During World War II, the M1 Garand rifle proved its mettle on countless battlefields around the globe and was universally recognized as the premier general-issue service rifle of the war. Springfield Armory and Winchester manufactured over 4 million M1 rifles by 1945, and it was generally assumed that there would be an adequate supply of Garands to equip the post-war American military. However, this assumption was proven wrong when the North Koreans invaded South Korea in 1950.

The pared-down American armed forces were ill prepared for another war. Obviously, one of the key weapons needed was the battle-proven M1 rifle. The Garands left over from WWII were refurbished and issued to troops deploying to Korea, but it was feared that existing supplies would be insufficient to meet the unexpected demand. Springfield Armory was ordered to get new M1 rifles back into production as soon as possible, but the lag time required to obtain the necessary machinery and manpower to accomplish this task proved more difficult than expected. The only viable solution was to acquire the additional rifles from civilian manufacturers. This was certainly not without precedent, as commercial manufacturers had supplied weaponry to the U.S. military almost from the founding of the republic.

New Supplier

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In order to augment Springfield Armory’s production, two civilian firms were selected to manufacture the new M1 rifles: the International Harvester Company (IHC) and Harrington & Richardson.

On June 15, 1951, a contract was granted to IHC for 100,000 M1 Garand rifles to be manufactured at the firm’s Evansville, Indiana, plant, with production to start by December of 1952. The Evansville plant was constructed during WWII by the Republic Aviation Corporation to manufacture P-47 Thunderbolt fighter aircraft. After the war, the plant was purchased by IHC for manufacturing various types of commercial products, including air conditioners, refrigeration units and farming equipment.

- RELATED STORY: Viet Cong Weaponry – 14 Small Arms From the Vietnam War

At first glance, IHC would seem to be a rather odd selection for manufacturing military service rifles since the company had absolutely no prior experience in the production of firearms. Interestingly, one of the primary reasons for choosing IHC was the plant’s geographic location. It must be remembered that by the early 1950s, the looming threat of nuclear war with the Soviet Union was uppermost in the minds of our military planners. The dispersion of vital military production facilities was deemed a very important consideration.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

During WWII, the only two manufacturers of M1 rifles were Springfield Armory and Winchester, which were only about 60 miles apart. This was not viewed as a problem in the 1940s. However, by the early 1950s, it was recognized that a nuclear strike on the Eastern Seaboard could deal a crippling blow to the nation’s arms production.

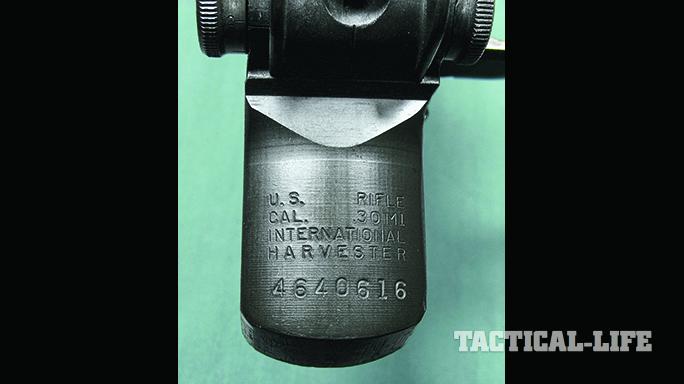

In addition to IHC’s M1 rifle production, Harrington & Richardson was subsequently granted a contract on April 3, 1952, for the manufacture of 100,000 Garand rifles with additional contracts to follow. IHC was assigned two separate blocks of serial numbers for M1 rifle production: 4,400,000 to 4,660,000 and 5,000,501 to 5,278,245.

Early Issues

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As IHC began plans for production of the M1 Garand, a number of formidable problems became apparent. The firm’s lack of experience in manufacturing firearms made the problems worse. In hindsight, it is obvious that IHC was ill prepared for the new challenge. The company’s management naively believed it could make the Garand rifles using its existing manufacturing equipment without the expenses and delays of acquiring specialized firearm gun-making machinery. This naivety was further evidenced in the company’s grossly optimistic goal of delivering the first rifles by Christmas of 1952.

With the exception of the receiver, the barrel was the most complicated component to manufacture. It was decided to subcontract the production of IHC’s M1 Garand rifle barrels to the Line Material Company based out of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. This company was a well-regarded maker of various equipment items used in the transmission of electrical and telephone lines. Line Material’s foray in making M1 rifle barrels was not limited to IHC, as the company also made large numbers of barrels for use in rebuilding Garand rifles at several ordnance facilities. The barrels made by the company were of of the highest quality thanks to exacting standards.

- RELATED STORY: Remington Model 10 Shotgun – The Other Trench Fighter

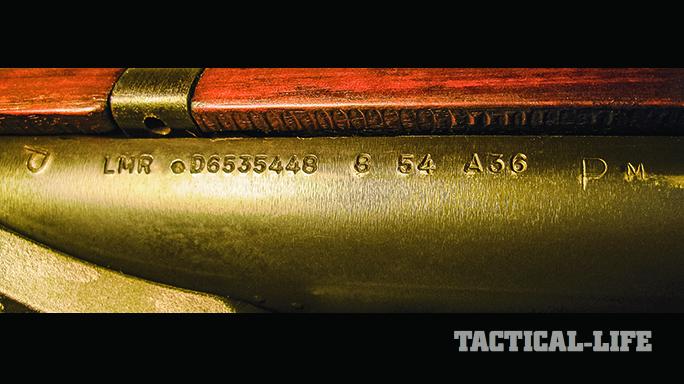

The barrels made by Line Material can be identified by the “LMR” marking on the right side, stamped next to the drawing number (D653448), month and year of production, heat lot identification, “P” (proof) and “M” (magnetic particle inspection). Except for very early examples, the barrels made under subcontract for IHC can be identified by a punch mark between the “LMR” and the drawing number.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Unfortunately for IHC, the availability of the excellent LMR barrels was one of few things that went right during the startup of Garand production. As the myriad problems faced by the fledgling arms-maker surfaced, John Stimson—John Garand’s chief tool-and-die maker—was sent to the Evansville plant to help rectify the production woes. As production slowly got underway, serious functioning issues arose, with the most vexing being a tendency for the rifle to badly jam. This problem resulted in the assembly line being shut down for three months. Eventually, engineers discovered that the jamming issue was caused by flawed spring tension setting specifications.

Receiver Sources

Although IHC made most of the receivers used in its M1 rifles, the firm did acquire a number of receivers from Springfield Armory and Harrington & Richardson. Eventually, there were four distinct variations of M1 receivers manufactured by Springfield Armory and H&R for International Harvester. These are in addition to the receivers made by IHC.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

SA/IHC “Arrowhead”: The first receivers made by Springfield Armory for IHC were in the 4,440,000 to 4,441,100 serial-number range. The logo markings on the receiver were applied by Springfield Armory, and serial numbers were stamped at the IHC plant. Most were fitted with LMR barrels. These receivers have been nicknamed “Arrowheads” by collectors because the configuration of the nomenclature markings vaguely resembles an arrowhead with a broken tip.

SA/IHC “Postage Stamp”: The second variant of M1 Garand receivers supplied by Springfield Armory with the nomenclature marking consisting of four even lines stamped on the receiver. Collectors have dubbed these the “Postage Stamp” type. The majority of these rifles were assembled with LMR barrels (generally dated late 1952 or early 1953).

- RELATED STORY: World War I Excellence – Air Service M1903 Rifle

SA/IHC 4.6 Million “Gap Letter”: The third variation of M1 receiver acquired by IHC from Springfield Armory was the so-called “Gap Letter” type, which had a noticeable space between the centers of the first two lines of the nomenclature logo. The reason for this change in the marking format is not known.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

SA/IHC 5 Million “Gap Letter”: The final variant of receiver made by Springfield Armory for IHC to fulfill the latter’s production commitments was the “Gap Letter” variety. These receivers were serially numbered in the assigned range 5,198,034 to 5,213,034, and consisted of about 15,000 units.

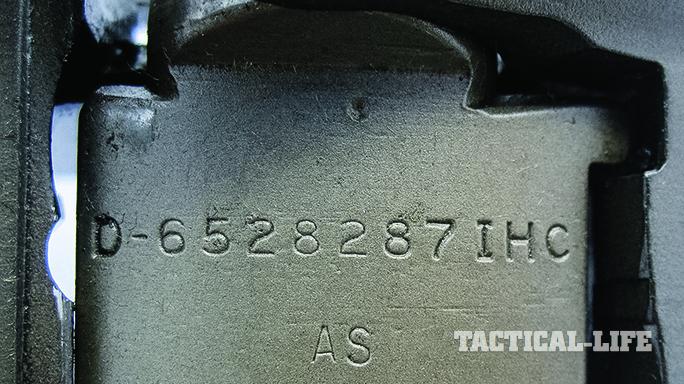

H&R/IHC Receivers: Near the end of IHC’s production run, the company needed additional receivers to complete its production commitments. To this end, a relatively small quantity of M1 Garand receivers (approximately 4,000) was supplied to IHC by Harrington & Richardson. These fall into the 5,213,034 to 5,217,065 serial-number range. It is interesting to note that the logo nomenclature on these receivers appears to have been stamped by IHC (with a “Postage Stamp” profile), although the serial numbers and the drawing numbers on the receiver leg were applied by Harrington & Richardson.

In-House Progress

Although Springfield Armory and Harrington & Richardson supplied IHC with a number of receivers, the vast majority of the company’s M1 receivers were made in-house. All of these were of the “Postage Stamp” variety. The receiver drawing number marked on the right side of the receiver leg was initially “IHC D6528291,” which was later changed to “D6528291” without the “IHC” prefix.

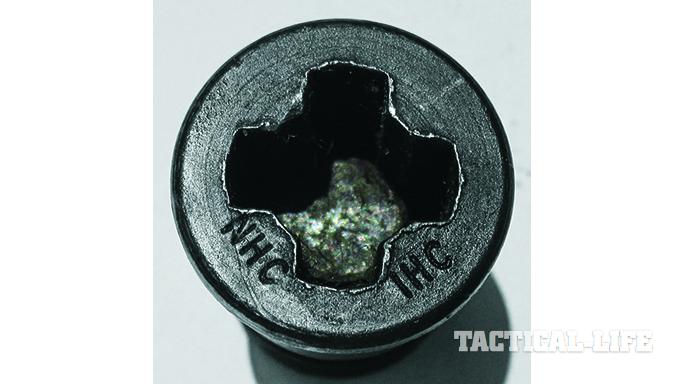

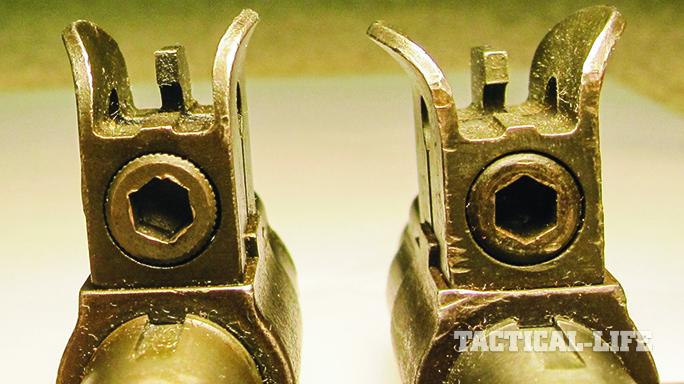

The primary components, including the bolt, operating rod, trigger housing, hammer, gas cylinder lock screw and rear sight’s windage and elevation knobs, were generally marked “IHC” along with the appropriate drawing number and/or subcontractor initials. Although they weren’t marked, most of the IHC front sights had a noticeably wider space between the two flared protective “ears”—approximately 0.875 inches across, as compared to the other manufacturers.

- RELATED STORY: Winter War Fighter – The Mosin-Nagant M/28-30

Although it was originally planned for IHC to manufacture the rifle stocks and handguards in-house, it was determined that these components should be made by subcontractors, mainly the S.E. Overton Company. Interestingly, IHC stocks had numbers (normally four digits) stamped in the barrel channel. These numbers are believed to represent a variation of the Julian dating system. No other manufacturer utilized such numbers. Another feature of the IHC stocks was the narrower profile behind the receiver heel as compared to the H&R stocks. There were several variants of stock inspection stamps used, including a “crossed cannon” escutcheon, but by late 1953, the familiar 0.5-inch Defense Acceptance Stamp came into use.

Eventually, IHC accepted production contracts totaling 418,443 M1 rifles. Unfortunately for the company, IHC’s parent company sold the Evansville property to the Whirlpool Corporation in September 1955. To make matters worse, the contract called for Whirlpool to take possession of the plant just four months later. Although IHC had manufactured slightly over 300,000 rifles by this time, it would have been impossible for the firm to build the remaining 100,000 in such a short period. This resulted in the company having to negotiate an early termination of the final contract. Despite the trials and tribulations encountered, IHC eventually manufactured over 337,000 M1 rifles by the time it ceased production in December 1955.

Scattered Surplus

Prior to the late 1970s, IHC M1s were rather hard to find on the domestic civilian market as compared to those made by other manufacturers. In the late 1950s and into the 1960s, many late-production Garands, especially those from Springfield Armory and IHC, were shipped to various allied countries. While some H&R Garands were also shipped to some overseas allies, most of these rifles were from IHC.

- RELATED STORY: Trench Warrior – The Pedersen Device

Once the rifles were supplied to foreign governments, they could not be “re-imported” back into the United States for sale on the civilian market. Between 1977 and 1978, a loophole in the regulations permitted some of these former military rifles to be brought back to the U.S., but sales were restricted to full-time law enforcement officers. Quite a few rifles changed hands in this manner, and in just a few years, IHC-made M1 Garands became a bit easier to find. The regulations were eventually tightened up to prohibit such sales. However, a few years later, the Director of Civilian Marksmanship and its successor, the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP), acquired fair numbers of Garands, including some IHC models, from overseas and these were sold on the civilian market to qualified buyers.

The CMP periodically has IHC Garands available for sale. They are among the bestselling guns sold by the CMP and are highly sought after by collectors due to the interesting receiver variations and the smaller number of rifles made as compared to those manufactured by Springfield Armory. The story of the International Harvester Garand is yet another example of how America’s civilian manufacturers assisted the nation when called upon to make badly needed weaponry.

This article was originally published in ‘Military Surplus’ #188. For information on how to subscribe, please email subscriptions@