Some of today’s shooters think any pistol that debuted in the year 1911 simply must be obsolete, and should be relegated to the museum instead of the working armory. Yet today there are more companies manufacturing 1911s—and more individuals keeping them as home-protection guns and carrying them as personal weapons—than ever before. Critics are at a loss to understand why this is. We who still carry them are not.

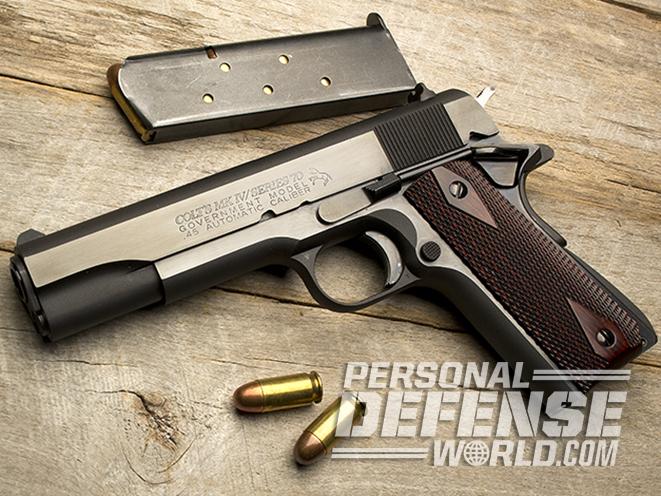

The Model 1911 was introduced in what would be its defining chambering, the .45 ACP. By the start of World War II, it had also been chambered for the deep-penetrating .38 Super (since 1929) and the .22 LR, in both conversion kits for standard guns and the dedicated Colt Ace pistol. Today we can buy 1911s at gun shops chambered for all three of those cartridges plus the 9mm, 10mm, .40 S&W, .357 SIG, .22 TCM, .50 GI, .45 Super, .45 Winchester Magnum and .357 Magnum in the Coonan pistol. In the past, 1911s were manufactured in 7.65mm Luger and 9mm Steyr for the overseas market, and in 9x29mm (aka the 9mm Winchester Magnum). Wildcat rounds developed for the 1911 include the .41 Avenger, the .460 Rowland and the .38-45. And I’m certain I’ve missed a few more.

Ultra-Versatile

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The 1911 can do a number of things well. The late Hal Swiggett, the first editor of The Complete Book of Handguns, shot many deer with the Colt .45 ACP that always accompanied him on his travels. And while the pistol wasn’t designed for hunting, I killed my last wild hog with a Smith & Wesson SW1911 .45, and have Saint Patrick’d my share of poisonous snakes with various 1911s in 9mm through .45 ACP.

Target shooting has embraced the 1911 for a century or so. In Bullseye competitions under the auspices of the NRA, the 1911 is the standard choice for the .45-caliber third of the game, and it’s hugely popular in the centerfire third, and many competitors choose custom rimfire 1911s even for the third of the course dedicated to rimfire .22s.

- RELATED STORY: The Top 11 1911s That Caught Our Eye in 2016

From the custom Colt .45 ACP of the first winner in 1979, Ron Lerch, to the Smith & Wesson .38 Super of today’s perennial winner, Doug Koenig, the 1911 has won more times at Bianchi Cup matches, the flagship of NRA action pistol shooting, than any other handgun. These pistols are big at Police Pistol Combat (PPC) matches, too, in both 9mm and .45 ACP. They’re huge in Steel Challenge matches as well, and you’ll see more 10mm and .45 ACP 1911-style pistols than anything else at bowling-pin matches, where it takes powerful shots to clear heavy bowling pins completely off the tables.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

On the defensive side of the house, police and law-abiding armed citizens have embraced the 1911 from the beginning. The legendary Texas Rangers bought their own Colt .45s (and later, to some degree, .38 Supers) so enthusiastically that they became something of a trademark gun for the agency, and Wilson Combat has even offered a dedicated Texas Ranger model. By the 1960s, forward-thinking police departments such as those of Los Alamitos and El Monte, California, had adopted the Colt Government Model .45 as standard issue, and many more departments authorized them as privately owned duty weapons or backup and off-duty guns.

Just as generations of American soldiers came back from their wars and bought bolt-action rifles after WWI, autoloading .30-caliber rifles after WWII and Korea, and AR-15s after Vietnam, all of those generations came home already trained to use the GI 1911 .45, and therefore many bought such guns to defend their homes or wear with their carry permits. The writings of Colonel Jeff Cooper in the 1950s and 1960s did much to popularize the .45 as what he called a “fighting handgun.”

Ergonomics

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Buying a gun is like buying an automobile or an appliance: Rather than blind brand loyalty or family tradition, you are wise to assess your needs and buy the machine whose features best fit those needs. Let’s look at what the 1911 offers in that respect.

Spellcheck doesn’t recognize the word “shootability,” but serious shooters most certainly do. The 1911 offers controllable muzzle rise, caliber for caliber, due in large part to its low bore axis, which gives the shooter more leverage to control the gun. The consistent, relatively easy trigger pull is probably the big reason so many gunners shoot 1911s better than anything else. Generations of gunsmithing and institutional history among manufacturers has resulted in superbly clean trigger pulls even out of the box, always with the short trigger travel the great John Moses Browning designed into this masterpiece so long ago. The way the gun fits in the hand is another important factor, and there is a story behind that.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

John Browning’s original Model 1911 had a long trigger. Soldiers and Marines who had fought with the gun in WWI said the trigger reach was too long. In the first quarter of the 20th century, the average man was shorter than today with proportionally shorter fingers. As a result, the 1911A1 modification of the 1920s incorporated not only milling niches into the frame on either side of the triggerguard to reduce how far the finger had to reach, but also a dramatic shortening of the trigger itself. This had an interesting result.

Today, you’ll find that a petite female whose finger might be a full phalange shorter than that of an average-sized male can get the perfect trigger reach on a 1911 that has the short “A1” trigger. An average-sized male with the same short-triggered pistol can get his distal joint onto the trigger face comfortably, which gives him much more leverage to pull the trigger. Ironically, many men found the short-reach trigger too short, particularly if they prefer to fire with the pad of the index finger on the trigger face. Thus, since more men buy guns than women in this society, a huge number of 1911s come with triggers as long as John Browning’s original design. The point is, the many options in 1911 design allow a gun in that format to fit many hands well. Scaled-down 1911s—such as the excellent Springfield Armory EMP in 9mm and the Browning Black Label .380—seem to fit in the smallest of adult hands.

Slim & Safe

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Another endearing feature of the 1911 is its slim profile. It is very thin and flat for a pistol of its power level. This is important to those who lawfully carry concealed, and particularly so for those of us who wear inside-the-waistband (IWB) holsters for maximum concealment. Having carried a 1911, usually in .45 ACP, since I was a kid working part-time in my dad’s jewelry store, this feature has never lost its charm for me. For someone accustomed to wearing a thicker, blockier pistol IWB, well, you just have to try a 1911 in the same carry mode to appreciate the difference.

Safety features abound on the 1911. The serious user will carry this gun “cocked and locked,” with a full magazine, the hammer back and a round in the chamber. This means that the thumb safety has to be pressed down into the “fire” position—a very natural movement for the human hand—before the gun can discharge. Anything from a cover garment’s adjustment cord to a careless user’s finger can catch that trigger as it’s going into the holster, but if the safety is engaged, the pistol will not fire.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

- RELATED STORY: 11 Custom Gun Shops For 1911s

If the shooter puts his or her thumb on the hammer of the cocked-and-locked 1911 pistol when it is going into the holster, a couple of other safety elements come benevolently into play. With the web of the hand no longer pressing on it, the grip safety is engaged and, if properly adjusted, will by itself prevent an inadvertent discharge.

Cocked-and-locked carry also adds another dimension of safety. When dealing with violent criminals, the possibility of the offender disarming good guys or gals and shooting them with their own weapons is always a source of concern. Tests going back to ‘Police Chief’ magazine in the early 1980s showed that with a “point and shoot” handgun, the offender could get a fatal shot off in just over a second after getting the good guy’s gun in hand. But with a cocked-and-locked 1911, it took most people an average of some 17 seconds to figure out which of those levers and buttons on the snatched gun was the one that “turned on the pistol.” This bought the good guy a significant margin of time to either escape or rectify the situation.

Answering Needs

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

If any handgun was the perfect ne plus ultra, all of us would use it exclusively, and like any other machine, the 1911 has a few shortcomings for some. If you want more cartridges on board, Para-Ordnance started the trend of making larger-capacity 1911s, and STI and many other makers carry that banner today.

If you want something a tad lighter, aluminum-framed 1911s have been available since the mid-20th century. Need something smaller? Well, understand that the smaller you go with this particular platform, the more you’re risking reliability issues. You can’t abide having to thumb a safety off before shooting? The 1911 is probably not for you.

But then again, it is definitely the right gun for a lot of people. Comfortable beavertail grip safeties, modern machining processes with tighter tolerances, and better sights and trigger options have made today’s 1911-style pistols the best ever manufactured.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

This article was originally published in ‘The Complete Book of Handguns’ 2017. For information on how to subscribe, visit outdoorgroupstore.com.