Among the world’s soldiers for hire, two groups stand out for their history of courage and loyalty: The French Foreign Legion and the Gurkhas. In fact, because they have served one country loyally for so many years, the French Foreign Legion and the Gurkhas are exempt under U.N. protocols regarding “mercenaries.” Gurkhas first entered the forces of the British Empire early in the 19th century, after the Gurkha War (1814–1816) against the army of the East India Company. So impressed were the British that, in the consequent peace treaty, it was stipulated that the British could recruit these soldiers to serve in the East India Company’s army.

From 1857 until 1947, when India gained its independence from Great Britain, the Gurkhas served in the Indian army, seeing extensive combat along the Indian frontier, including in the Third Afghan War (1919), World War I and World War II. During WWII, ten Gurkha regiments served, each with three or four battalions, with a total of 250,280 Gurkhas ultimately serving in the war. At least some received parachute training during this time.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

There is a famous story, which may be apocryphal, but I first heard it from a girl whose father was an officer in the unit. Reportedly, when told they would make their first training jump from 800 feet, a Gurkha havildar (sergeant) asked if perhaps they could make the first jump from 400 feet. However, the British training sergeant replied that the parachutes would not open at 400 feet, to which the havildar replied, “Oh, we will have parachutes. Then it is alright.” No fear.

Later, from 1963 to 1968, there was an Independent Parachute Company.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

India & Beyond

After India’s independence, some regiments chose to serve in the army of India, while others chose to join the British army. The four regiments that chose to stay with the British army formed the Brigade of Gurkhas. Initially, the Brigade of Gurkhas was stationed in Malaya, where they fought in the counterinsurgency war against communist guerrillas.

During the 1960s, Gurkhas fought in Borneo against Indonesian guerrillas threatening Brunei. So impressed was the sultan of Brunei that he later hired 2,000 Gurkhas to serve in the Gurkha reserve unit, which protects the Sultan, his family and oil installations. Two Gurkha battalions serve in the Nepalese army, and the Singapore police has a contingent of Gurkhas who guard key installations and act as its reaction force.

For many years, their regiments were stationed in Hong Kong to provide security along the border with China, but once control of Hong Kong returned to the Chinese, these units were pulled out. More recently, they have served in Iraq and Afghanistan as well as Kosovo. They have also been deployed as part of peacekeeping forces in Bosnia, East Timor and Sierra Leone. Traditionally, Gurkha officers were British, though now a substantial number are Nepalese. Often, the top graduates of Sandhurst compete for a commission in the Brigade of Gurkhas, an assignment that requires learning Gurkhali. Assignments are fewer as the brigade has been cut back to two battalions due to the British army’s downsizing. Four Gurkha regiments were consolidated into the Royal Gurkha Rifles with a current strength of about 3,400. By comparison, up to 100,000 serve in the Indian Gurkha regiments.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Long Live The Gurkhas

Skilled Gurkha warriors later served in both World Wars and today take part in UN peacekeeping missions. If you find yourself betting on who would win in a fight between one Gurkha and 30 Taliban fighters or 40 thieves, better bet on the Gurkha, because both of those situations actually happened.

1. The Selection Process is Intense.

Obviously, elite fighting forces don’t take just anyone into their ranks. Like all true elites, these warriors have a rigorous way of weeding out the weaker applicants. They have all the usual personal interviews and exams, but once completed, the endurance tests begin. The Gurkha school of warfare puts its initiates through grueling runs up Himalayan mountains, often carrying a good load of weight, the physical training program is so difficult that people fall out all day, every day.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Competition to serve in the unit is fierce—30 or more applicants for each opening show up for selection in Nepal. Those who meet basic intelligence, initiative and physical requirements—usually 270 candidates per year—move on to training for either the Singapore police or the British Gurkha Rifles. Those selected receive nine months of training in the UK covering military skills, Western culture and customs, English, weapons proficiency and physical fitness. Those trainees who show special aptitude at mathematics are often assigned to the Queen’s Gurkha Signals or Queen’s Gurkha Engineers.

Female Gurkhas Members

Female Gurkhas serve in the Royal Army Nursing Corps or in some other slots open to female soldiers. Those soldiers who have completed an initial enlistment in the Gurkha Rifles are now eligible to enter other British regiments. At least some have joined other elite units such as the Parachute Regiment and the Special Air Service. Like the red beret of the Parachute Regiment, the green beret of the Royal Marine Commandos and sand-colored beret of the SAS are symbols of elite units; so is the Hat Terai Gurkha worn by Gurkha soldiers. It is normally only worn on parade or special occasions, though. The rest of the time they wear a beret or Kevlar helmet. A contingent of 120 members served with the Parachute Regiment. At one point and wore the maroon beret with the crossed kukris cap badge.

Currently, Gurkha veterans who have completed four years of honorable service are eligible to settle in the UK. Those who reach retirement are eligible for a pension equal to that of other British soldiers of the same rank. Some Gurkhas after leaving the Gurkha Rifles have worked as security contractors. One British former Gurkha officer founded a company that supplies them for security jobs.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

2. Gurkhas live Up to Their Badass Motto.

When going into combat against them, knowing that their motto is “Better to die than be a coward” is enough to make you think twice. And knowing the history, you’d be right to just go around them.

In World War II, a team of Gurkhas became pinned down in a trench, facing some 200 Japanese soldiers. When they started lobbing grenades, Lachhiman Gurung began throwing them back — until one of them blew off his hand. When the Japanese charged his trench, he stood and fought, despite taking massive wounds to his body, leg and arm. Gurung literally single-handedly fought off 31 Japanese soldiers and stalled the entire enemy advance.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

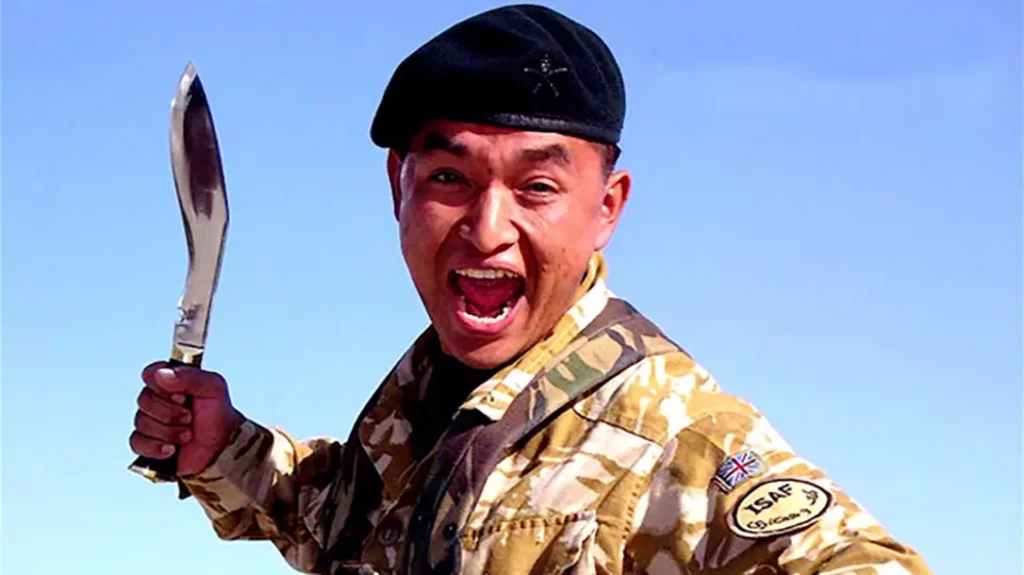

3. The Kukri Knife

Just because you’ve disarmed a Gurkha, doesn’t mean you’ve won. All Gurkhas are trained with the Kukri knife. A distinctive, 18-inch inverted curve blade that is just as deadly as any other weapon.

A Gurkha named Bhanubhakta Gurung — also in World War II — was charging a Japanese bunker in Burma. He had already shot a sniper out of a tree as he charged an enemy bunker. Out of ammo, he cleared the bunker with just two smoke grenades and his Kukri knife. In Tunisia, at the Battle of Enfidaville, a team charged a Nazi machine gun. With just their Kukri knives , they won the fight.

Gurkhas served in the Falklands War, where they proved an invaluable tool for psychological operations. Argentine propaganda had been broadcast about the “headhunting mercenaries” being sent to the Falklands by the British. Unfortunately, the Argentine conscripts believed their own propaganda. The British found that if they let the Argentines see them sharpening their kukris, the conscripts would often surrender rather than face kukri-wielding Gurkhas. The kukri is, of course, the traditional Gurkha edged utility and combat blade. Its distinctly curved blade allows it to be swung with great force. It is capable of decapitating a sacrificial animal or a man. Myths abound about the kukri. Including that if the Gurkha draws his kukri, it must draw blood before being returned to its sheath. Also a young Gurkha does not feel he a soldier until he has made a kill with his kukri.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

4. They Are Fearless In Taking Care of Their Own.

Remember, this is the force that would rather die than be thought a coward. As if it wasn’t hard enough to kill a Gurkha. To finish one off, you have to fight through all the Gurkhas protecting their own wounded. They’ll do the same to retrieve a fallen comrade — and they will go through hell to do it.

When two of Capt. Rambahadur Limbu’s men were shot in Borneo by an enemy assault, Limbu fought the enemy back to their starting position with just a handful of grenades. He then ran back to his men to alert them to the enemy’s position. Then he ran back through a hail of machine gun fire to retrieve a wounded soldier. Then he ran back to retrieve the other one, who was killed in the initial attack.

5. They Don’t Care What Weapons You Have.

Did you notice a common thread in all these stories? Gurkhas can be outnumbered, out-gunned or bring a knife to a gunfight and there’s still a good chance they’ll come out on top. They charge machine gun nests, bunkers, tanks and anything else that stands between them and Gurkha glory.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

If you come at the kings, you best not miss.