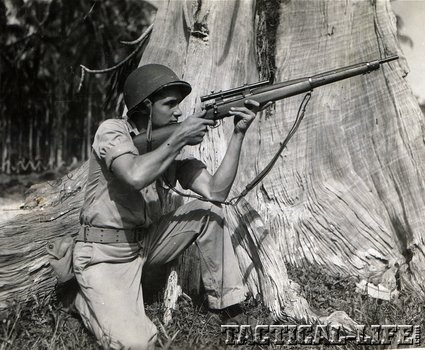

The M1903 Springfield was for many years considered the best bolt-action military rifle ever made. However, note how far forward the rear sight is located, which many found difficult to use under combat conditions.

In 1898, when U.S. troops went to Cuba to fight in the Spanish–American War, they were armed with the .30-40 caliber U.S. Krag rifle. Unfortunately, the Krag was less effective than the M1893 Spanish Mauser, which had longer range and could be loaded more quickly using stripper clips. The Krag’s issue with range was partially due to the fact that, with just a single locking lug, it was not designed to handle newer high-pressure cartridges. While regular Army units were using the Krag, some National Guard units were still armed with the M1873 “Trapdoor” Springfield, and Navy sailors and Marines with the Lee Model 1895 and the Model 1885 Remington-Lee. All of these weapons came up short when compared with the Spanish Mauser. The ones that were captured were examined, and later some of their features were incorporated into a prototype for a new U.S. rifle—it was ready in 1900.

Safety of the M1903 in fire-position.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

.30-03 to .30-06

With some modifications to the prototype, the new rifle went into production in 1903. A new higher-pressure cartridge, the .30-03 round, which used a round-nosed 220-grain bullet, was developed accordingly. To handle the more powerful cartridge, the M1903 bolt had dual locking lugs. Other features included a five-round internal magazine that could be clip-fed, as well as a magazine cutoff that allowed rounds to be fed singly into the chamber while the five rounds in the magazine were held in reserve. Originally, the M1903 had a rod bayonet that slid into the forend, but that was soon deemed too fragile for real combat and replaced with a blade bayonet early in production. In 1906, the round-nose .30-03 round was itself replaced by a more effective spritzer-style bullet. The round was re-designated the .30-06, which remains one of the most popular U.S. rifle cartridges today. Some features of the rifle were licensed from Mauser, while the spritzer bullet was licensed from DWM.

The bolt is back and the stripper clip is in, waiting for the cartridges to be “stripped” into the magazine. Running the bolt forward will knock the stripper clip free.

At the time the .30-06 cartridge was adopted, it was also necessary to adopt a new rear sight regulated for the higher velocity round. The new sight had a scale, or ladder, sight graduated to 2,400 yards, though the slider containing the aperture sight could really only be raised to 1,900 yards. When the ladder sight was down, a battle sight employing an open notch could be used for a quick snap shot. However, since the zero for the battle sight was 547 yards, troops using the battle sight had to be aware of how high or low to hold when taking a quick shot. Rifles that had been issued in the .30-03 chambering were recalled, re-chambered and fitted with the new sights.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

M1903 Springfield

The M1903 was originally produced at Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal. By 1913, enough M1903s had been produced to meet the needs of the U.S. armed forces and to have enough rifles in reserve. As a result, Rock Island Arsenal ceased production. However, once the U.S. entered World War I, Rock Island resumed manufacturing the weapons.

Note that during WWI the rapid increase in M1903 production resulted in heat-treating problems with some receivers, which could cause them to fail. Improved “double heat-treatment” on newly produced M1903s solved the problem. However, care should always be taken with Springfield Armory M1903s with serial numbers below 800,000. Many of these Springfields will have no problems, but there is no sure way to tell. Many early M1903s will have a visible hole drilled in the receiver near the breech, done when the weapon was overhauled. Known as the “Hatcher Hole,” it was intended to relieve gas pressure in the event a case ruptured. Some early rifles were fired with overpressure proof cartridges as well, to identify and eliminate M1903s with poorly heat-treated receivers.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In WWI, the troops’ major complaint about the Springfield was that there were not enough of them. Many troops had to be equipped with M1917 Enfields in .30-06 when most would have preferred the M1903. Those troops equipped with the M1903, especially the Marines, proved formidable. Germans advancing on U.S. lines were decimated by accurate, rapid rifle-fire at ranges considered beyond the danger zone—again and again, U.S. troops armed with Springfields accurately engaged the Germans at long range. During WWI, to increase the firepower of the M1903 the Pederson Device was invented. A semi-automatic mechanism that replaced the rifle’s bolt and fired a .30 caliber pistol cartridge from a 40-round magazine that fed from the top, the Pederson Device converted the M1903 to a fast-firing, close-range weapon. There were plans to arm large numbers of U.S. infantrymen with M1903s equipped with Pederson Devices for a massive offensive, in the event WWI continued into 1919.

Between WWI and WWII, the M1903 Springfield remained the U.S.’s service rifle and primarily saw action with the Marines in China and in the Banana Wars. As of 1936, the M1903 was replaced with the M1 Garand, though many units remained armed with the M1903. In fact, the Marines, not wanting to give up their highly accurate Springfields, did not initially adopt the Garand. It was not until the latter years of WWII that there were enough Garands produced to replace the M1903s. In fact, some troops remained armed with them until the end of WWII: On Guadalcanal, the Marines began their march to Japan armed with M1903s. But once they saw the Garand at work in the hands of Army troops who had subsequently arrived on Guadalcanal, the Marines adopted the Garand. Yet, even after many units had replaced the M1903 with the Garand, grenadiers continued to use the M1903 until a grenade launcher was developed for the Garand.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

M1903 Variants

The M1903 went back into production at Remington in 1941. Then to speed output, the M1903A3, which used more stamped parts and a less-expensive wood stock, went into production in 1942. Although most purists like the earlier M1903 and the M1903A1, which was similar to the M1903 but with a pistol-grip stock, many troops preferred the A3’s rear sight, which was located further to the rear of the receiver and offered better eye relief.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Although sniper versions of the M1903 had been developed prior to and during WWI, the best-known sniper model, and the primary U.S. sniping rifle in WWII, was the M1903A4. Based on the A3, the A4 had a different stock and an M73 or M73B1 2.75x Weaver scope. The A4 would continue in use during the wars in Korea and in Vietnam. (In Korea the M1C Garand sniper rifle was also used. In Vietnam various other sniper rifles were used, including the M1D Garand and the M14 sniping rifle, which became known as the M21.)

Some M1903s remained in service on Navy ships at least into the 1970s. They were used for shooting at mines but could also be issued to boarding or shore parties or for other security tasks.

Reliving History

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I have always enjoyed shooting the M1903. In fact, the first U.S. military rifle I owned was an M1903 Springfield. In those days, surplus .30-06 ammunition was around and I shot it quite a bit. I did a book on the M1903 a few months ago, and one of the real benefits was that I got to take my Springfields out of the safe to reacquaint myself with their shooting characteristics. I’ll quickly summarize some of the more noteworthy aspects of shooting the Springfield.

As has already been mentioned, the rear sight on the M1903A3 is located further back and is easier to acquire. On the M1903 and M1903A1, the sight is forward, in front of the bolt, which creates eye relief that is really too long. Using the standard M1903 rear sight takes some familiarization. For a quick shot, the battle sight may be used, but it is zeroed at 547 yards on the typical M1903s from WWI and the 1920s. At longer ranges the U-notch on the slider may be used when the ladder is up. Also, the ladder may be flipped up and another U-notch or aperture may be used for closer-range engagement. It takes some practice to learn which sight best suits which distance.

Loading the magazine from stripper clips is fast and reliable, as soon as you get used to thrusting the clip into the clip guide and then giving a sharp thrust with the thumb to push the cartridges into the magazine. On the original M1903—but not on the A3—it is unnecessary to remove the stripper clip—running the bolt forward will knock it out and chamber a round. However, if the magazine cutoff is to be used so that single shots may be fired without using the magazine, then the stripper clip will need to be removed and the cutoff set to “off.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The best way to operate the bolt is with the palm of the hand for pushing forward and locking, as well as for unlocking and pulling backward. Use of the palm is faster and grants more leverage when locking or unlocking the bolt. With practice, the bolt may be operated without losing the sight picture, though I have found that, unless I push the butt tight against my shoulder, it may shift slightly during operation of the bolt.

Collectible M1903 Springfields can bring $1,000 or more these days, but good shooting examples may be found for $500 or less. Quite a few have been sold by the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP) over the last decade, and many of these have been M1903A3 rifles, which as I’ve mentioned some shooters prefer. Some years ago, the CMP had noncorrosive .30-06 ammunition packed in Garand clips. I bought quite a bit of the ammo and have removed some from the Garand clips and put them in M1903 clips to use with my Springfield rifles.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I think what I like most about the M1903 Springfield is that it was developed during the days when the U.S. still considered itself a nation of riflemen and gave them what most consider the best infantry weapon of its day. That day may have been a century ago, but I still appreciate the M1903. Just handling one conjures up images of my father who fought in WWI and served in the U.S. Army during the 1920s. I have a photo of him with his M1903, so I feel a link when I handle mine. All the nostalgia is good, but it is also an excellent rifle.