British “Enfield” rifles are some of the most iconic small arms in the world. Having served around the world, they are the symbol of British power. The No. 1 Mark III Lee-Enfield rifle is, without a doubt, one of the most widely recognized of these. Its reputation for ruggedness and reliability are legendary, while its smoothly operating bolt and 10-round, charger-loaded magazine gave the British “Tommy” a significant firepower advantage over his adversaries at the turn of the 20th century.

- RELATED STORY: The Best Wartime Firearms That Appeared in Movies

Only two complaints worth heeding had arisen about the No. 1 during World War I: the rear sight and the thin barrel. Experience with the American-made P14 Enfield rifle had shown that an aperture rear sight would be more practical and easier to use while making the barrel heavier, and modifying the stock to allow the barrel to be free-floating would improve accuracy.

Arsenal Upgrade

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Work on a new rifle began at the Enfield arsenal in 1922, and by 1924 approximately 20,000 No. 1 rifles had been modified for troop trials. These experimental No. 1 Mk V rifles had the same general appearance as the Mk III except for a receiver-mounted aperture rear sight, which was adjustable from 200 to 1,400 yards, and an additional, fitted barrel band.

Further development was deemed necessary, and between 1929 and 1935 another rifle, the No. 1 Mk VI, was produced for extended field trials. The receiver was completely redesigned to ease production, but at the same time a better grade of steel was utilized to increase its strength. While the No. 3’s receiver had a nicely rounded profile, that of the Mk VI was all flat surfaces and right angles. The bolt and magazine were modified so that they were not interchangeable with those of the No. 1; instead, a new bolt catch was used and the charger guides were integral with the receiver. That 19th century anachronism, the magazine cutoff, was discarded and a number of stamped parts replaced those previously forged.

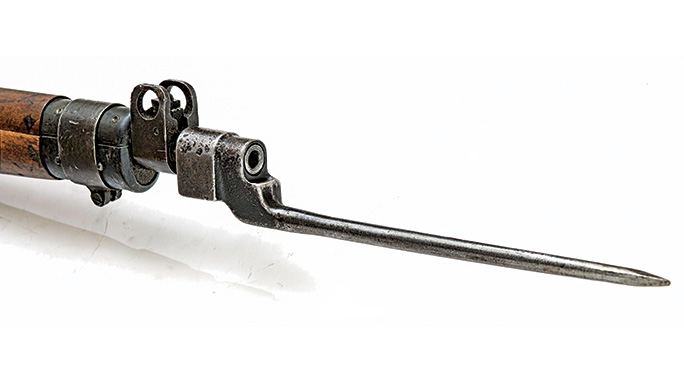

In November of 1939, the improved Rifle No. 4 Mk I officially replaced the long-serving No. 1 as the standard rifle of the British Army. The No. 4’s most distinctive feature, apart from the traditional Lee-Enfield two-piece stock, was a short length of barrel, with front sight guards and lugs for a socket bayonet that was left exposed by a shorter forearm. Despite its heavier barrel, the new rifle was 4 ounces lighter than the No. 1 and was not only faster and cheaper to produce, but displayed superior handling characteristics and improved accuracy in the field.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The No. 4 rifle fired the standard .303 Mark VII cartridge. This had been adopted in 1910 and consisted of a rimmed, bottle-necked case 56mm long loaded with a 174-grain FMJ spitzer bullet with a muzzle velocity of 2,440 feet per second (fps).

The outbreak of World War II prevented full reequipping of the British Army with the No. 4 rifle, and most units continued to use the No. 1 rifle. Production of the No. 4 was undertaken at RSAF Enfield, Royal Ordnance Factories (ROF) at Fazakerley and Maltby and Birmingham Small Arms (BSA). As demand outstripped production facilities in the UK, both the Long Branch Arsenal in Ontario, Canada, and the Savage Arms Company in Massachusetts began production of No. 4 rifles for the Canadian and British armies.

Simplified Design

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Changes began appearing in the No. 4 almost immediately as the different manufacturers attempted to make the rifle easier to produce. More and more stamped metal parts were used, a simple L-shaped flip-up rear sight with apertures for 300 and 600 yards was adopted and barrels were made with two-groove (instead of four-groove) rifling.

Instead of a blued finish, the rifles were Parkerized or used a baked-on enamel finish. Walnut stocks were replaced with ones made from beech and birch. These modifications first appeared on Canadian and U.S.-made rifles, leading to them being designated the “Rifle No. 4 Mk I*.”

The bayonet was simplified with the cruciform spike being replaced by the Mk. II, Mk II* and Mk III bayonets, which were simply sharpened rods. These were unpopular as they were not capable of performing the bayonet’s most important task during a deployment—opening ration tins.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Besides the original Mk. I rear sight, which was machined from steel and had a fine adjustment knob and the simple L-shaped Mk III sight, No. 4 rifles can be found with Mk III, Mk IV, C Mk II, C Mk III and C Mk IV sights. While similar to the Mk. I sight they were made from stamped steel and elevation adjustment was by means of a simple spring catch. No. 4 rifles were first issued to British troops in the Spring of 1942 and they proved even better battle rifles than had the No. 1 Mark III, which was no small feat given the earlier rifle’s well deserved reputation.

During the war, sniper rifles were assembled by BSA and the firm Holland & Holland from No. 4 rifles selected for their accuracy; each was fitted with a No. 32 Mk I telescopic sight and a cheekpiece stock. Two versions of the rifle were assembled: the No. 4 Mk I (T) and No. 4 Mk I* (T).

By 1943 production of No. 1 rifles had ended, except in Australia and India, whose armies declined to accept the No. 4 as they felt the cost of retooling their respective production facilities would be prohibitive. Both nations continued to produce and issue the No. 1 throughout the war years and in some cases well into the 1970s.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

By 1944 most British troops had been rearmed with the No. 4 rifle, and the No. 1s were withdrawn from service and relegated to war reserve status. Besides England, the No. 4 rifle was the primary rifle of the Canadian Army, and they were supplied to the Free French, Greek, Dutch, Belgian, Polish, Czech and Norwegian units fighting alongside the British Army. Savage also supplied about 40,000 No. 4 rifles to the nationalist Chinese government. By 1945 over 3.5 million No. 4 rifles had been produced, with BSA and Savage accounting for almost 80 percent of the total.

Going Global

After the war, the British Army rebuilt many No. 4 rifles with Mk I rear sights and new stocks. In 1947 Enfield developed a new trigger unit for the No. 4 that pivoted on the underside of the receiver, instead of the triggerguard, and required that modified rifles have a new forearm installed. Thousands of No. 4 Mk I* rifles were updated with the new trigger, while new purpose-built rifles, designated the No. 4 Mk II, were assembled at the ROF. Mk II rifles were generally issued with the No. 9 Mk. I bayonet, which featured a much more practical 8-inch, Bowie-type blade.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The improved rifle, No. 4 Mk II, remained the standard British service rifle into the late 1950s, when it was replaced by the 7.62mm L1A1 (FN FAL) semi-auto rifle. British-supplied No. 4 rifles saw service with government forces during the bloody Greek civil war, and it was the standard rifle of the British and Canadian contingents serving with UN forces during the Korean conflict. It also saw wide use by both Israel and its Arab adversaries during fighting that characterized the founding of the Jewish state.

Many of these rifles were used by the French Army during their unsuccessful campaigns against nationalist forces in Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. They were widely used by both Dutch forces and Indonesian nationalist guerillas during the fighting in the Dutch East Indies. Until it was replaced by Soviet weaponry in the 1960s and 1970s, No. 4 rifles were used by the armies of Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Iraq and Pakistan. They showed up in all of the conflicts that raged across the Middle East, North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia and are still seen today in the hands of gue-rilla fighters in all these regions.

It should be noted that until 2015 the No. 4 was the standard-issue rifle of the Canadian Rangers. Composed mostly of Inuit volunteers, they are a sub-component of the Canadian Forces reserve and provide a military presence in Canada’s sparsely settled northern, coastal and isolated areas.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

On The Range

For this article I test fired a No. 4 Mk II rifle from my personal collection that was made at the ROF Fazakerley in 1955. It is in like new, unissued condition with a mirror-bright bore, although the trigger pull was a bit on the heavy side.

Test firing was performed from a Caldwell Lead Sled on my club’s 100 yards with Remington/UMC and Serbian-made PPU .303 British ammunition, both of which approximated the ballistics of the Mk VII cartridge. Folding up the rear sight, I sent the aperture on 200 yards and proceeded to fire for score. The heavy trigger required a bit of nursing along, but once I had the measure of it, I proceeded to produce a half-dozen five-shot groups in the 2.5- to 3.75-inch range, printing dead-on to point of aim.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After I was done with the accuracy testing, I scrounged a dozen drink cans from the range dumpster and placed them on the 50-yard backstop. I then ran the No. 4 through a series of off-hand, rapid-fire drills. The bolt was fast, smooth and positive in operation—as Lee-Enfields have been known for since the 1890s—and reloading with five-round chargers proved quick and easy, allowing me to maintain an impressive rate of fire and make the cans dance to my tune at the range.

- RELATED STORY: .22 Short Magazine Lee-Enfield

After policing up the punctured cans and depositing them in the dumpster, I paused and thought about the Lee-Enfield. This rifle of rifles served king, queen and country for seven decades and its place in the history of the British Empire borders on iconic. Every time I see one, I am reminded of that stereotypical British sergeant-major we have seen portrayed so many times on the screen. Tough, rugged and maybe just a bit rough around the edges—but very good at what he does. Both he and Lee-Enfield got their reputations the old-fashioned way. They earned them!