The defensive firearm is, by definition, going to be used under stress when the time comes for it to fulfill its purpose. The fundamentals of marksmanship that you learned in the calmness of a classroom and on the training range may go out the window if the training did not encompass something I’ll call “stress inoculation.”

Trainers speak of four levels of competency when it comes to important physical skills. At the bottom is unconscious incompetence, where a person doesn’t know what he is doing and hasn’t yet realized he doesn’t know he’s doing. He is set up for failure, and should there be a life-or-death need for the skillset in question, he will likely die unless he is awfully lucky.

Next up is conscious incompetence, where the person realizes that he doesn’t know what he is doing. This is somewhat more manageable because such a person tends to be hyper-cautious, won’t get in over his head and will hopefully train until he reaches the next level. That level is conscious competence—the realization that if he thinks about what he is doing, perhaps only for an instant, he can do what needs to be done.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

At the pinnacle is unconscious competence. The person has performed the skillset required so many times that, given the stimulus, he can carry out the response on autopilot without thinking about it.

Unconscious competence—called “in the zone” by some sports practitioners and “the Zen state” by some in other disciplines—is what we all seek. Unfortunately, none of us can guarantee perfect autopilot performance on demand. I use the “autopilot” terminology when I teach because people can relate to it easily. Any pilot knows that autopilot is useful technology when the skies are calm, but when the aircraft is in trouble, it’s time to turn it off and go to the “manual override” of conscious competence. Thinking about what you are doing will bring you back on course.

That said, though, having the skills dialed into an autopilot level will leave your mind free to deal with non-physical things, such as the absolutely critical aspect of deciding whether or not you need to shoot to survive. Let’s explore that in a bit more depth.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Fight Or Flight

We know that certain things will trigger the “fight or flight” response—the high level of body-alarm reaction that was described before World War I by Dr. Walter Cannon of the Harvard Medical School. In such a situation, the body will instantly release epinephrine (aka adrenaline), which can increase your physical strength to an almost superhuman degree, as well as norepinephrine and endorphins, which will briefly make us almost impervious to pain.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

- RELATED STORY: Concealed Carry At Home – 3 Must-Know Cases

A side effect of this “adrenaline dump” may be violent tremors. This is why, for decades now, I have forced my students to shoot with their hands deliberately trembling to show them that they can do it when SHTF and still score neutralizing hits.

Studies show that, more often than not, we will experience such altered perceptions as tunnel vision and auditory exclusion. This means that we may no longer perceive a second opponent on the periphery of the initial attacker we are focused on, and we may not hear someone shouting a dire warning like, “Look out, there’s another one coming behind you!”

Yes, this complicates things. We are unlikely to see that which we are not looking for (inattentional blindness), nor hear that which we are not listening for (inattentional deafness). This is why we are all taught to scan a dangerous scene as soon as we think the initial opponent is down, and to listen as well. This is also why it is so valuable to have the skillsets down to the point where we can perform them on autopilot, to free our cognitive attention to gather intelligence as to what we must do next, both to survive and to not make a bad situation worse.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Lessons Learned

Having studied this element of the self-defense discipline for more than 50 years, and having done so professionally for well over 40, let me offer some points that have stood out again and again from the lessons gunfight survivors learned—lessons so important that they virtually scream for the attention of all of us who carry guns to protect the innocent, including ourselves.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Accept that a crisis can actually happen. Too many good guys and gals, including those who wear badges, apparently think, “It will never happen to me.” I will never forget the harbor patrol officer who thought he was a ranger of the waters and a friend of the boaters, and when invited by brother officers to attend a Calibre Press “Street Survival” seminar, replied, “Naw, that’s for you—you’re cops.”

The day came when a psycho who hated authority figures saw the harbor patrol officer in his uniform near the boardwalk, targeted him and came at him with a knife, screaming that he would kill him. By the time the harbor patrolman got his gun out and fired one ineffectual shot, the knife was already in him. He died where he fell. He couldn’t get his gun out in time.

There were no wear marks on the security holster he had bought from his uniform allowance some six months beforehand, showing that he had never practiced with it, and although there was ample warning beforehand, the witnesses said he never even reached for his gun until the attacker was on top of him. His self-image as “not really a cop” had left him ignorant of the fact that, as a uniformed embodiment of society and all its powers, he had become a lightning rod for any anti-social, anti-authoritarian rogue who might be seeking a homicidal outlet for his hostility.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Have a mental program to respond. No, you can’t practice everything 3,000 to 5,000 times—the figures often quoted as necessary to perform a complex psychomotor skillset on autopilot. But if you have visualized yourself doing it and strongly programmed your mind that given this stimulus, you will perform this response, it will be there in that computer that lives between your ears, and is likely to come up when you ask that computer for the response to the given stimulus. I can introduce you to a person who twice survived what would have been fatal car crashes because—having been profoundly influenced at a young age by someone who had survived one—he did in two incidents nine years apart what he had programmed his brain to do in such a situation, even though he had never practiced it even once beforehand.

In the infamous FBI shootout in Dade County, Florida, on April 11, 1986, three of the agents experienced severe hand/arm wounds and still needed to return fire. None had been trained beforehand how to reload or work a pump shotgun with just one hand. Two men with empty revolvers were helpless when they were subsequently shot and permanently injured. A third, who figured out on the fly how to work a Remington 870 shotgun with one hand, was able to finish the fight and kill the two cop-killers, and he even had to fall back to his service revolver to accomplish that. Today, wounded-officer response techniques are taught routinely, and we can all learn from this.

Stressful Training

Training should replicate whatever emergency experience you are training for as much as possible. That training is available today for armed citizens as well as for cops and soldiers. Some high-tech shooting ranges offer simulations where you are placed in front of a screen and the situation unfolds in front of you in real time. Look around and see what’s available within striking distance for you.

- RELATED STORY: 5 Shooting Drills To Maximize Speed, Accuracy and Power

Training with non-lethal training ammo, such as Simunitions, isn’t cheap, but can be had if you do a Google search for what’s available in your area. It’s live-action role-playing pitting you against living, thinking, reacting human beings who want to shoot you in a dynamic, real-time environment. This kind of realistic training is priceless. I was doing it in the early 1970s with cops I trained with cap guns; cops in Ohio were doing it before then with cotton balls fired from primer blanks; and today we are well beyond that in terms of technology. Airsoft will do. The key is to find trainers who set up realistic scenarios.

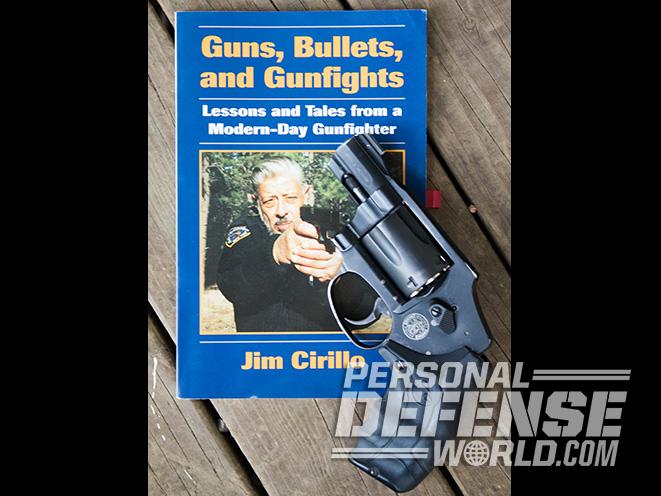

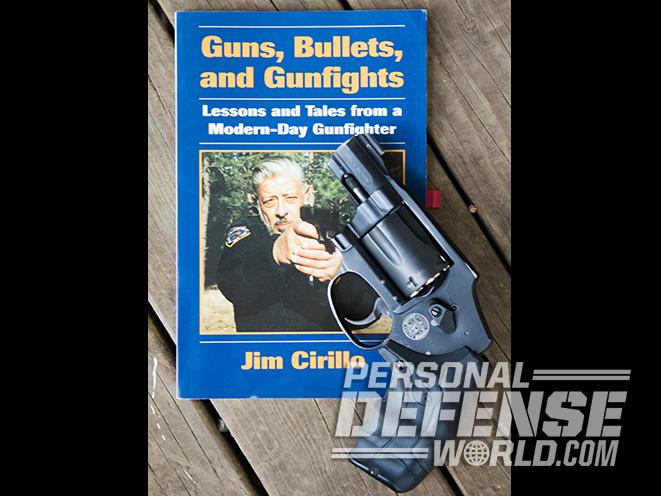

Competitive “combat shooting” is an important piece of the puzzle, too. Since the 19th century, we’ve seen that competitive shooters, whatever their disciplines, do spectacularly well in a gunfight because shooting under pressure has become the norm for them, and it leaves their minds free for critical tactical decisions while the shooting skills themselves are on autopilot. Wyatt Earp shot in informal pistol matches in the cow towns of the 1870s; the legendary Jelly Bryce got his first police job after winning a pistol match in the 1920s; national champion Charles Askins, Jr., won numerous gunfights during the 1930s and beyond; and champion shooters Jim Cirillo and Bill Allard killed many opponents while part of the NYPD Stakeout Squad. Military heroes Alvin York (WWI), Audie Murphy (WWII) and Carlos Hathcock (Vietnam) were master shooters before they went to war.

At the first Bianchi Cup in 1979, I shot on the same squad as Jim Cirillo. We were walking together from one stage of the event to another when Jim told me he had never felt this much stress in any of his gunfights. I asked him why. He replied that there weren’t all these people watching, and there wasn’t all this time to build up to it. When he wrote of his collected learning experience in his classic book “Guns, Bullets, and Gunfights,” Jim clearly stated that the members of the Stakeout Squad who were accustomed to competing with handguns in high-level competition were among the best at winning actual shootouts. Stress with a gun in their hands had become the norm for them, and they handled it superbly when the shooting was real.

My time to discuss this here has run out. Your time to learn these valuable lessons has not. The lessons I’ve mentioned have been written in blood—some by those who won and, sadly, some by those who did not.

This article was originally published in ‘The Complete Book of Handguns’ 2017. For information on how to subscribe, visit outdoorgroupstore.com.