Sure, the AR has been the longest-serving military rifle in U.S. history, and, sure, it is extremely popular. But before you had plastic and aluminum you had 10.5 pounds of wood and steel, a semi-automatic rifle that immediately announced itself with authority when you picked it up and fired it, leaving no question of its efficacy and power.

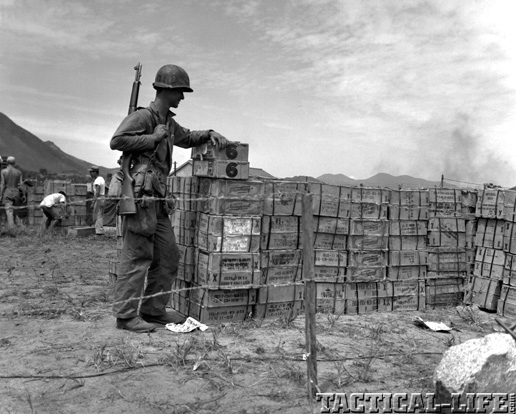

The M1 Garand was the first semi-auto issued to American fighting men when our enemies and allies were mostly carrying bolt-action rifles little different from those of World War I. This revolutionary design was adopted by the U.S. military in 1936, after more than a decade of development and even then saw some key changes before ending up as the rifle carried to victory in WWII and Korea. The M1 Garand was so successful that it continued to see use in Vietnam and with reserve troops into the early 1970s, although as a frontline-service weapon it had been officially replaced in 1957. Into the 1980s, the Garand was still in use by the militaries of numerous friendly nations, ones we equipped with the weapon, including the Greek army.

Garand’s Coming

Designed by Canadian-born John C. Garand, a longtime Springfield Armory engineer, the rifle that bears his name is a long-stroke, gas-piston-operated, eight-shot-clip-fed, semi-automatic rifle chambered in the same .30-06 cartridge as its predecessors, the 1903 Springfield and the M1917 Enfield.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The long-stroke piston on the M1 is similar in concept to that found on the AK-47 and constitutes a long, steel operating rod that forms one piece with the charging handle and joins the rotating bolt, which features two locking lugs on its face. When firing the operating rod, the handle and the unlocked bolt move back as one unit, improving the rifle’s reliability in field conditions but also theoretically reducing its precision. (The bolt handle can also serve as a forward assist to properly seat a round.) Nevertheless, the M1 was considered very accurate and used in the sniper role with scoped variants.

It is possible that Mr. Garand may have come up with different features on his rifle, if left to his own devices, but the terms of what the military contract called for set the stage. The most off-putting feature to our modern eyes is undoubtedly the Garand’s clip mechanism, which the military demanded in lieu of a removable magazine. Although many people use the terms interchangeably, a clip and a magazine are not at all the same: A magazine holds the ammunition to feed into the gun; a clip holds the ammunition to be loaded into the magazine.

The M1 Garand has a fixed internal magazine fed from the top with a spring metal clip that holds eight rounds. Without the clip, the M1 becomes a single-shot weapon that can only load one round at a time. The eight rounds are staggered in the clip, and there is no top or bottom, so it doesn’t matter on which side the top round is located—handy for a battle rifle. On the last round fired, the clip automatically ejects and the bolt locks to the rear. A full or partially full clip can also be manually ejected by retracting the bolt and depressing the clip latch located on the left side of the receiver. Two- and five-round clips are also commercially available.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Operating the M1 is simple but takes a bit of practice at first. Once the bolt is locked to the rear, a full magazine is inserted through the top of the receiver and pressed down. The bolt then automatically releases to go forward and load the first round. It is best to do this with the thumb of the right hand, while using the palm to hold back the bolt handle. Otherwise, the bolt could slam onto your thumb with some force. The safety catch is also somewhat novel. To engage the safety on the M1, depress the metal catch in front of the triggerguard towards the trigger. This moves the steel tab into the triggerguard. When you are ready to fire, simply place your finger in the triggerguard and push the safety bar forward and out of the triggerguard area.

The final gas system adopted for the M1 uses a hole in the bottom of the barrel toward the front of the rifle, to divert gasses against the front of the operating rod. The short gas tube located underneath and at the front of the barrel was made from stainless steel, to help prevent corrosion, and then painted black since the stainless steel would not be easily parkerized. This accounts for the difference in finish on this part of the rifle. It should also be noted that a lot of military .30-06 ammunition is corrosive: it has sodium in the primer and requires the use of water to clean properly and prevent rust. The M1 can weigh from 9.5 to over 10 pounds empty, depending on the type of wood used. Add a sling and a buttstock cleaning kit and the scales tip even more. Of course, this much weight soaks up a lot of recoil, which helps with weapon fatigue and faster followup shots.

During WWII, Springfield Armory (the government armory, not the Springfield Armory we know of today) and Winchester Repeating Arms produced millions of Garands. After the war, production continued, with samples produced by Springfield Armory, Harrington & Richardson Arms and International Harvester Corporation. Almost every M1 has undergone some sort of arsenal repair or rebuilding, which often included new barrels and replacement parts from different manufacturers. Even Beretta produced Garands, using Winchester machinery after WWII, and Beretta parts can be found on M1s imported from service with European armies.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Overseas and Back

I have owned several Garands, all purchased though the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP). These differ significantly from the M1s that may have found their way back to the U.S. from commercial importers: these are all genuine U.S. Government surplus weapons with no annoying import marks, that have been inspected, repaired and test-fired by CMP armorers. The rifle used for this evaluation was purchased almost a decade ago and handpicked by me at the CMP facility in Camp Perry, Ohio.

Based on the serial number, I know that my Garand was built by Springfield Armory in March 1943. It was re-barreled post war, and the new barrel is also by Springfield Armory, dated November 1946. It was sold by CMP as a “Greek issue,” meaning that this rifle was loaned to the Greek government and returned to U.S. military stockpiles at some point, possibly in the 1980s or 1990s. The most common lend/lease foreign Garands offered by CMP are either Danish or Greek issue, although these supplies have already run dry. They don’t command as much as “American” Garands because they may contain European wood or parts. Mine seems to have an original walnut stock and mostly all U.S. parts. There were a lot of Garands and M1 Carbines we left behind in Korea, and many of these found their way to the U.S. through commercial importers in the early 1990s. Having inspected many of these at the time, I can attest that they were in serviceable condition with Korean unit markings on the stocks. South Korea still has a large number of Garands and M1 Carbines they would like to export back to the U.S., but they are facing a good deal of resistance from our State Department, especially in regard to the carbines.

On The Range

Maintenance and disassembly of the M1 Garand is straightforward, although at first glance it does seem like there are a lot of parts to keep track of, which must be assembled in the correct order. Also, it is best to assume that any ammunition you use, with the exception of modern commercial ammunition, is corrosive and to clean accordingly.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

On the range, the old warhorse performed well, with no malfunctions and using a mix of Greek-military surplus ammunition (also purchased from CMP) and modern, commercial hunting ammunition. The front blade sight is fixed, but the rear peep sight is outstanding with elevation adjustments in 25-yard increments out to 1,200 yards and easy windage adjustments. Mounting a scope on a Garand is no easy task, and in order to keep the rifle as close to original as possible, I stuck with iron sights. This is a large heavy rifle and I can’t say that I would have relished carrying it in combat or anywhere else for that matter—it’s easy to understand why many American soldiers preferred the M1 Carbine. Still, the rifle is very well balanced, shoulders easily and has a recoil that, for this full-sized battle round, is very manageable.

Accuracy on the range, firing at 100 yards from a benchrest and using the standard iron sights, was very good—as good as most of the scoped ARs I shoot. My best group was a pretty impressive 1.4 inches, using Remington ammunition. But the Greek 1980s-vintage surplus stuff also produced a 1.4-inch group. Keep in mind that this is out of a circa-WWII, semi-auto, beat-up, rebuilt, Greek loaner rifle using ammunition that was made in Greece when Jimmy Carter was president.

Wrap Up

Many variants of the M1 Garand were created during and after WWII, including a never-issued tanker and paratrooper model, select-fires and ones with detachable magazines. Some were also chambered and issued in 7.62x51mm NATO, especially once the .30-06 round was phased out. The best place to get a real American M1 Garand is still through the CMP, and they have various grades available, although supplies are dwindling. Rack-grade Garands are the cheapest and have the most replacement parts and wear. The color of their metal and wood may not match, and they will have the least finish, the most throat erosion and worn barrels. They can also have foreign replacement parts, pitting of the metal and damage to the stock. The rifle pictured here is a rack-grade gun that was handpicked—the only thing I’ve done to it is lightly refinish the wood to remove some of the scratches and gouges.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Of course you can buy a better field-grade, service-grade, correct-grade or even collector-grade rifle for a premium. Each CMP rifle is shipped with a safety manual, one 8-round clip and a chamber safety flag. Criteria for a qualified purchase are manageable to meet, and CMP ships the rifle directly to your door. To learn more please visit thecmp.org or call 256-835-8455.