Introduced in 1899 as the Hand Ejector in calibers .32-20 and .38 Long Colt, Smith & Wesson’s Military & Police would soon be the first revolver chambered for the .38 Special cartridge. That would be its primary caliber from then on, and the M&P revolver would be largely responsible for the huge and enduring popularity of the .38 Special round.

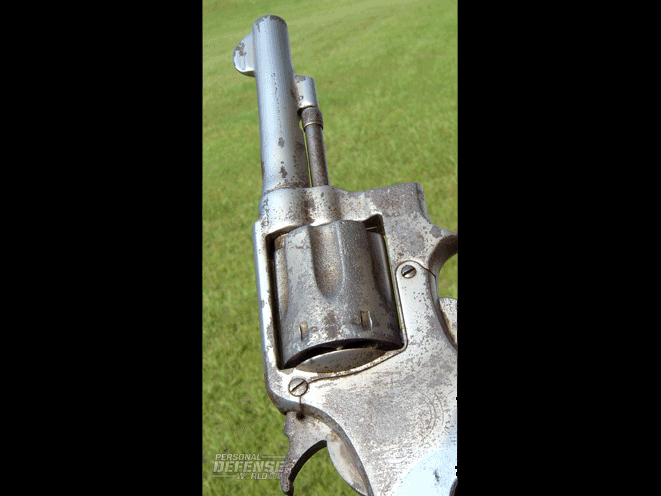

The First Model, as collectors know it now, had a round butt. It didn’t have a locking lug at the front of the ejector rod, but that was added in 1902 with the Second Model. A square butt was added at the same time, which would be the most popular configuration. By 1915, there was a snubnose version with a 2-inch barrel.

M&P Warriors

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

By 1942, Smith & Wesson would produce its millionth M&P revolver. Throughout World War II, the company manufactured a huge number of them in .38 Special. (George H.W. Bush, later to become President of the United States, was carrying one when he was shot down in the Pacific during that conflict.) Before WWII was over, S&W also manufactured more than a half-million M&Ps for the British chambered in .38/200. All of those WWII guns were known as Victory Models, made quickly with smooth walnut stocks instead of S&W’s usual fine checkering, and with gray Parkerized finishes instead of the lustrous commercial blue that characterized an American cop’s or citizen’s S&W M&P.

RELATED: Smith & Wesson M&P Combo Training

The post-WWII years saw subtle changes in the action mechanism, with S&W going to a shorter version, which inevitably resulted in collectors calling the older models “long action” guns. S&W’s “Magna” stocks, upswept toward the horn at the back of the grip frame, distributed recoil more comfortably to the web of the hand. Originally created for harder-kicking guns like the .357 Mag “Registered Magnum” of 1935, these stocks improved the handling of the M&P revolvers when added during the postwar years.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In the late 1950s, two major events occurred with the Smith & Wesson M&P line. S&W began offering an un-tapered “heavy barrel,” 4 inches in length, which most felt improved handling and recoil control, adding about 3.5 ounces of weight up front. In roughly the same timeframe, S&W started assigning numeric designations to its handguns. The Military & Police became the Model 10 in its standard format of all-steel construction. The aluminum-frame Smith & Wesson Airweight version introduced in 1952 was designated the Model 12.

Time marched on. The first and only large-frame, fixed-sight M&P, the Model 58 in .41 Mag, came out in 1964. Later came the Model 64, a standard K-frame M&P .38 Special stainless steel, an instant hit in the police community. In 1974, introduced the Model 13, a heavy-barrel Model 10 chambered for the .357 Mag that had begun as a variation produced at the request of the New York State Police. This would soon be augmented with a stainless variation, the Model 65. The Model 347 was offered in 9mm, but didn’t last long. A 3-inch heavy barrel would prove to be a popular variation in both .38 Special and .357, and in both chrome-moly and stainless steel variations; a 3-inch-barreled Model 13 would be the last standard-issue FBI service revolver before the Bureau switched to semi-automatics. Midway through the first decade of the 21st century, the one and only small-frame (J-frame) Military & Police revolver appeared, the M&P340 in .357 Mag. It remains in the S&W catalog.

Standards & Variants

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Military & Police Target came out almost as soon as the original Hand Ejector. It was simply the same gun with adjustable sights, usually fitted with a 6-inch barrel. It would later become known as the K-38 with that barrel length, and the Combat Masterpiece with either a 2- or 4-inch barrel. These were .38 Specials predominantly, though some would be produced in .32 Long as “K-32s,” now cherished by Smith & Wesson collectors.

RELATED: Smith & Wesson M&P45C

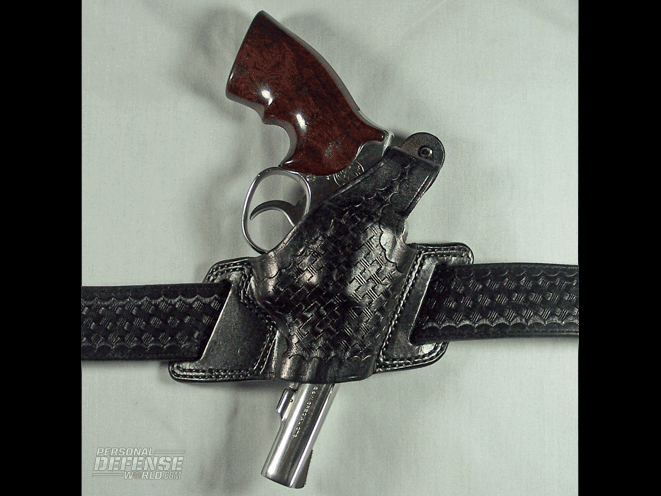

The true Military & Police is a fixed-sight handgun. Over 115 years they have been produced in barrel lengths of 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 inches. There were also special orders for barrel lengths of 2.5, 5.5 and, extremely rare, 6.5 inches. For decades, the standard-issue Detroit Police service revolver was a nickel-plated .38 Special M&P with a 5-inch barrel. Until they adopted the semi-automatic S&W Model 5946 9mm, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police for the most part carried blued Model 10s with specially ordered 5.5-inch barrels.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

While the .38 Special was over-whelmingly the most popular caliber for the M&P, we’ve already noted that these fixed-sight revolvers were produced in .38/200 for overseas use, .38 Long Colt (the standard U.S. military caliber in 1899 when it was introduced), .32-20 and 9mm Luger. S&W historian Roy Jinks has written that a bit less than 5,000 Military & Police revolvers were produced in .32 Long. And there was the N-frame M&P in .41 Mag, the Model 58.

There were also fixed-sight M&P revolvers manufactured in .22 LR, primarily for training purposes, but they are extremely rare. Though never catalogued, these were known as the Model 45 after S&W’s 1957 switch to numerical designations. The oldest fixed-sight M&P .22s I know of were produced in the early 1930s for the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, all with 6-inch barrels. There were no more than three-dozen in the production run; fewer than half of them are known to still exist. I have the good fortune of owning two, and, yes, they still shoot well.

Even rarer than that is the one-of-a-kind snubnose Military & Police .22 custom-made by Smith & Wesson in 1946 for the great Col. Rex Applegate. It now resides in the gilt-edged collection of one of the nation’s leading S&W collectors.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Becoming A Classic

In one sense, a gun is classic if it’s hugely popular—the Colt/Browning 1911 pistol, the Colt Single Action Army and the Smith & Wesson Military & Police all qualify. In another sense, longevity is a qualifier for the title of “classic,” and 115 years will easily accomplish that. But in a deeper sense, we have to understand why something earned its popularity. In every case you’ll find ergonomics, reliability and suitability to the task at the base of their classic status.

RELATED: Deep Cover Smith & Wessons

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Ergonomics: In the K-frame revolver, Smith & Wesson hit on something close to perfect for the hand of the average adult male. While many women, particularly those with small hands, had problems with the K-frame M&P, many did not. And, while many big men with huge hands found the little J-frame too small to do their best shooting with, you’ll rarely find even the most ham-handed man saying the same thing about a K-frame like the M&P.

Reliability: The S&W K-frame simply ran and ran, so long as you didn’t beat it to death with heavy loads. If shot heavily, it turned out to be a relatively short-lived gun when chambered for the .357 Mag cartridge, vastly higher in pressure and more violent in recoil than the late 19th century loads it had been built for. This is why K-frame .357 Mags are no longer produced by Smith & Wesson. In .38 Special, though, they stood up to con-stant qualification firing even with the +P loads of the ’60s and ’70s that brought the .38 up off its knees and made it an acceptable fighting cartridge. Constant +P pounding will require more frequent repair, but they still last. I own a 4-inch-barreled Model 13 that has been rebuilt twice due to heavy use with 125-grain magnum rounds, but as worn as it looks, it still “groups tight and runs right.”

Suitability: The Military & Police was and is extremely accurate; 1-inch groups with the best ammunition at 25 yards are more norm than exception. The only real structural difference between the police service M&P and the target-grade K-38s were the adjustable sights, the (sometimes) fancier finish and the adjustable trigger stops found in the latter. In most of the cartridges it was chambered for, including the .38 Special that defined the M&P, its recoil was controllable. Depending on the barrel length, it was suitable for outdoorsmen, uniformed cops and concealed carry. It was almost impossible for normal wear and tear to knock its fixed sights out of point of aim/point of impact coordinates.

21st Century M&Ps

Today, when you say “Smith & Wesson Military & Police,” there’s a whole generation that visualizes a semi-automatic service pistol with a polymer frame. The semi-auto M&P is certainly a fine gun; half a dozen of them reside in my gun safe, and none gather moss. But for my generation and those who preceded it—and probably at least one generation after that—“Smith & Wesson Military & Police” defines a medium-size, six-shot service revolver.

RELATED: Sibling Harmony – Smith & Wesson’s M&P40 and M&P22

Soldier or sailor, cop or guard, the institutional user of handguns who is not “into guns” on his or her own time will find it hard to accidentally discharge a double-action revolver, particularly one that is double-action-only. From Miami to New York City to Montreal, there was a time when police departments learned to specify that their Smith & Wessons fire only in double-action mode. “Administrative handling”—routine loading, unloading, cleaning, etc.—simply offers less margin for error with a double-action revolver than with a semi-automatic pistol.

Many people in the private sector do not have the physical strength to vigorously manipulate the slide of a semi-automatic pistol. The revolver elimi-nates that problem.

Any firearms instructor will tell you that jerking the trigger is probably the single most common “marksmanship problem” for the shooter who is trying to become more accurate. For decades, I’ve told my students to buy a good double-action revolver like the S&W M&P and spend some time learning to manipulate its trigger in double-action mode. It teaches the shooter how to distribute trigger pressure. One phrase I’ve constantly repeated to my students is, “A double-action revolver trigger will teach you to shoot your autopistol better.” Countless other instructors say the same. The reason: It’s true.

For much of its existence, this revolver’s major shortcoming was that it was chambered for a cartridge experienced street cops considered a feeble one that would make their wives widows by failing to work when they needed it. By the 1970s, +P hollow points like the all-lead, 158-grain FBI load had changed that. With today’s more effective ammunition, the .38 Special is certainly a viable option.

Ironically, on the S&W website today, the only M&P revolvers are non-K-frames: the M&P340 series of J-frames and the eight-shot M&P R8 in .357 Mag, the second N-frame to carry the M&P designation and, since the pre-K-38 M&P Target, the only revolver to bear that name while wearing adjustable sights.

But gun shops and gun shows are rife with the original classic M&P revolvers. If you don’t have one, it would be worth your while to acquire one, if only because it has earned the name Classic with a capital “C.”

For more information, visit smith-wesson.com or call 800-331-0852.

This article was originally published in COMPLETE BOOK OF HANDGUNS 2014. Subscription is available in print and digital editions below.