Shooters who think “light trigger equals good trigger” – often because they’ve been jerking their trigger and the lighter pull makes them miss slightly less badly – get worked up when those who’ve actually done “hair trigger” cases in court warn against them. The light pull advocates go on the Internet and scream, “It’s all a myth! Show me a case!” Very well. We’ll show you a few of them.

Hair Trigger Liabilities: Can a Light Trigger Get You into Trouble?

The first thing to understand is that it can be an issue in both criminal cases and civil lawsuits. For different reasons.

A politically motivated prosecutor wants to get a conviction out of a self-defense shooting. He knows that Murder, for which he has to show malice, is going to be a high bar. Specifically when the defendant is a good citizen. The jury won’t be inclined to believe that such a person turned from kindly Doctor Jekyll into evil Mr. Hyde.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

However, what if the prosecutor instead charges Manslaughter, where recklessness is the key ingredient? All he must do is convince the jury that a nice person did something careless and shot the “victim” by accident, causing death.

Ever notice that you’ve heard of justifiable homicide but never heard the phrase “justifiable accident”? Since self-defense must be an intentional act, the prosecutor just needs to convince the jury you accidentally killed the guy. As a result, a Manslaughter conviction is much more likely.

And shooters know that the lighter and shorter the trigger pull is, the more easily such an accident can happen. Particularly under stress, such as in a gunpoint situation. The good news is that light triggers are easy to shoot. The bad news is…they’re easy to shoot.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Open to Civil Suits

In civil suits, the plaintiff’s counsel may also claim that you negligently discharged a “hair-trigger” gun. Thus causing the “wrongful death” in question. Why? They’re looking for deep pockets.

Most individual defendants don’t have millions of dollars in liquid assets that the attorneys can seize to satisfy the judgment if they win. However, if you shoot a home invader and have homeowner’s insurance or shoot a carjacker or road rager and have automobile liability insurance, the insurance company has the money!

And no liability insurance company will pay off on a willful tort—your deliberate act that harmed another. Look up Terry Graham v. Texas Farm Bureau. But they do have to pay off for negligence.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Cases in Point

Naysayers cry, “Show me a case where someone got convicted over a hair trigger!” OK, here you go:

Case One – New York v. Frank Magliato

This legally-armed citizen drew his Colt Detective Special and cocked the hammer when a raging junkie threatened him with a 24-inch police baton. Magliato flinched when the man lunged at him and unintentionally discharged a .38 Special bullet that killed the attacker. Long story short, he was charged with Murder.

His attorney had framed the defense as an accident. So, the judge forbade the jury to hear any testimony as to self-defense, since self-defense was reserved for intentional acts. He was convicted of Depraved Murder under the NY statute and spent years in prison.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The best his appellate lawyers could do was get the conviction reduced to Manslaughter. A majority of the appellate court found that pointing a hair-trigger gun was sufficiently negligent to warrant that charge.

Indeed, one dissenting justice wrote that Depraved Murder was correct! The single-action pull weight of the evidence weapon was found to be four pounds at the crime lab, and the jury was so informed.

Case Two – Crown v. Allen Gossett

A Montreal police officer unintentionally killed a suspect who turned on him when his S&W Model 10 .38 “just went off.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The defendant didn’t remember cocking the hammer. However, there were indications that it probably was in single-action mode at the time of the shot. After multiple trials, he was acquitted of Manslaughter.

Case Three – Michigan v. Charles Chase

A campus cop was arresting a dangerous felon who had disarmed and shot at a brother officer. He had his issue S&W Model 15 cocked in one hand and handcuffs in the other. When his left hand closed the last cuff, his right hand sympathetically tightened, triggering a fatal shot.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Manslaughter was the charge. The officer had been taught to cock the hammer “for a critical shot,” and training in “finger off trigger” had been lacking, resulting in acquittal. (The reasonable person doctrine: what would a reasonable person have done, in the same situation, knowing what the defendant knew? I think the jury forgave him because of his poor training.)

In those three cases, the death weapons had all been cocked to “hair-trigger” status. A light trigger pull can also give unscrupulous lawyers a hook to fabricate a false narrative of an unjustifiable accident.

Case Four – Florida v. Luis Alvarez

A suspect tried to pull a gun on two cops, and one of them shot him dead. The incident created a huge race riot—some believed a scapegoat was needed—and Officer Alvarez was charged with Manslaughter.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The prosecution concocted a theory that Alvarez had cocked his revolver and negligently discharged it. He was defended by two great lawyers, Roy Black and Mark Seiden – you can read about it in Roy’s book “Black’s Law.”

After an arduous trial that lasted eight or nine weeks, Alvarez was acquitted. Defense costs would have gone well into seven figures in today’s dollars.

If someone was tried under a “hair trigger negligence” theory and acquitted at trial, clueless Internet trolls would claim, “He was acquitted, so it doesn’t matter.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

They’ve apparently never gone through the ordeal of being tried for a serious crime. It’s like telling a cancer survivor, “You’re still alive, so cancer is nothing to worry about.”

I was a testifying or consulting expert in each of the above cases. You can see why I roll my eyes when the uninitiated and inexperienced claim, “It’s not a problem. It’s just a myth.” I was there. It’s not a myth. The hair trigger thing can most definitely be a problem.

Autoloading Pistols

Each of the above cases involved double-action revolvers. The same can happen with autoloaders:

Case Five – Santibanes v. Tomball

In this case, the suspect’s actions led to an inadvertent discharge of the officer’s GLOCK 21. The resulting headshot caused serious but non-fatal trauma. For this reason, the involved officer was cleared by the Grand Jury. However, a civil lawsuit alleged negligence for putting a 3.5/4.5-pound connector in his GLOCK.

GLOCK is adamant that one of their pistols, used for service or self-defense, has no less than a 5.5-pound pull. Between legal fees and settlement, the department paid out nearly half a million dollars.

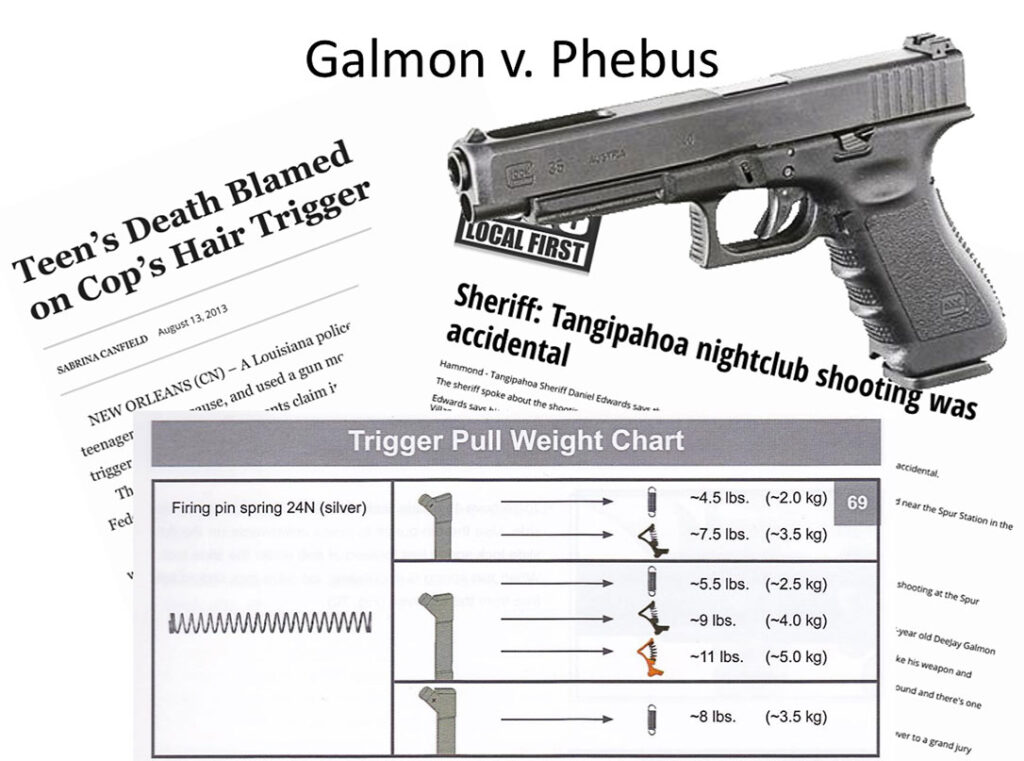

Case Six – Galmon v. Phebus

This case was an unintentional but victim-precipitated shooting with a GLOCK 35 that had been fitted with an aftermarket trigger. “Hair trigger” headlines may have panicked the officer’s department into settling for an amount that was never publicly disclosed. However, a member of that state’s crime lab, where the gun was examined, said later that the aftermarket trigger “added a zero to the amount of the settlement.”

So, How Light is Too Light?

It’s a matter of negligent adjustment of a machine—death or injury resulting. And one or both of two standards may be applied in court.

Manufacturer specification of pull weight is one standard. Specifically in this case “duty weight” meaning for a gun that is likely to be pointed at human beings while under great stress: an armed citizen’s defense gun or a cop’s duty weapon.

The other is common custom and practice. How have professionals who use that equipment daily historically made that adjustment on this particular machine?

For revolvers, there’s really no such thing as a “double action hair trigger,” but cocking the hammer makes it so. That’s why so many departments, from LAPD to NYPD, made their revolvers double-action only before the switch to auto pistols.

With 1911s, which have grip and thumb safeties, minimum duty pull weight seems to have settled around four pounds. Likewise, with striker-fired pistols, the 5.5 pounds of the standard GLOCK seems to have become something of an industry standard.