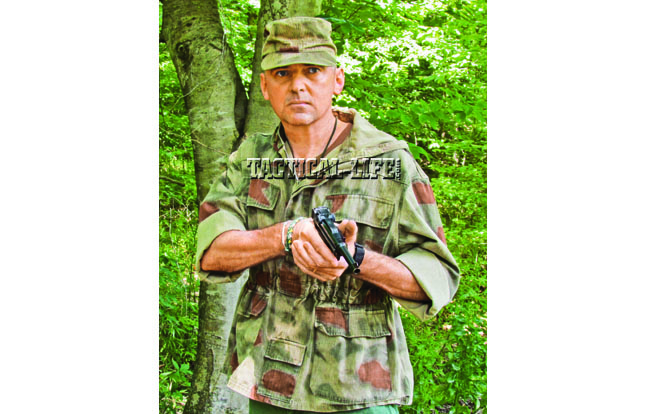

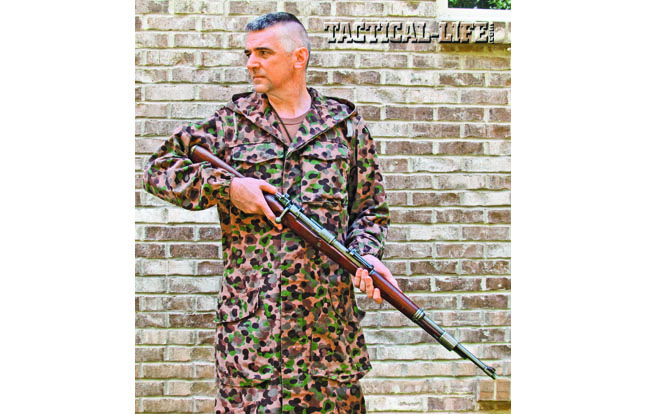

The earliest combat uniforms were little more than rudimentary IFF (identification friend or foe) systems—one color meant good guys, while another color meant bad guys. Shoot the bad guys; don’t shoot the good guys. It was about that simple. Over time, uniforms retained their distinctive colors but became more functional. Wool was still the industry standard, but soldiering is a stuff-intensive undertaking, and having plenty of pockets is a plus. World War II saw the first realistic employment of camouflage uniforms and, as with most things both groundbreaking and military, the Germans paved the way.

When I first got into this gig, we were still wearing OG107 jungle fatigues. Dyed a timeless olive drab, these fatigues sported four bellows pockets on the blouse as well as side cargo pockets on the trousers. Construction was a rip-stop, 100 percent cotton poplin that, once broken in, felt like the next best thing to being naked. As the Army bureaucracy has always seemed to suffer from a chronic comfort allergy, these fatigues had to be starched in garrison. I logged many an hour sweating over an iron with my classic jungles starching and pressing until my trousers could be used to bludgeon somebody to death. The dark, homogenous color looked cool but in practical usage was fairly easy to pick out in the woods. We could do better.

Battle Dress

In the early ’80s, we developed the Battle Dress Utility (BDU) uniform. It sported a Woodland camouflage pattern that was itself spawned by the ERDL (U.S. Army Engineering Research and Development Laboratory) camouflage pattern from the 1960s. It possessed a rumored innate resistance to IR transmissivity that was said to offer some modicum of camouflage against FLIR sensors. As a result, BDUs were not supposed to be starched so as to preserve this mystical quality.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The shirt design was a variation on the four bellows pockets of the OG107’s, and the pants sported the same cargo pockets. About two minutes after the first battalion sergeant major saw those floppy bellows pockets flapping in the breeze, we all starched them. (We would rather face Communist Bloc snipers with FLIR than the wrath of a command sergeant major in garrison.) The BDU design was a decent uniform. It still prioritized appearance over function, and patches had to be laboriously sewed on, but it was a step in the right direction. One of the major problems with both of these uniforms was that their cotton content allowed them to burn vigorously.

Meanwhile we aviators were humming our own tune. The classic CWU-27/P flyer’s coveralls sported logical pockets aplenty and, even better, were constructed of an artificial Aramid fiber called Nomex, which was innately flame-resistant. Long, handy zippers let us step into and out of them readily, and the cut and design simply dripped cool functionality. Special operations personnel enjoyed our aviator’s coveralls as well, the flame-resistant characteristics being a great boon in the CQB environment. SEALs doing VBSS (visit, board, search and seizure) ops wore them as a matter of course.

Army Combat Uniform

Two wars later, we found ourselves focused on the desert for a while and giving the jungles a pass. Designed at astronomical cost soon after 9/11 (it was rumored to have cost $5 billion), the new Army Combat Uniform (ACU) sported a digital Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP) that was supposed to work in all environments, including snow, sand and everything in between. As with all glorious compromises, the ACU did not work really well anywhere, but the design was a great step forward. The ACU shirt sports a Mandarin collar worn down in garrison and up when underneath the Improved Outer Tactical Vest (IOTV) body armor. Arm insignia and nametapes are secured via Velcro, and there are pouches for elbow pads. The arms are festooned with pockets, and the front is secured with a fairly heavy zipper. This intermediate step led to today’s state of the art.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

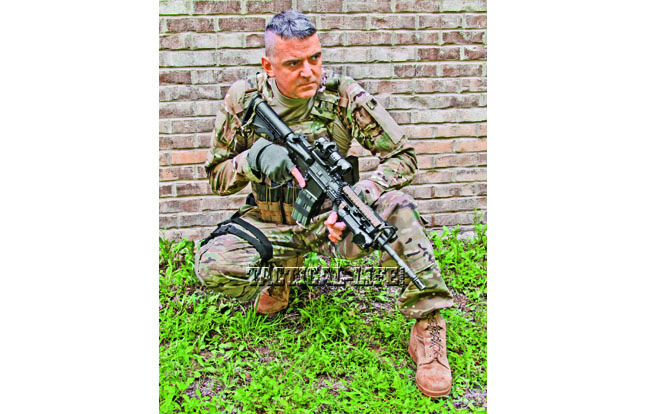

The newest Army Combat Shirt (ACS) is a simply outstanding piece of kit. Sporting the same sort of wicking, body-hugging technology that made Under Armour a household name, the ACS breathes such that operators in hot environments wearing the now ubiquitous body armor are as comfortable as possible. The arms of the shirt are made from heavier stuff and incorporate bilateral versions of the beloved arm pockets from the old flyer’s coveralls as well as built-in elbow pads. There are pen pockets on the left forearm as well. The shoulders incorporate small square IR glint pads that are covered by Velcro covers when in garrison. When uncovered, they shine brightly under IR light such that imagers on platforms like AC-130 Spectre gunships and AH-64 Apache attack helicopters can more readily determine friend from foe.

Pants are not quite so revolutionary but still incorporate a second pair of pockets on the bottom of the legs. The classic cargo pockets now include bungee cords to snug them flush when stuffed with gear. The traditional button fly has always been tough to manipulate with gloves (I served in Alaska—it is a big deal at 45 below zero), but unlike a zipper, it is pretty tough to tear up. The newest combat trousers include pouches for kneepads that can be game-changers when you have to stop and drop on rocks and concrete. Conventional kneepads inevitably seem to end up around my ankles when I really start moving around. The pant legs blouse over the tops of combat boots in the classic fashion. All of the modern uniform components are both breathable and flame-resistant. They are also instilled with Permethrin insect-repellent to help keep the creepy crawlies at bay. Additionally, they are designed to wick moisture away from the body to facilitate employment in the hell-hot places within which today’s American warriors seem to be perpetually operating.

MultiCam

The science behind the new MultiCam camouflage pattern is 21st century cool. Bearing an esoteric similarity to the German Waffen SS Autumn patterns from WWII, the MultiCam pattern designed by Crye Precision in conjunction with Natick Labs really is remarkably effective in a variety of environments. In an Army simply drunk with acronyms, the newest iteration is called OCP for Operation Enduring Freedom Camouflage Pattern. OCP is comprised of seven different colors and has been around since the turn of the century. MultiCam was actually a competitor in the 2002 trials to select the ACU replacement for the BDU uniform, but lost out to the grey-predominant Universal Camouflage Pattern then falsely thought to be the best for everybody in every environment.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Nature is chaotic. Solid colors, even if they are dull and organic, stand out against a naturally cluttered background. The MultiCam pattern does a near-supernatural job at breaking up outlines and dissolving into dun-tinted landscapes in both wooded scrub and urban filth. As a result, MultiCam is remarkably effective in deep woodland as well as brown desert. The science behind contemporary American digital patterns was actually birthed in Canada in the 1980s and involves detailed scientific assessment of the mathematic fractals found in nature as well as the physiology behind the way the human brain processes shapes and colors. There is an ongoing trial to replace the UCP and OCP camouflage with a next-generation pixilated pattern rumored to be planned in three different hues: Woodland, Arid (Desert) and Transitional Areas of Operation. The new system will also incorporate a melding of the three to be used on universal field gear like plate carriers, pouches and NBC suits.

Today & Tomorrow

The Big Green Machine has undergone a remarkable transformation in the past 30 years. When I first started out, you might leave a smoking hole, but so long as your boots were polished and everybody looked the same, the boss was happy. Nowadays, individualized, cool-guy stuff dangles from everybody’s weapons. Entire closet industries thrive around the market for optimized ninja gear to make going to war more effective and comfortable. Just as the 1960s-era space program eventually brought us freeze-dried food, cellphones, GPS and Velcro, this contemporary technology spills over into both the law enforcement and civilian markets.

It has been a few years since I had some grizzled first sergeant who earned his spurs in the Ia Drang scream at me because he couldn’t see his reflection in my jump boots or perceived more than a 5 o’clock shadow on the back of my head. As I look with pride at the hard, young studs who willingly stride forth to close with and kill the enemies of my country today, I am warmed to see that their uniforms and gear are purpose-designed to help them pull their missions and get home safely. It is human nature to wax nostalgic for the good old days. In this case, I think these youngsters do it markedly better than we did.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below