“Can a dropped gun go off?” is a frequently asked question in the gun world. The short answer is “yes.”

The gun that goes off when dropped is a staple on TV and in the movies. Those fictional venues often depict it happening with guns that actually don’t go off when dropped. That makes gun-wise moviegoers of our generation just roll their eyes at the liberties Hollywood takes with reality. Unfortunately, that “you can’t believe Hollywood” mentality can blind us to the fact that a dropped gun can actually go off.

Usually, the culprit is a phenomenon called “inertia discharge.” It occurs with, say, a semi-automatic pistol whose firing pin “floats” in its channel without a mechanical lock. If the gun is struck sharply in a direction parallel with the pin’s travel in that channel, it can come forward enough from inertia to discharge. This may occur if the gun is dropped on its muzzle. In this case, the bullet generally strikes what the muzzle hit and causes little damage unless it has hit a second-story floor in a multi-floor building, in which case the bullet can pass downward through the floor and into the room below. It may also occur if the pistol is dropped on the rear of its slide or receiver, the spur of its hammer, etc.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Bathroom Incident

What I’ll call Case One occurred in June 2009 in Tampa, Fla. A lady was shot in the leg while in a stall of a ladies’ room at a local hotel. Says the news source, “Police said the woman in the next stall accidentally let her handgun slip out of her waist holster, and the weapon discharged when it hit the ground…The gun belonged to Debra Monce of Land o’ Lakes. She has a concealed weapons permit for the small-caliber handgun, but the case has been referred to the State Attorney’s Office for review.”

That’s the last news I had on the matter at this writing. The prosecutor’s office has many options, one of which is charging Reckless Endangerment. And, is the lady who dropped the gun open for a lawsuit alleging negligence with injury resulting? Well, what do you think?

The news report stated that the victim sustained only “minor injuries.” That’s good news for all concerned.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Not All Guns Are Built the Same

What was not explained in the report was exactly what specific handgun was involved. We know that certain handguns have been associated with this type of impact-generated unintended discharge over the years. Derringer-type pistols with external hammers, for example. Old-fashioned revolvers allow the hammer to be driven forward by the impact on its rear portion, forcing the firing pin against an underlying primer with enough impact to discharge the cartridge. Many semi-automatic pistols, not just cheap or junky ones, do not have any sort of mechanical barrier in the mechanism that acts as a firing pin lock or block.

Single-action “frontier-style” revolvers were known since the 19th century to be vulnerable to this. That’s why in the Old West it was almost universally understood that one should leave the chamber that is under the hammer empty. One of the West’s most famous peace officers, who most certainly should have known better, had a “near-miss” through just that dynamic.

Wyatt Earp’s Dropped Gun Incident

Case Two: No less a legendary lawman than Wyatt Earp experienced a dropped gun accidental discharge. In what is probably the most detailed biography of Earp, Wyatt Earp: A Biography of the Legend, veteran historian and acknowledged gun expert Lee Silva researched a news clipping from the time, that he quoted in Volume 1: The Cowtown Years.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Silva found it in the Jan. 12, 1876 edition of the Wichita Beacon. It read, “Last Sunday night, while policeman Earp was sitting with two or three others in the back room of the Custom House Saloon, his revolver slipped from its holster, and falling to the floor, the hammer which was resting on the cap, is supposed to have struck the chair, causing a discharge of one of the barrels (sic). The ball passed through his coat, struck the north wall then glanced off and passed out through the ceiling. It was a narrow escape and the occurrence got up a lively stampede from the room. One of the demoralized was under the impression that someone had fired through the window from the outside.”

Silva also gained access to some of Earp’s correspondence with his compliant biographer, Stuart Lake, in the late 1920s. He had apparently admitted that it happened when Lake asked him about it, and in a note asked Lake to leave out “the little affray with the chair.” Lake complied.

And, when Lake’s Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal did come out a few years later, Earp was emphatically quoted in it as saying professionals would never carry a live round under the hammer of a single-action revolver.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Way of the West

In the early 1950s, “adult Western” movies like the great High Noon and cowboy shows on TV created a new interest in the single-action six-guns of the old frontier. Bill Ruger led the charge to create them. He began with his .22 caliber Single Six revolver in 1953. Following two years later with the first of his center-fire Blackhawk series in the same vein. Though sporting improved sights and a stronger mechanism (including, for example, coil springs), Ruger left them otherwise true to the original Colt design. Colt soon began producing a second generation of the original, their Single Action Army. Great Western and other manufacturers got into the game, too.

Newlywed Incident

Unfortunately, American common sense had apparently deteriorated since the days of the pioneers. A spate of accidents occurred in which recently manufactured single-action revolvers were dropped, discharged, and hurt or even killed someone because the user had carelessly left a live round under the firing pin. Taking just one of these as an example, Case Three involved a newlywed on his honeymoon. The newlywed arose from the marital bed to get a bite to eat, and felt a need to stuff a Blackhawk loaded with six rounds in the flimsy waistband of his pajama bottoms. As he bent forward to reach for some food, the gun predictably fell out and landed on its hammer, hard enough to discharge a Mag round that caused a grievous and tragic wound. Predictably, Ruger was sued.

The Ruger Redesign

After spending millions on such legal affairs, Bill Ruger supervised a redesign. Hence the New Model Ruger Single Action series was born. It used a transfer bar mechanism to prevent any sort of inertia fire or dropped gun discharge. It also rendered the new guns safe to carry with all chambers loaded. The company also offered a free retrofit of parts that would have the same effect on the older models, an offer that stands today. This, of course, cost millions more to Ruger.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Some might say, “Well, that’s Ruger’s problem.” I dunno about that. If you’re reading this publication, I suspect you know your guns. Let’s say you lend an old Colt Single Action Army, or a now-collectible old three-screw Ruger from the early days that doesn’t have the factory upgrade, to a friend or relative. Let’s further suppose that you forget to tell him, or he later claims he doesn’t remember you telling him, that it was not safe to carry it with a live round under the hammer. And, the final supposition: he drops the gun, it goes off, and he is permanently paralyzed.

He and his family look for people to sue. Well, they’ll file suit against the manufacturer, of course. Do you doubt for a moment that one of the more money-hungry and less-scrupulous members of that institution called “plaintiff’s bar” might also decide to name you as the defendant in a lawsuit? It’s definitely something for the cautious gun owner to think about.

Discharges With Dropped Semi-Automatics

This column began with a discharge from a dropped semi-automatic pistol that caused a gunshot wound to a third party. Fortunately, her injuries were described as minor by the investigating authorities. Let’s look now at a dropped gun incident with much more tragic results. We’ll call it Case Four.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Firearms journalism recently experienced the tragic death of one of our own. Many of you have read the excellent writing of Steve Malloy. He was a regular writer for SWAT Magazine. Here are some excerpts from his memorial, as printed in the August 2009 edition of SWAT and written by editor Denny Hansen.

Denny wrote, “Longtime SWAT Magazine Contributing Editor Steve Malloy was killed in a tragic shooting accident at his home on April 16. As best as can be determined, Steve had a pistol in his waistband and when he bent over to tie his shoes, the pistol fell onto the floor and discharged. The bullet struck Steve in the chest. He was found in the garage, apparently trying to leave the home to summon aid.”

He continued, “When dealing with things of a tactical nature, Steve was the epitome of the word ‘professional.’”

Denny Hansen appropriately titled his memorial page to Steve Malloy, “We Are Diminished.” It seems that he couldn’t have chosen better words. Unlike Denny, I didn’t get to know Steve Malloy personally, and that seems to be my loss. By all accounts, he was a fine man, a good cop, and a total professional. His family lost a loving husband and father. The rest of us lost a genuine expert who busted his butt to give us the best evaluations of life-saving emergency rescue equipment possible.

Being Careful with Classics

I’m told the weapon in question was a 1903 Colt Pocket Model pistol, carried with a live round in the chamber. It was a classic old gun that is revered by those who appreciate fine firearms. The 1903 .32 and the 1908 .380 Pocket Models have a long and honored history. Such guns were issued to Generals like Patton and Eisenhower in WWII, and to OSS personnel in the same time period. My grandfather shot an armed robber in self-defense early in the 20th century with a 1903 Colt .32. That particular gun was the first semi-automatic pistol I ever fired before my age had two digits in it. Slim and compact, comfortable to carry, sweet of trigger pull, and deadly accurate and reliable. It was the kind of pistol a “gun guy” like Malloy would appreciate.

It also did not have a secured firing pin and was not “drop-safe” against inertia fire. You don’t carry a 1903, so it doesn’t matter? Well, if you carry a 1911, it does matter, because both mechanisms were designed by John M. Browning and are remarkably similar. You aren’t going to ever drop your gun? Good that you’re the first perfect human who’s immune to error. It’s safe to say that neither you nor I are perfect humans incapable of making a mistake. And these old Colt designs are not by any means the only autopistols that are not “drop-safe”!

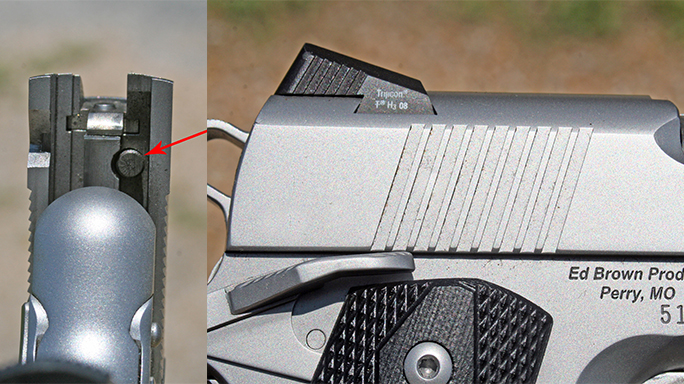

Internal Firing Pin Locks

Let’s look inside the guns in question. Not until the 1930s did the 1911 pistol get a positive internal firing pin lock, the Swartz safety. Colt history students know that it was so complex and expensive to manufacture that after production was stopped with the coming of WWII, Colt never offered that option again. Not until the Series ’80 modification were Colt 1911s truly “drop-safe” again.

The 1911, in its many incarnations from many manufacturers, is sometimes drop-safe and sometimes not. The Colt Series ’80 and later Series ’90 are mechanically drop-safe. This is thanks to an internal firing pin lock that is actuated by the trigger system. Para USA pistols use the same safe system, having licensed it from Colt. The Sig Sauer 1911 pistols use it too. A number of years ago, the great modern gun designer Nehemiah Sirkis resurrected the Swartz internal firing pin safety concept, which works off the grip safety that is standard on 1911s, for Kimber.

Playing it Safe with “Drop Safe”

If your Kimber has a Roman numeral “II” suffix on its model number, it is so equipped. It works better today because modern CAD-CAM engineering and manufacturing make it more cost-effective to produce. Smith & Wesson uses a similar concept on their SW1911 pistol. Other companies chose to go the “drop-safe” route with light firing pins and extra-heavy firing pin springs. The momentum of impact couldn’t send a heavy pin forward against light spring resistance and into the base of a primer with enough force to make the weapon fire. Any of these systems can work. 1911 experts say firing pin springs should be changed every 3,000 to 5,000 rounds to prevent spring fatigue and weakening.

Conclusion

Bottom line? The criminal and civil liability potential of a “dropped gun discharge” from a firearm that is not “drop-safe” are obvious, and just as obviously unacceptable. None of us are “cooler” or “more professional” than Wyatt Earp or Steve Malloy. If it happened to them, it can happen to any of us.

This column is respectfully dedicated to the memory of Steve Malloy. He dedicated himself to teaching good people how to stay alive and keep others alive.