with what can only be described as mixed results. Two of the first three camels acquired in La Goulette were reportedly infected with a form of mange.

Aiding the expedition was the arrival of one Gwinn Harris Heap, Porter’s brother-in-law. He happened to be familiar with various languages, including Greek and Arabic. More importantly, Heap knew the customs of the locations the ship visited during its five-month voyage, and he apparently helped with the bartering and negotiations.

Difficulty in Acquisition

However, the process was still long and arduous. Buying camels, it turned out, proved more difficult than Wayne or perhaps even Davis expected. Yet, all in all, the voyage proved a success, and 33 camels were acquired, including 19 females and 14 males. These included 19 dromedaries with single humps, two Bactrian (double-humped) camels, 19 Arabian camels (a variation of the dromedary), one Tunis camel, one Arabian calf and one booghdee camel (a cross between a male Bactrian and a female dromedary).

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Strict rules were instituted for feeding and caring for the animals, and no one was allowed to experiment with how long the camels could survive without water. Despite these efforts, a male camel and calf perished on the return voyage. But a second calf was born and survived; that brought the total to 34 camels that arrived in Indianola, Texas, on May 14, 1856. A second expedition brought the total number of camels to 70, with an average cost of $250 per animal.

The camels weren’t the only Middle Eastern natives to return to America. Because no Americans knew how to ride or train camels, the task fell to Hadji Ali. He was an Ottoman subject of Syrian and Greek parentage who became the first camel driver ever hired by the U.S. Army. He soon earned the nickname “Hi Jolly” and remained with the camels throughout the program.

In The Southwest

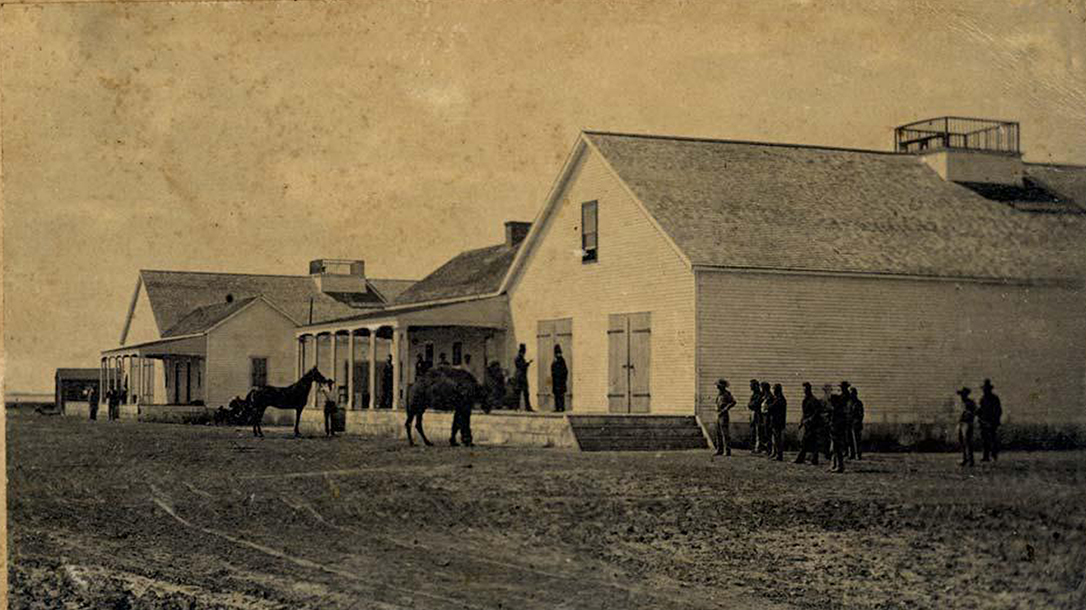

The Army hearded all the animals from the two expeditions to Camp Verde, Texas. Thus began the U.S. military’s experiment with camels. To test the usefulness of camels as pack animals, a team of wagons headed to San Antonio. It took roughly five days for six mules to make the trip while transporting wagons carrying 1,800 pounds of oats. But six camels could cover the same distance with 3,648 pounds of oats in just two days. The results pleased Davis because the tests proved the effectiveness of the camels.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The animals seemed suited to the Southwest. They covered ground faster, required less water than horses or mules, and ate whatever plants they found on the trail. The camels even proved adept at finding watering holes in the arid landscapes.

The Army never realized the camels’ full potential, however. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, camels carried mail between Fort Mojave in the New Mexico Territory to New San Pedro in California. However, the commanders at the post had been cavalrymen. They didn’t like the idea of camels doing the job horses had done so well.

Meanwhile, Camp Verde fell into Confederate hands. Reports said soldiers used the camels to some lesser extent to transport baggage. When Union troops reoccupied Camp Verde, there were more than 100 camels in the camp.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Camels Post-Civil War

While some U.S. government officials gave consideration to using camels after the Civil War, most officials opposed the idea simply because Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, had initially supported it. In addition, the U.S. Army had come to rely on horse and mule trains, and the soldiers simply didn’t have the skills needed to handle the camels.

Just after the end of the Civil War, the camels sent to California sold off at around $52 apiece. Meanwhile, those at Camp Verde sold off at an average of $31 apiece; far less than what the U.S. military originally paid to acquire the beasts earlier. The sales were all approved by the Major General Montgomery Meigs, who hoped the camels might fare better with civilians.

By all accounts, the animals lived good lives. Many gave rides to children, while others worked as pack animals. The camels became familiar sights, not only in the Southwest but as far away as British Columbia. Interestingly, Robert E. Lee encountered the camels while serving as temporary commander of the Department of Texas before the Civil War. Later, a young Douglas MacArther saw “an old Army camel.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The last of the original Army camels, Topsy, reportedly died in April 1934 in Los Angeles. He was 80 years old. However, other accounts of camel sightings, including the offspring of the original 70 camels, continued for decades as a legacy of the American military camel.

This article is from the Summer 2020 issue of Guns of the Old West magazine. Grab your copy at OutdoorGroupStore.com. For digital editions, visit Amazon.