At the end of the 19th century, governments around the world began seeing the functional advantages semi-automatic pistols offered over single- or double-action revolvers. As one technology fades out and a newer offering replaces it; there are often designs that fall somewhere in between the two. The resulting devices blend the new with the old. While some are able to adapt and succeed, most end up being relegated to the past as the full potential of a new technology is realized. Such is the case of the semi-auto revolver.

Fosbery Semi-Auto Revolver

In 1895, George Vincent Fosbery, who received the Victoria Cross in 1863 for hand-to-hand combat on the frontier of India with the First Punjab Regiment, developed what he called an “automatic revolver,” with a patent following in 1897. An unusual design, it claimed to be “the result of several years’ experiments to make an Automatic Revolver that can be fired as rapidly as any of the Automatic Pistols now before the Public.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The automatic revolver relied on the gun’s recoil to rotate the cylinder and cock the hammer. The barrel, cylinder and hammer were all part of an upper assembly that moved back and forth on the lower frame of the revolver.

Initially, Fosbery based his design on a Colt Model 1876 revolver. After a couple years of testing, it was clear that the gun would still need improvements. The Colt sear mechanism was abandoned in 1899. Soon after, Fosbery approached Webley & Scott for assistance with his design.

Production began in 1901 at the Webley & Scott factory in Birmingham, England. Because of the partnership, Fosbery’s invention, which became known as the Webley-Fosbery Automatic Revolver, looked very similar to the standard top-break British service revolver of the day. It also fired the standard .455 Webley cartridge. This new design combined the speed of a double-action revolver with the crisp trigger of a single-action revolver. Another selling point was the gun’s ability to fire the .455 Webley cartridge; this made it more powerful than the 9mm-chambered Mauser.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

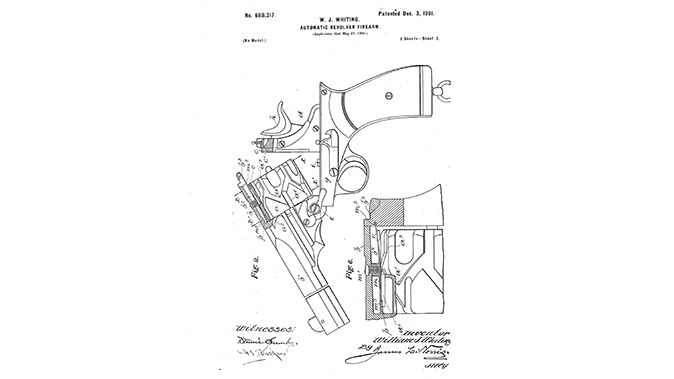

The Webley-Fosbery Build

The zigzag grooves on the revolver’s cylinder are the model’s most iconic visual and functional distinction. Patented by William John Whiting in 1901, the grooves played an important role in the gun’s operation. When the top half of the revolver recoiled to the rear, the cylinder grooves were engaged by a stud on the frame. This engagement provided 30 degrees of rotation. As the recoil spring pushed the revolver forward, the cylinder rotated another 30 degrees and placed a new cartridge in line with the firing pin.

While the design had its advantages, it was not without drawbacks. The Webley-Fosbery was expensive to manufacture and, in turn, expensive to buy. When the gun was made available to the public in 1901, you could buy a Mauser C96 Broomhandle pistol for 10 shillings less than a Webley-Fosbery.

The “make or break” moment for many firearms comes during military trials. Testing for the Webley-Fosbery by the War Department was conducted in May and September of 1901. The report from the president of the Small Arms Committee was not positive. He concluded that the “mechanism proved unsatisfactory in the working” and that even with improvements, the gun would be at a disadvantage to semi-automatic pistols because “it requires to be loaded singly instead of the whole capacity of the magazine or chamber by one motion.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Fosbery’s Fate

Despite the less-than-flattering review from the Small Arms Committee, the gun was well-received in other venues. When the gun made its debut at the Bisley Shooting Ground, it was met with great fanfare and copious amounts of positive press. In 1902, famed target shooter Walter Winans fired 12 shots (including a reload) into a 2-inch group at 20 yards in only 20 seconds. Fosbery accomplished rapid reloading through the use of a Prideaux speedloader.

The attendees at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904 also lauded the design. Unfortunately, commercial approval only goes so far; a military contract was necessary in order for the design to survive. Ultimately, no contract materialized and production of the Webley- Fosbery Automatic Revolver ceased.

During the gun’s entire production, only 4,200 saw the light of day. Of that total number, almost all were chambered for the .455 Webley. Approximately 200 left the factory chambered for the .38 ACP. If Fosbery’s design hadn’t had to compete against semi-automatic pistols for a place in the market, it may well have survived. Ultimately, the Webley-Fosbery Automatic Revolver fell victim to the rapid-paced change in firearms technology during the first half of the 20th century.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Meet the Mateba Autorevolver

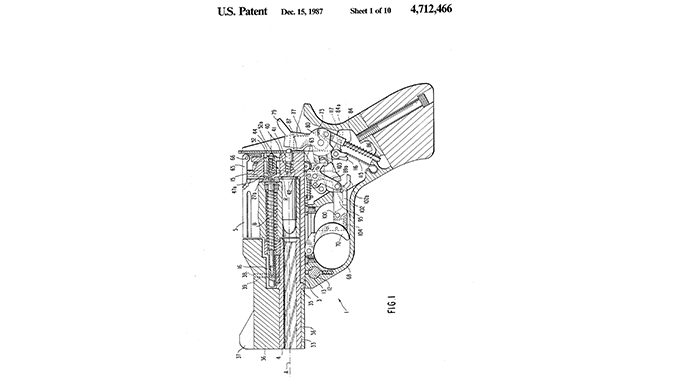

History is a wonderful teacher if you listen to the lessons it has to offer. If not, history tends to repeat itself, as it did with the Mateba Autorevolver. Emilio Ghisoni, the heir to an Italian food processing company, sought to improve the shortcomings of the Webley-Fosbery. His design, which was patented in 1987 and took another decade to reach production, was quite different from its predecessor.

While the Webley-Fosbery looked like a normal revolver at first glance, there was no mistaking that the Mateba was different. The revolver’s steel frame, swing-out cylinder and aluminum barrel shroud were the only aspects of its design that could be considered normal. Visually, it had an interesting shape to the cylinder, an ambidextrous cylinder latch, an extended beavertail, distinctive grips and a compensator. Oh, and it also fired from the bottom chamber of the cylinder instead of the top one, giving it an exceptionally low bore axis.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Mateba Autorevolver Functionality

Its operation was similar to the Webley-Fosbery, though not exactly the same. The cylinder’s large, slab-like fluting and lack of other features were directly linked to the way the gun locked up and how it cycled. Cylinder latches to lock the chamber in place were located on the face of the cylinder instead of the outside edge. This eliminated the notches on the outside of the cylinder and also prevented a drag line from forming.

The first shot was in double action, with subsequent shots being single action. While you could manually cock the hammer for the first shot, it wasn’t necessary. Recoil moved the slide to the rear, cocking the hammer. The forward motion returning the gun to battery rotated the cylinder to the next loaded chamber leaving the gun ready to fire. No cams, studs or zigzag grooves were used to rotate the cylinder.

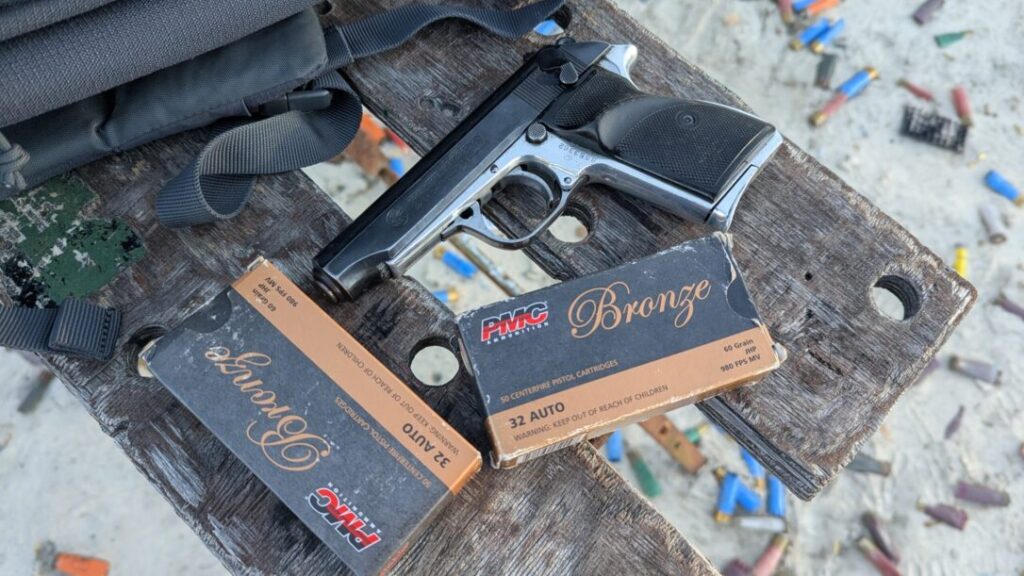

Available in .357 Magnum, .44 Magnum and .454 Casull, the gun’s recoil spring could also be changed to fire .38 Special, .44 Special and .45 Colt ammunition. The spring change was necessary because the less-powerful cartridges were incapable of properly cycling the action for repeated shots downrange.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Different-length barrels were also available to suit the needs of the shooter, including a carbine version comprised of an 18-inch barrel, handguard and buttstock. Generally speaking, the 4-inch barrel was for self-defense, the 5- and 6-inch barrels were for home protection or competition, and the 8.4-inch barrel was for hunting.

Because of the Mateba’s low bore axis, substantial weight of approximately 3 pounds and recoil operation, it is quite a pleasant revolver to shoot. Follow-up shots are easily placed on target with a great degree of accuracy.

End of the Lina

Unfortunately, this wasn’t enough to keep the company in business. Ghisoni failed to learn from the Webley-Fosbery’s mistakes. Ghisoni was forced to sell Mateba to a German firm in the early 2000s. By 2005, the company ceased to exist altogether. All told, fewer than 2,000 Mateba Autorevolvers were ever made.

Nonetheless, Ghisoni’s legacy lives on through the Mateba’s strong fan base and his design influence on another revolver with a unique appearance. It is no coincidence that the Mateba Autorevolver and the Chiappa Rhino look similar. Emilio Ghisoni worked on the Rhino, using his idea for a 6 o’clock firing position on this new revolver. Beyond that, the Mateba and the Rhino are completely different firearms, with the Rhino operating like a traditional DA/SA revolver. Even though the Rhino turned out to be far more successful than the Mateba, Ghisoni wouldn’t live to see it. He passed away in 2008 before the design came to fruition.

Ultimately, both the Webley-Fosbery and the Mateba Autorevolver sought to answer questions nobody had asked. The majority of consumers ignored their answers. With almost a century of innovation between them, the end result was the same: The market had no place for a gimmicky semi-auto revolver when there were plenty of good semi-automatic pistols and standard revolvers to be had.