To be good at any manual skill or sport, you must practice.

One reason shooting is a superior sport is because you can train and practice at home for no cost without ammunition. Dry-fire practice is the act of shooting and gunhandling without live ammunition. Unfortunately, and for no good reason, too many gun owners treat dry practice like the weather–something everyone discusses but few do anything about. Most authors discussing technique conclude with a dubious tip like, “You need to practice to become good.” Some recommend dry firing for a few minutes a day. This is all true but it’s just lip service to the true importance and effectiveness of dry practice. Instead of just talking about it, let’s find out how important such practice is. How much improvement can you realistically expect to make with 15 minutes per day?

To answer this question, I set up some experiments. My brother, Jason, and I were back home for a period. He was in the area for a while, so I asked if he’d like to do a little shooting with me. Jason had been a semi-active shooter for one summer, which culminated in participating at a local Steel Challenge-type match with me. However, he hadn’t shot for years since, having taken up golf instead (ugh!). Jason was interested but mentioned he didn’t have much spare time. An experiment was born. Given a moderate amount of dry practice, how much improvement can we expect to see?

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Practice Routine

To establish a baseline, I needed to know his “before” skills. After checking for safe gun handling through dry fire, we shot the following drills: Slow-fire group of six rounds at 25 yards, while standing with a two-hand hold; 12-inch plate at 10 yards, timed from ready; and 12-inch plate at 10 yards, timed draw.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

RELATED: 4-Point Training for Rock Solid Plinking

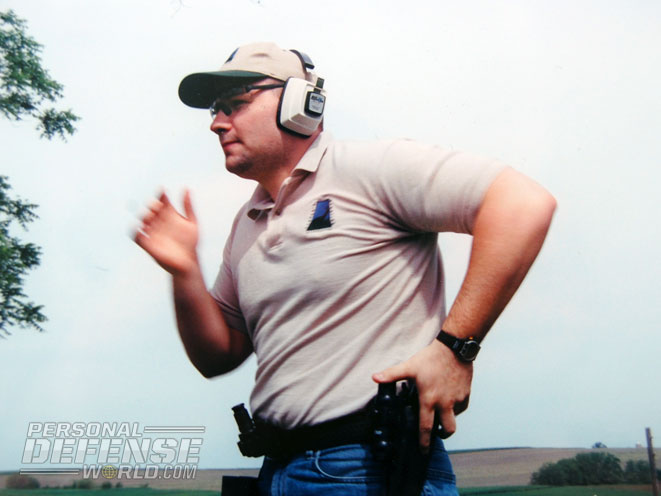

At the first session, Jason’s slow-fire groups averaged 9 inches. His timed shots from ready averaged 1.55 seconds and 2.6 seconds from the holster for reliable hits. The speed drills were timed with an electronic shooting timer on an unanticipated signal, and everything was recorded on video. The draws were from the “surrender” position (wrists above shoulders), and all shots, including slow-fire groups, were fired double action.

For the record, Jason had previously shot for just one summer and hadn’t touched a gun for several years since. Saying he felt “rusty” is an understatement, even though his performance was better than plenty of police officers and military personnel I’ve shot with. In addition, this was Jason’s first exposure to using a scope sight, having bought and mounted it on a whim but never practicing with it. That slowed him down. Technology can help only if you use it efficiently!

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The shooting problems displayed were classic novice errors. He had a tendency to blink his eyes on discharge, to lose the dot while presenting towards the target and to dip or “scrunch” his head on the draw. Also, due to inexperience and a long layoff, Jason was uncomfortable “stacking” the double action, so he waited until the gun stopped before starting the long trigger pull on timed shots. This caused a long delay before the shot broke.

RELATED: 10 Tips to Improve Your Shooting at the Range

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After the live session, we reviewed the video, discussed the results and made a plan for improvement. The most vital part of any practice routine is a written schedule. Over the course of two months, Jason worked on basic marksmanship with a little gun handling. His routine was: 25 slow-fire shots without a target, arms rested across a table to focus on grip and trigger control; 25 slow-fire shots without a target, standing to work on stance and trigger control; and 25 presentations and shots from ready to target, untimed.

For his convenience, Jason took broke this into three separate five-minute sessions and took about 15 minutes per day total. He found a place he could practice without interruption every day. The aiming point for presentations was a 1-inch square taped to a bulletproof wall in his practice place. At 3 feet away, this roughly simulates a 10-inch target at 10 yards. Jason found breaking this up into small, quick sessions helped maintain his focus.

Improvements

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After about two months, we headed out for a live-fire session. His good results were becoming monotonous. Grouping accuracy at 25 yards improved, now averaging 5 inches at 25 yards. Presentations from ready were consistently 1-second flat, with some good ones in the low 0.9s, yielding a 10-percent improvement.

RELATED: Massad Ayoob’s Speed and Accuracy Shooting Drills

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

This improvement occurred for a number of reasons. The first, and most important, is that the shooter was willing to put in regular, scheduled, disciplined practice. It was only a few minutes a day, but Jason actually did it, everyday, instead of just talking about it, and followed through with his usual high work ethic. If he cheated anything, it would have been doing a little more practice than reported. Most gun owners have the opposite problem. Working as a firearms instructor, the most difficult task is getting people to do the work.

If this level of progress seems high, consider he fired 5,900 “shots” in two months (2,100 and 3,780, respectively) not counting actual live fire. More importantly, Jason didn’t mindlessly click the gun or slop through the gun handling. His shots were deliberate, and he often jotted down a few notes after each session. Sometimes the daily journal entry was a single line in the notebook, but he took the time to evaluate and write down something every day. Sessions were deliberately kept short so a high level of focus could be maintained.