The very first firearm ever manufactured by Samuel Colt was a rifle!

Although Colt is known the world over for its legendary handguns, it has an equally impressive history in long arms dating back to the 1830s, the Mexican-American War in the late 1840s and the Civil War. The repeating or revolving-cylinder rifle had its origins in Paterson, New Jersey, around 1835.

In the 1830s, the U.S. military was armed with single-shot flintlock and percussion-lock pistols, smoothbore and rifled muskets, and percussion-lock, double-barrel shotguns. Samuel Colt proposed to replace them all with multi-shot, revolving-cylinder weapons—from belt pistols to shotguns—all based on his original 1835 and 1836 patents for the revolving-cylinder pistol. While Colt’s investors had been anticipating a small pocket-model revolver to be introduced, young Sam dismayed his New York backers with a massive revolving rifle. The first gun put into production at Paterson was the No. 1 Ring Lever rifle. Both the No.1 and improved No. 2 models are fascinating designs.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

First Options

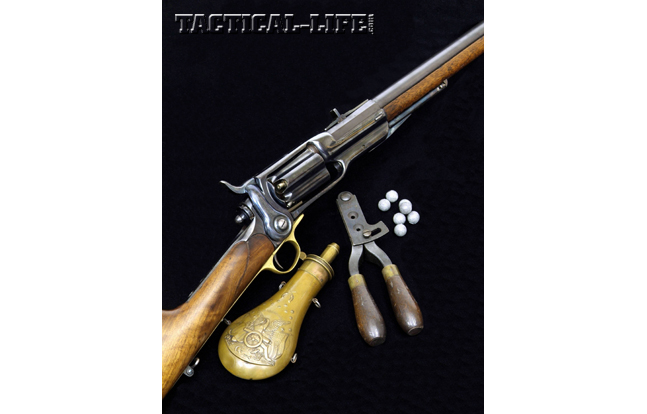

The No. 1 Ring Lever was available in a wide variety of chamberings, including .34, .36, .38, .40 and .44 calibers, and with eight- or 10-shot cylinders. The No. 1 was generally offered with one barrel length, 32 inches, though shorter lengths were made, and some were later restocked as horse pistols carried in pommel holsters, with their barrels shortened to 10.44 inches. Within the first model series, it is estimated that no more than 200 were manufactured. Replaced by the No. 2 model, the Paterson was now available in eight- and 10-shot, .44-caliber versions and two standard barrel lengths, 28 and 32 inches. More popular than its predecessor, a total of approximately 500 were built between 1838 and 1841.

The most important feature of the No. 2 was a loading lever attached to the right side of the barrel lug to facilitate the rapid loading of each cylinder chamber without the need of a separate rammer, as was traditionally used on single-shot muskets. The No. 1 models could also be refitted with a lever but did not come equipped with them. Loading the No. 1 revolving rifles was generally accomplished by removing the barrel, placing a loading tool in the cylinder arbor notch and then loading each chamber. The attached loading lever on the No. 2 made this a much faster process and earned Colt some modicum of praise from the military, as the barrel no longer had to be removed to load the cylinder.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

During their production runs, numerous changes were made to the No. 1 and No. 2 models regarding their cylinder designs, particularly the removal of the topstrap from the No. 2, creating the “open top” design that would become standard Colt fare until 1873.

As with his Paterson pocket and belt pistols, which were also introduced in 1836, Colt’s greatest champion was the Republic of Texas. In 1839, the Texas Army placed two orders for the No.2 Paterson revolving rifles, two lots of 50 each, in August and October. Interestingly, Colt’s later Model 1839 revolving carbine took a different design approach than the No. 1 or No. 2 models, rendering them immediately obsolete.

Model 1839 Carbine

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Doing away with the ring lever, the Model 1839 carbine introduced an external hammer. The new open-top models were chambered in .525 caliber (six shot) with square-back cylinders, attached loading levers and either 24-, 28- or 32-inch “smoothbore” barrels. This was to become the most popular of the Paterson revolving rifles, remaining in production through 1845 (under John Ehlers), thus surviving the foreclosure of the Patent Arms Manufacturing Company in December 1842. They were also sold by Samuel Colt as late as 1850 through his new Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company, established in 1847. Total production is estimated to have been 950. Of the approximately 50 carbines sold by Sam Colt between 1849 and 1853, all of these examples were purchased by Colt from the State of Rhode Island (which had ordered them through Ehlers around 1845). Colt had them refinished and most notably had the cylinders turned down, leaving them “in the white,” a trademark of Walker Colt and early Dragoon revolver cylinders. These examples are regarded today as 1839/1848 Paterson revolving carbines.

The Model 1839 was essentially a very big Paterson pistol, far simpler and more rugged in design than the No.1 and No. 2. Lighter in weight than the Ring Lever models, which averaged 8.5 pounds, the Model 1839 carbine tipped the scales at 7.69 pounds. Most examples found today have the attached loading lever, although early carbines were manufactured without them. These specimens came with the Paterson combination loading tool and barrel kick-off tool (shaped like a large question mark). In addition, records show that approximately 50 carbines were produced with rifled rather than smoothbore barrels, giving them greater accuracy.

The Model 1839 was an elegant evolution of Colt’s revolving rifles and could also be ordered as a 16-gauge shotgun. This had been the advantage of the smoothbore barrels, as the rifles could also double as six-shot scatterguns. In fact, the Colt repeater predates the six-shot Winchester Model 1887 lever-action shotgun by nearly half a century!

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

A number of Model 1839 carbines were also converted to large-caliber pistols in the early 1840s by private gunsmiths. Though these specimens are rare, they do exist. Far more massive than even the Walker, these rare carbine conversions were, for their time, the most powerful revolvers in the world.

Sidehammer Time

There had been a handful of experimental revolvers designed by Sam Colt and inventor Elisha King Root, who was placed in charge of the Colt armory in Hartford. These new models had employed a topstrap (many are on display at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Connecticut), as well as various means of fixed barrels and break-open action designs predating Starr and Smith & Wesson top-breaks. The best of the early designs from Root was the Model 1855 patent model revolver, the fountainhead for a separate line of Colt pistols and rifles featuring a solid frame and unique side-mounted hammer. The prototype design had been finalized by Root and Colt in 1854, and a patent was issued in Root’s name on Christmas Day of 1855. Subsequent patents for the Root pistols (May 4, 1858) bore Samuel Colt’s name, with Root signing as witness. The Root pistols and rifles, also known as “Sidehammer” models, became eminently popular during the Civil War, particularly the long arms, which allowed a soldier to have a large-caliber rifle, a carbine or a shotgun with up to six shots before reloading. Bear in mind that Colt’s repeating rifles were in use at the same time as the first effective lever-action rifles used in the Civil War: the slow but dependable seven-shot .56-50 Spencer rifle and carbine as well as the innovative, 16-round .44 rimfire Henry repeater produced by Oliver Winchester.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Despite the Spencer’s popularity with the military (and President Abraham Lincoln), as well as the growing demand from the field for Henry repeaters, the traditional single-shot rifled musket remained the standard-issue long arm carried by federal troops during the Civil War. One has to be reminded that at the start of the Civil War neither Union nor Confederate soldiers were well armed. With 11 Southern states having seceded from the Union by May of 1861, the U.S. had only one arsenal at its disposal, the very first U.S. arsenal established in 1794 in Springfield, Massachusetts. The Confederacy had confiscated the second major federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, along with machinery and inventory. Thus the Ordnance Department had to establish manufacturing through independent arms-makers very early in the war, as well as import additional arms from Europe. The U.S. Army’s accumulation of existing rifled muskets from the 1840s and 1850s was backed up by a considerable cache of Colt’s Model 1855 revolving rifles and carbines. In addition to those, in 1862 Colt delivered as many as remained in inventory, and the government purchased all that could be supplied by Northern retailers B. Kittredge & Co., C.J. Brockway and New York dealer Schuyler, Hartley & Graham, including early sporting models of the Root rifle.

Check out this article about The Colt 1851 Navy Revolver!

The Root Sidehammer model rifles were chambered in a variety of calibers: .36, .44 and .56. The first two chamberings were six-shot, the latter five-shot. The military rifles and rifled muskets were chambered in .44, .50 and .56 caliber, the latter being a five-shot. A full-stock sporting rifle was offered in chamberings from .36 through .56 calibers, the latter once again limited to five shots. Many federal soldiers were armed with the Sidehammer Artillery Carbine, which was fitted with a 24-inch barrel and a full forearm. The revolving carbine was offered in the same chamberings as the sporting rifle. Smoothbore shotgun versions were all five-shots in either 10 gauge (.70 caliber) or 20 gauge (.60 caliber). Frame sizes on all Sidehammer revolving rifles and shotguns varied according to caliber or gauge. Colt manufactured 1,100 revolving shotguns in 10- and 20-gauge chamberings between 1860 and 1863.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Long Range

The infantry version of the Model 1855 was known as the “Military Rifle.” Fitted with a full-length forearm and a 31-inch barrel, it was manufactured from 1856 to 1864. The barrels were fitted with a nickel-silver, half-moon front sight and a folding leaf rear sight with 100-, 300- and 500-yard graduations. Although the design was six years old at the start of the Civil War, soldiers armed with a Colt Sidehammer carbine or Military Rifle had an advantage over those armed with single-shot carbines and muskets. At the onset of hostilities, only the Colt Model 1855 Sidehammer rifles, muskets and carbines were in abundance—especially the Military Rifled Musket in particular, which gained early fame in the hands of Colonel Hiram Berdan’s 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters. The old but remarkably accurate and reliable Colt repeaters were used by the U.S. Sharpshooters until 1862, when they were replaced with more accurate single-shot Sharps breechloading rifles capable of making 1,000-yard shots. Berdan’s Sharpshooters, armed with both Colt and Sharps rifles, were instrumental in the Union’s victory at Gettysburg in 1863. The Root models have become highly collectible and represent one of the most interesting long arms used in the Civil War. The most unusual, however, was the LeMat.

The South’s LeMat

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Southern troops, at least the regulars, had all been U.S. troops before the start of the Civil War, and many Southern garrisons had supplies of older arms from the 1840s and 1850s, thus it was not uncommon for Confederate soldiers to be armed with early Colt revolving rifles made in Paterson, New Jersey, as well as Root’s Model 1855 carbines, rifles and shotguns produced in Hartford prior to the war. The South also had its own unique revolving long arm, and like the Colt, it too was based on a pistol.

This nine-shot, .42-caliber masterpiece of firearms design was the work of a medical doctor, Jean Alexandre Francois LeMat, who, at the age of 22, having completed his medical training and residency as a surgeon and assistant medical officer at the military hospital in Bordeaux, France, moved to the U.S. in 1843. After establishing a practice in New Orleans, in 1849 he married Justine Sophie LePretre, the cousin of U.S. Army Major Pierre-Gustave Toutant Beauregard, the very same Beauregard who would lead the bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in April 1861 that began the Civil War.

Among young Dr. LeMat’s inventions was his patent for rifling cannon barrels and an innovative nine-shot revolver with a shotgun under-barrel, developed in 1856 with Beauregard’s assistance. Three years later, the very first examples of the LeMat Grapeshot revolver were manufactured in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, by gun-maker John H. Krider. The original invoice for the prototype revolver, dated October 24, 1859, and in the amount of $208.80, can be found at the University of Louisiana. Though designed and prototyped in America and initially presented to the U.S. military for evaluation by Major Beauregard, events of the year to come would lead to the LeMat being manufactured in France, Belgium and London. The guns were delivered to Richmond, Virginia, by hired clipper ships flying foreign flags. Many of the cargo vessels had to run Union blockades, and over the course of the war a few didn’t make it, with ship and cargo being sent to the bottom.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Among the LeMat variants produced in France and Belgium during the war were a handful of rifle-length revolving arms and rifle-length pinfire (breechloading) LeMats that were built in Belgium. Pinfire revolvers were being imported into the U.S. from Europe by both the Union and Confederate states during the Civil War. The LeMat Pinfire carbine was extremely scarce, and the example shown in this article has an 18.75-inch, part-octagon, part-round barrel and walnut stock. The cylinder and upper barrel are chambered in .44-caliber pinfire; the lower barrel is rifled and chambered in .56-caliber percussion.

Remington’s RUN

Remington had viewed the Colt revolving rifles and carbines as something of a success in the 1850s, although Remington, along with every other American arms-maker, had been prevented from manufacturing revolvers by the Colt patent, which did not expire until 1857. Remington introduced its first revolvers in 1857 and began manufacturing revolving carbines in the 1860s. Towards the end of the Civil War, the U.S. Army had procured a small number of Remington’s revolving-carbine versions of its .44-caliber Army and .36-caliber Navy revolvers, although Remington didn’t build more than 1,000.

In 1868, Remington started converting its percussion revolvers to .46 rimfire and .38 centerfire metallic cartridges. Remington had to pay a $1 royalty for each gun built to Smith & Wesson, which had held the patent rights to both the bored-through cylinder and breechloading revolver since 1855. Remington had been the recipient of patent blockades on both ends, first in manufacturing revolvers by the Colt patent and then building cartridge conversions by the White patent owned by S&W, thus the New York arms-maker chose to buy its way into the market by paying a royalty to S&W. When it expired in 1869, S&W and inventor Rollin White sought a patent extension but were refused. By then the self-contained metallic cartridge and handguns built to fire it were on the way to eclipsing the Civil War-era cap-and-ball revolver, just as the Henry lever-action rifle and new Winchester Model 1866 were displacing the single-shot rifle. The last Remington revolving carbines were produced around 1872. Today, only around five of the large-caliber (.46 rimfire) conversions are known to exist.

Brief Legacy

By the time Winchester unveiled its benchmark Model 1873 lever-action rifle, the once-innovative Colt repeating rifles and carbines that had been regaled in war and on the western frontier since the 1840s, along with the handful of Remingtons and LeMats manufactured, all had become antiquated—relics of the past left to those who either had an eccentric fondness for them or little means of acquiring anything newer. For one brief period though, the revolving rifles, carbines and shotguns were the most advanced military long arms the world had ever known.