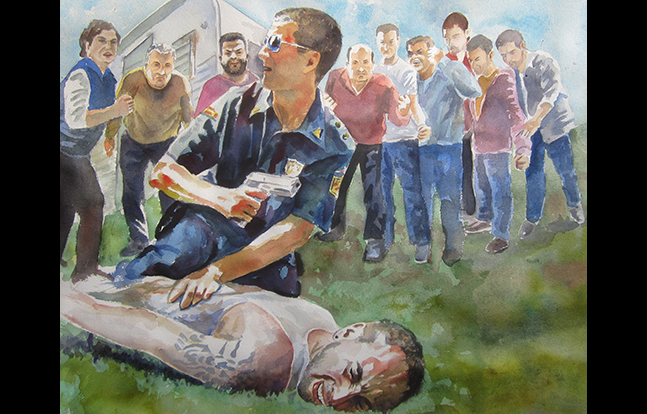

TRAILER PARK AMBUSH

As a rookie, you make mistakes. Most of the time, you learn from the mistakes and are a better officer for it. But when safety is on the line, mistakes can have deadly consequences.

Most officers can recount at least one time where they did something foolish that almost cost them a lot more than mere embarrassment. I made such a mistake when I was working for a small city police department in a large metropolitan area. On the evening in question, I had just been cleared from traffic court and had the unflappable confidence that only a first-year officer can seemingly muster.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I had just stopped by the dispatch center when a call about an armed subject came in. The location was well known to me: a mobile home in a rough little trailer park known for drug activity. The caller said her son, “Steve,” had threatened her with a pistol. Much like the neighborhood, I also knew Steve. He was an 18-year-old punk known for fighting and dealing dope.

The dispatcher taking the call said I was the only officer in service, so I turned and headed to my patrol car. A more experienced officer might have (correctly) surmised that the mother was not quite the victim she had portrayed herself to be, but in my youthful inexperience, I flew to the scene with lights and sirens running.

I quickly arrived on scene—without backup or a good grasp of the situation.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Although I thought I had parked an ample distance from the scene, the park residents all spotted my approach, so surprise was lost immediately. The complainant came running out of her residence shouting, “There he goes!” She was pointing at Steve, who was walking away from the area.

I shouted for Steve to stop, and, much to my surprise, he did. In fact, he turned around and started walking back to me. I thought, “This is great,” since I had expected a foot chase. What I didn’t expect was that he was coming back to fight.

As Steve approached me, I could see he did not have anything in his hands. What I should have also noticed was how he was clenching and unclenching his hands, plus showing other pre-attack indicators. As I went to handcuff Steve, the fight was on.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I was able to grab Steve’s left arm and put it into a weak arm bar, but I was not able to take him to the ground or otherwise fully control his movements. Steve twisted repeatedly, trying to grab my pistol. It was everything I could do to keep him from grabbing my pistol.

Somehow, I was able to pull out my pepper spray, but it had no obvious effect on Steve. Meanwhile, all of the local residents started to gather and shout. I was very aware that a bad situation was rapidly getting worse.

During the struggle, I tried to reach my portable radio to call for help. It was during this time that Steve broke free of my arm bar. He stumbled away a few feet and turned to fight some more. I saw him look directly at my holstered handgun, then lunge toward it.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I sprayed Steve again with the pepper spray, and the second application was effective. As Steve stopped and grabbed his face, I quickly took him to the ground and handcuffed him. However, the confrontation was not quite over.

My radio had come loose during the fight, so I was unable to communicate with dispatch. Now, with the suspect under my knee, a crowd of 20 or more was closing in around me. They were screaming to let Steve go and were threatening to harm me.

I drew my pistol and advised the crowd that I would shoot anyone who got any closer to me. Though they did not disperse, not a single person in the group dared test my resolve. Fortunately, I could hear sirens in the distance and knew help was on the way. The sight of my 6’2” lieutenant throwing people out of the way to get to me was the best thing I think I had ever seen in my life. I made a number of mistakes that night, but the lessons I learned kept me safe throughout the rest of my law enforcement career.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

—RJ, FL

HISTORY OF VIOLENCE

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Several months after being in an officer-involved shooting, I was working day-shift patrol when a young boy flagged me down. He frantically told me that his parents were physically fighting at his house down the street. I notified dispatch and requested backup as I responded. When I pulled up, I immediately recognized the residence—I was there the month before for a stabbing. It was an apartment building with three apartments situated side by side. The disturbance was in the first apartment on the west side of the building. I wasn’t certain if the same residents lived there since the area is transient. As I approached the building, several people were standing on the porch yelling for me to “hurry up” because the neighbors were fighting inside.

I entered the apartment and observed three subjects physically fighting in the middle of the living room to my left. I saw a smaller male and two larger females. I couldn’t determine the aggressor, so I drew my pepper spray, hoping to disperse them. I pointed the canister at the group and announced, “Police! Break it up!” The group separated. The male ran out the front door. One of the females backed up against a wall to my right. I perceived that she was trying to break up the other two, and she did not appear to be a threat. The other female ran toward the back of the house.

I didn’t know the layout of the house, but it wasn’t hard to figure it out once I heard the female rifling through the silverware drawer. For the second time in eight months, I found myself in a deadly-force situation. The last incident was still fresh in my memory, yet to be fully processed personally, professionally and emotionally. I began to contemplate my career decision, wondering what in the world I had signed up for. I had two-and-a-half years on the department and was already facing a second officer-involved shooting. I thought to myself that if I had to use deadly force, I would do so.

I drew my firearm. I really wasn’t certain if the female heard me yell, “Police!” She ran after I yelled it, yet having seen domestic drama in the past, I wondered if she was playing it up for my benefit. I really didn’t know if her intent was to harm me, so I pointed my firearm to the east, so that when she rounded the corner, I could shoot her if I had to. The problem: By that time, she’d be way too close to ensure I could walk away unscathed.

When the female rounded the corner, her eyes grew wide seeing the muzzle of my gun. She screamed and immediately dropped a large butcher knife, which she had over her head. She began to cry and stated she was unaware of my presence. She said she was tired of being abused. I placed her into custody, charging her with aggravated domestic battery and aggravated assault.

Fifteen years later, I still remember this female’s name. So, several years later, when I responded to a shooting in a housing development, I recognized her as that female. This time she was the victim. Her boyfriend, the same male, shot her. My partner and I were placed on guard duty at the hospital when he called the hospital looking for her, determined to finish the job. When the case went to court, I was subpoenaed by the defense. Generally, I despise testifying for the defense, but I had no reservations about sharing my knowledge of the mutual violence between these two. I do not know the outcome of this case, but several years later, my path once again crossed with her.

Two years ago, while working a traffic detail in a high-crime area, I stopped a vehicle for an equipment violation. I approached the driver and asked her for her driver’s license and insurance. I verified her identity and realized she was the knife-wielding female from 15 years before. I asked her if she remembered me. She looked puzzled. I reminded her of our last two encounters. She looked at me nervously, unsure where I was going with the conversation. I told her I wasn’t giving her a ticket, and out of genuine concern and curiosity, I asked her if her personal situation improved. She told me that she was no longer in that violent situation. As I concluded the stop, I smiled at her and said, “By the way, you’re welcome.”

She responded, “Oh yes, thank you for not writing me a ticket.”

I told her, “That’s not what I meant, but you’re welcome for that, too.” —SA, IL