You’ve heard it before—don’t drop the slide on an empty chamber, don’t snap the cylinder closed on a revolver. For some, this has been gospel since the first time they held a firearm. For others, it’s superstition, or maybe just old-school fuddlore passed down from someone who “used to be a cop.” But when you’re in the business of fixing broken guns, or making sure they don’t break, you start to develop a sense of what’s actually going on.

Snapping Revolvers and Slamming Slides: Myth and Fact

I’ve had a front-row seat to this argument for years, both in person and online. Likewise, I’ve watched people get into heated arguments over it. I’ve even seen YouTube videos that make fun of both camps. And I already know that when this article drops, somebody’s going to send me hate mail with the subject line “You’re Dead Wrong.” That’s fine.

However, before you die on your hill, let’s look at what’s actually happening when people do these things. Not to mention what it can cost them.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Slamming Slides: The Mechanics

Let’s start with slide drops. What people are talking about here is hitting the slide release on an autoloading pistol when the gun is empty. No mag in, no round chambered. The slide rockets forward, slamming into battery with nothing there to send into the chamber.

Now, all myths come from some kernel of truth. I can imagine a guy somewhere who dropped his slide, found a crack in the frame a few moments later, and made the connection. But just because he believes it doesn’t make it true in every case. Whether it’s a problem depends entirely on what kind of gun you’re dealing with.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

So, to keep this focused, let’s split them into two families: Metal-framed cross-pin style pistols and Polymer-framed striker-fired pistols.

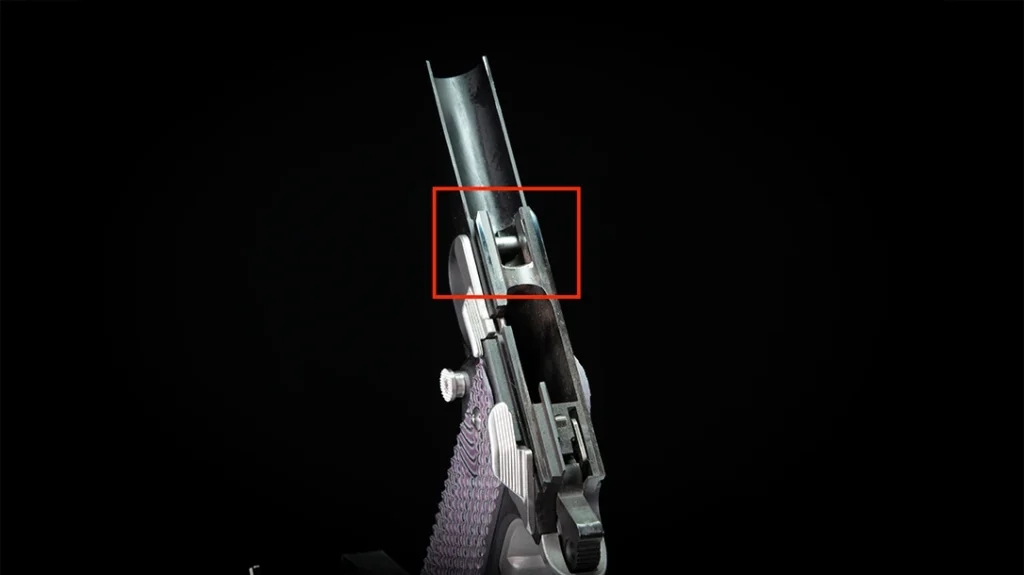

Cross-Pin Pistols

A cross-pin pistol is something like a 1911, CZ-75, Browning Hi-Power, or Beretta 92. All of these use a transverse pin or slide stop that passes through the frame and often supports the barrel. Sometimes by way of a swinging link, like in the 1911. In these systems, the pin is under some direct stress when the slide slams forward.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Snapping the slide once probably won’t hurt anything. But snapping it every day over time can start to peen that pin or oval out the holes it rides in.

On a 1911, especially, you might start to see premature wear in areas that weren’t meant to be load-bearing in that way. Eventually, that damage spreads. I’ve seen peened frames, cracked locking lugs, and loose lockups; all from repeated “dry slamming” of a 1911.

Now here’s the catch: sometimes shooters justify this behavior by saying, “Well, I need to chamber a round in my carry gun.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

And sure, that’s legit. But even that has its limits. If you regularly load your .45 ACP EDC by letting the slide slam home on a chambered round off the mag, you’ll start to see the bullet crush its crimp. This is where the bullet gets pushed deeper into the case.

That reduces case volume, which can increase pressure, sometimes to unsafe levels. (Again, this needs to be the same cartridge multiple times.) It’s called a compressed load, and while you may never blow up your gun, you’re walking an unnecessary tightrope.

As a rule, when running a cross-pin gun, drop the slide only when you’re feeding a round off a magazine. Otherwise, ease it forward and respect the mechanical design.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

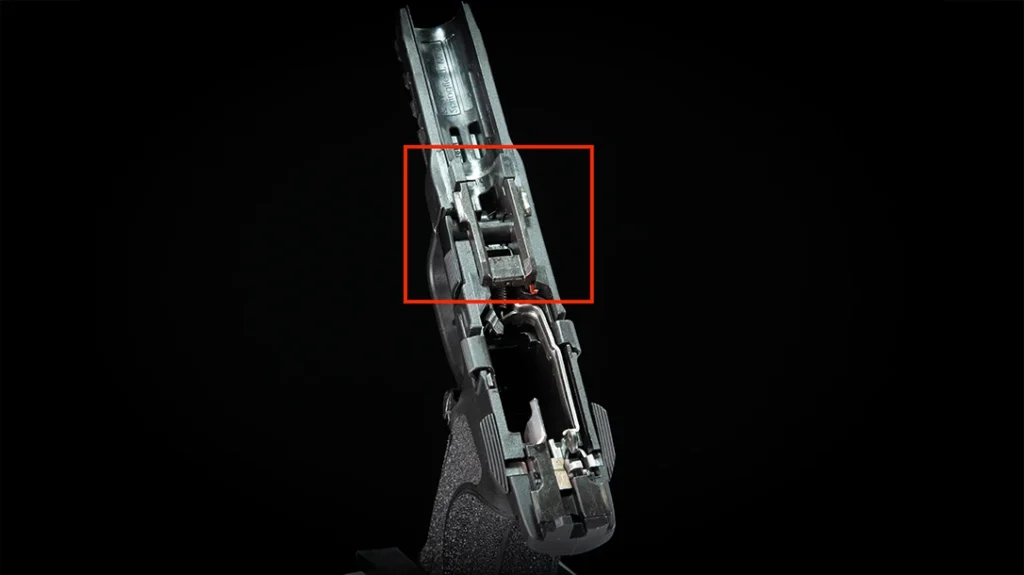

Striker-Fired Guns Are Different

Polymer-framed striker guns like Glocks, Sig P320s, CZ P-10s, and the like are much more forgiving. These guns are built to survive a different kind of abuse. Their parts don’t rely on fragile barrel links or cross pins to manage slide velocity.

When I dry-fire students in a class, we snap the slides all day. It’s part of how we train trigger resets, tap-rack drills, and malfunction clearances. These guns don’t care. They were born for it. Could something break eventually? Sure, everything has a limit. But the common striker-fired platforms take this kind of use incredibly well.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Still, I treat all metal-framed, cross-pin pistols like they need a little extra gentleness. They’re not less durable, but they’re just built around different assumptions.

Movie Cool, Mechanical Nightmare

Now let’s talk about revolvers.

We all know the sound: that zipp followed by a clack as a revolver cylinder spins shut. It’s the sound of an action hero making a point. That moment is baked into pop culture, old movies, TV shows, and radio plays. Somewhere along the line, that slick one-handed spin became part of gun culture.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But that doesn’t mean it’s good for your gun.

Revolvers Are Not the Same

When you snap a cylinder shut, what you’re doing is forcing a rotating, precision-fit piece of metal into a detent by inertia. Every time that cylinder slams home, something has to absorb the shock. And depending on your revolver’s action, different parts are taking the hit.

Let’s look at Smith & Wesson double actions and Colt double actions. We’ll include Ruger as well, since Ruger’s GP100 and SP101 series are extremely popular and mechanically distinct.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Smiths use a small frame-mounted pin at the rear of the cylinder to lock it into battery. Most modern S&W revolvers also include a secondary detent at the front of the ejector rod. This gives the gun a more robust lockup and helps it resist wear over time. Still, that rear pin is a wear point, and slamming the cylinder causes that hole in the yoke to gradually wallow out.

Colts, particularly the older models like the Python and Trooper series, rely on a larger cross pin that locks the cylinder in place. They don’t use a front detent, and the tolerance is usually tighter. A slammed cylinder on a Colt can cause visible frame wear faster than on a Smith.

Ruger revolvers, especially the GP100, are built like tanks. Their cylinder lockup is extremely solid and designed to take a beating, but even then, snapping them shut repeatedly is still a bad habit. The more you do it, the more you accelerate wear to the yoke, detents, and alignment geometry.

Misdiagnosing the Damage

The most common long-term issue I’ve seen from cylinder snapping is a loose lockup and bore misalignment. This leads to something called lead shaving, where the bullet gets slightly clipped as it transitions from the cylinder into the forcing cone. A lot of shooters mistake this for a timing issue.

But it’s not always timing; it’s indexing. The cylinder is rotating into the right position, but it’s not staying centered because the detents are loose or peened.

And here’s the worst part: it’s not easy to fix. You can’t just swap in a new part. Once the yoke or frame hole is ovalized, the only real solution is to weld it closed and remachine it. That’s not what I would call a quick job.

So, One Slam Ruins a Gun?

No. This isn’t about scolding someone for a single mistake. It’s about behavior over time.

Can you get away with snapping your 1911 slide every now and then? Probably. Can your Ruger GP100 survive a few snapped cylinders? Definitely. However, habits become behaviors. And behaviors have mechanical consequences.

I’ve had students show up to class with revolvers that wouldn’t lock up correctly or semis that had excess wear in the frame rails. In almost every case, it wasn’t a defective gun; it was a worn gun. And they had no idea they were the ones wearing it out.

Ugly Things to Do

Here’s the part where I say the quiet thing out loud.

Even if your gun could take it, why would you treat it that way?

You can call me a curmudgeon, but I don’t let students snap cylinders shut. I’ll correct it every time. Not because I’m mad, but because I understand the process to fix those guns.

So, if you want to keep snapping every slide and slamming cylinders, fine. Do it to your own gun. Just don’t do it to mine.

And I’ll leave you with one of my favorite quotes from Mark Novak, a world-class gunsmith and absolute gentleman:

“It’s just an ugly thing to do to a gun.” – Mark Novak

Shoot safe.