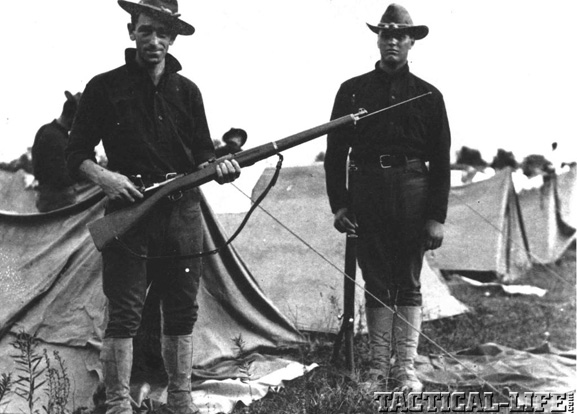

It was brutally obvious to the U.S. military that the Spanish forces were better equipped: The Model 1898 Krag-Jorgenson rifle was no match for the Model 1893 Mauser. More than 15,000 U.S. troops attacked 1,270 entrenched Spanish forces at San Juan Hill and El Caney outside Santiago, Cuba, in the tropical heat of July 1898. Over 200 U.S. soldiers were killed, and nearly 1,200 were wounded from the fire laid down by the Spaniards’ Mausers. The U.S. military needed a solution, which would officially become known as the United States Rifle, Caliber .30-06, Model 1903.

The M1903 Springfield, as it is commonly called, would serve the U.S. military from 1903 to 1974, participating to varying degrees in World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam and other minor but no less lethal conflicts, earning a reputation for reliability and accuracy. Part of the lore of these rifles are the numerous design variations and its chambering in the quintessential American cartridge, the .30-06. M1903 scholars and collectors read cartouches and markings like hieroglyphics, to decipher each variation and debate the number of rifles built. Here’s how they all began.

Opening Design

After the brief Spanish-American War, the U.S. military wasted no time analyzing captured 1893 Spanish Mausers—they did not want to be caught flatfooted with outclassed equipment again. The Mauser’s edge was its ability to quickly reload via a stripper clip, while the Krag rifle was loaded one round at a time. The .30-40 Krag caliber was outclassed too: The 7x57mm had a farther effective range and was more accurate. In 1900, the U.S. finalized a design that borrowed many features from the Mauser, including a fixed internal magazine, a dual-forward lug bolt, a bolt-mounted safety and a magazine cutoff. But an effort was made by the U.S. military to also differentiate the new design from the Mauser, with a two-piece firing pin and a third safety lug, among other details.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The weapon also had a few Krag-Jorgenson-rifle characteristics like the ladder-type rear sight. Production began in 1903 (hence the name), at the federal armory in Springfield, Massachusetts. When Mauser became aware of the M1903, it filed a patent infringement lawsuit in U.S. courts and won. It is unclear whether the U.S. government made restitution, but after the U.S. entered WWI, all bets were off—Germany was our enemy. But that’s getting ahead of the tale.

Off the Ground

The first M1903 featured a sliding rod-style bayonet under the 24-inch barrel and weighed close to 9 pounds. It was chambered for the .30-03 cartridge, which propelled a 220-grain round-nose bullet at an approximate velocity of 2,300 feet per second (fps). The .30-03 was only 100 fps faster than the .30-40 Krag round and ballistically no better than the .30-30 Winchester. In the meantime, French and German militaries were moving to spitzer-style or pointed bullets. From the start, the M1903 was nearly obsolete.

A flat-blade bayonet designated the M1905 was designed to replace the M1903’s rod bayonet. The military then decided to improve the sights and, just as Springfield Armory was finished retooling for the M1905 bayonet, with another significant change: The M1903 was to be re-chambered for the new Cartridge, Ball, Caliber .30, Model 1906, or .30-06. Re-chambering also meant the sights needed to be reworked (again) to match the new ammo’s trajectory. Other minor design changes were still to come, but by 1906 the M1903 Springfield was combat ready—and just in time. In 1917, the U.S. entered the Great War that had been raging in Europe since 1914. About 840,000 M1903s were already built by Springfield Armory and by Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois, but the U.S. had an urgent need for more rifles.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

At this point, the legend takes a turn. Remington and Winchester were producing Enfields for the UK, so the decision was made to not retool factories for the M1903 but use the existing toolings and re-chamber the Enfield in .30-06, which they called the M1917.

Of the M1903s that had been produced, the metallurgy of those early M1903s was questionable: Receivers were case-hardened and brittle, and some receivers did fail. (These rifles can be identified by their serial number: Springfield guns have a serial number under “800,000,” and Rock Island gun are below “285,507.”) Supposedly, the military tested these low-numbered rifles, and those that passed were re-issued—those that failed were taken out of service.

From Teddy TO FDR

The M1903A1 was the first model that changed the M1903’s straight grip to a pistol-grip stock. A M1903A2 model was adapted to fire rifle rounds through artillery. Production of the M1903A1 was mothballed through the 1930s then resumed in September 1941, when the U.S. military contracted with Remington. It was WWII. Germany was racing across Europe and another threat was on the Pacific’s horizon, on that “day of infamy” at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Both Remington and Smith-Corona, a typewriter manufacturer, began production and offered design changes that were adopted in the M1903A3, the last M1903 variation issued in large numbers.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The M1903A3 used stamped-metal parts to replace machined parts, a different stock, a two-groove rifled barrel, an aperture sight mounted on the receiver and other changes to speed production and reduce cost. Soon after came the next variation, a dedicated sniper rifle designated the M1903A4, with a Weaver Model 330 scope on Redfield mounts, which replaced the earlier model’s iron sights. Since the M1903A4 used a two-groove rifled barrel, it was not especially accurate for a sniper rifle. A Bushmaster carbine with an 18-inch barrel was also produced, but it saw no combat use.

Other variants over the years of the rifles’ production include the Hoffer-Thompson-modified M1903, which fired .22 rimfire ammunition. A few national match rifles were also produced, as well as .22 training rifles. Experimental models included the M1903 Mark I with the Pedersen device, which swapped the bolt for a mechanism that allowed semi-automatic fire and had a 40-round detachable magazine that used a .30 caliber pistol-size cartridge. For trench warfare, an M1903 was modified with a periscope, so soldiers could fire the rifle while safely hidden in the trench.

After the wars, the M1903 was sold off to military surplus liquidators and some took on a new life as hunting rifles. Ernest Hemingway, Teddy Roosevelt and countless other big-game hunters used customized Springfields. Today, a few military drill teams use the M1903, but these are inert weapons rendered incapable of firing or dummy rifles that look like M1903s.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Brass Tacks

The 1903A3 used for testing was built by Remington and bears a serial number and barrel markings indicating it was produced in May 1943. The cartouche on the left side of the stock is worn, but the rifle appears to have been rebuilt at San Antonio Arsenal (SAA). The block letter “P” stamped in the wood behind the triggerguard indicates it was proof-tested once and ready for acceptance by the military.

The Mauser design is evident in the controlled-feed claw (hook extractor) and the two lugs on the bolt. There is a third safety lug located roughly in the middle of the bolt, which cams against the rear shoulder of the receiver. The rife is cocked by lifting or opening the bolt handle or by pulling the cocking piece rearward until it locks. The internal magazine has a cutoff switch that is clearly marked “on” and “off.” Flip the cutoff up in the “on” position to allow the bolt to scrape a cartridge from the magazine and into the chamber. In the “off” position, the bolt cannot be drawn fully rearward, so cartridges are held under the bolt. The M1903A3 (like all M1903s) can be loaded via a five-round stripper clip. To charge the magazine, the cutoff needs to be placed in the “ON” position, then open the bolt fully rearward and insert either end of the stripper clip into the slot in the receiver and press the cartridges down into the magazine. I purchased a handful of stripper clips from Numrich (gunpartscorp.com; 866-686-7424) and found it was just as easy to singly load rounds into the mag as it was to charge the magazine with a clip. Pushing the bolt forward after charging the cartridges ejects the stripper clip, or it can simply be pulled free from the receiver slots. The safety lock, also similar to the Mauser’s, is a large lever clearly marked “ready” when rotated fully to the left, indicating the rifle is ready to be fired. Rotate the safety fully to the right, and “safe” is indicated on the lever. The bolt and trigger are locked in place. The rear aperture sight slides up and down a ramp, locking in place via detents to adjust elevation. Graduations are marked from 1 to 8 (100 to 800 yards). Windage is adjusted via a knob on the right side of the sight. At the base of the sight are graduations lines to indicate left/right adjustment.

My best guess is this 1903A3 was purchased at a Sears in the early 1960s. I have no idea when the last time the rifle was fired, so I used a one-piece Dewey rod and plenty of solvent. On inspection, the two grooves of the rifling were bright and sharp. The front blade sight was bent either for someone with bad astigmatism or from sloppy handling. Either way, the blade was a weak spot—this was before protective wings were commonplace—but a pair of pliers corrected it. The bolt operated effortlessly and flawlessly, more so than many contemporary bolt-action rifles—I could easily palm it for fast followup shots. Of course, I have no idea what this particular 1903A3 did a half-century ago.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Test Drive

A minor gripe with the M1903A3 and other variations is the straight stock, as recoil is directed back into the user’s shoulder. An old-timer who was a swabby suggested I place a folded dishtowel between my shirt and the Springfield’s steel buttplate. You can feel the kick from modern, juiced .30-06 cartridges, but it was not particularly noticeable with mil-spec ammunition—the rifle’s heft eased the bite.

Starting out at 50 yards, I was able to gut-shoot a silhouette target with a group no bigger than an iPhone, without really trying. As I moved higher up, the Federal American Eagle loads placed three rounds in the chest. Three rounds of the Federal Premium were all headshots—I was pleasantly intrigued this old war dog still had teeth. At 100 yards, a target with a white background was used to better see the front blade. The rifle seemed to like the PPU ammunition and absolutely loved the Federal Premium with 180-grain Nosler Partition bullets — a group of four holes mesured 0.87 inches until a flyer ruined it. The Federal Eagle and PPU were loaded with 150-grain FMJ bullets similar to mil-spec cartridges. As I became accustomed to the recoil and the two-stage trigger, which broke at 5.3 pounds on average, groups began to shrink. The barrel heated, and the handguard sweated cosmoline. The faster I cranked the bolt and fired rounds, the more the M1903A3 seemed to like the exercise. I now understand why so many servicemen liked the weapon. I was in the presence of a legend.

Special thanks to the Springfield Armory National Historic Site (nps.gov/spar) for their assistance and photographs.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below