In an era when the average man had one shot from a fowler or musket, maybe two with a swivel barrel, and the same for a holster pistol, a smoothbore double gun was one of the most versatile weapons of its time. With a double-barreled flintlock, one could deliver two rounds of shot in rapid succession to bring down game birds, hasten the departure of small unwanted predators or, when loaded with round ball, kill larger prey or defend against an armed assailant. It was shotgun and slug gun, offering twice the power of a single-barreled flintlock.

The flintlock as we know it today evolved from a more primitive mechanism known as a “snaphance” or “snap lock” developed in Europe, principally in Germany, Italy, England, France, Scotland and Spain, during the mid to late 1500s. Flintlocks first began to appear between 1595 and 1620 using an improved firing mechanism with a steel surface for the flint, in the jaws of the cock, to strike against.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The flintlock mechanism was more efficient, less complicated to manufacture, more robust and easier to operate than any of its predecessors. The flintlock design used a new L-shaped frizzen hinged at its toe and closed (pushed rearward) to cover the priming charge in the pan. With the hammer fully cocked (it was usually placed in the half-cock position for safety), pulling the trigger released the sear, allowing the hammer to fall and strike the backside of the pan cover, or leaf, driving it forward to expose the priming charge while the flint scraped against the steel surface, creating sparks to ignite the priming powder.

Flash In the Pan

If everything worked, the burning priming powder was drawn into the touch hole, igniting the powder charge in the barrel. When it didn’t work, it was called a “flash in the pan,” an unkind metaphor used today for a short-lived success, but in the 1700s, at the very best it meant a missed shot at dinner. A double-barreled flintlock gave you a second chance, however.

Traditionally styled 18th century flintlock muskets and pistols built during the Revolutionary War era were slowly being replaced with newer and more artistically designed longrifles and fowlers by the end of the 1700s. The necessities of war were no longer the driving force behind arms-makers, but rather fulfilling the needs of Americans as they began to explore and settle territory farther to the west in the early 19th century.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

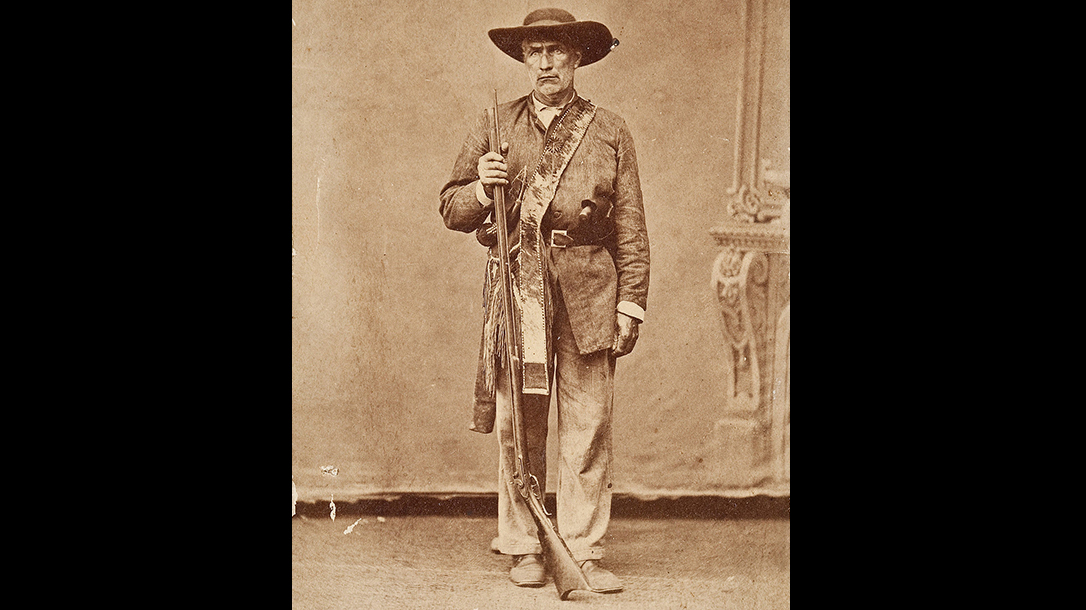

By the 1820s, there were only 24 states in the Union and “the frontier” meant anything west of Missouri. The greater part of the country was “unorganized territory” in the northern regions, the Oregon Country, bordering with Canada, and New Spain, formerly part of Mexico, which encompassed the entire Southwest from the Arkansas Territory to the Pacific Ocean. There was a lot for pioneering Americans to explore and settle. Longrifles, fowlers and pistols were as essential to that effort as a horse and wagon.

Justice In Texas

America’s artisan gun-makers had established various schools of design from the East Coast to the southern states; they were also crafting long arms and pistols of both remarkable quality and elegant appearance. They were, perhaps, the most beautiful rifles and pistols ever produced in America. Flintlocks in the hands of explorers venturing west in the early 1800s were the first arms of the American frontier.

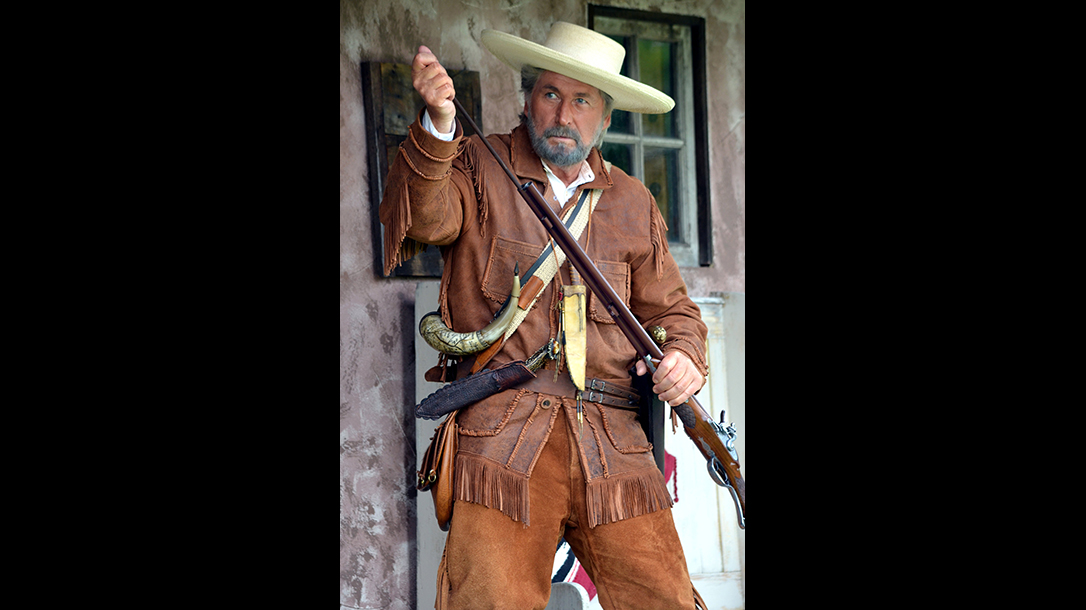

Shotguns—flintlock shotguns to be specific—played a role in the rise of the Texas Republic long before Samuel Colt’s Paterson revolvers were used to rewrite the battle tactics of Texas Rangers in the 1840s. William Travis, commander of the troops sent in support of the Alamo in January of 1836, favored a double-barreled shotgun, and advocated arming the Texas Army Cavalry with such weapons. This was also true as far back as the founding of the Texas Rangers in 1823 by Moses Morrison and Stephen F. Austin. Their duty was clearly set forth by Austin: to protect settlers and their property from Indian raids, cattle and horse thieves crossing the Mexican border, and from the lawlessness that men on the frontier so often brought upon themselves.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The double-barreled flintlock shotgun was no stranger to those the Texas Rangers pursued in the early 1800s. Even after the adoption of Colt’s Paterson No. 5 holster model revolver (better known as the Texas Paterson) in 1844, as well as earlier Paterson pistols, revolving rifles and shotguns purchased by the Republic of Texas in the late 1830s, Rangers in the field (far enough away that percussion caps could be difficult to acquire) still found double-barreled flintlock shotguns to be indispensable tools. All one needed was powder and ball.

Pedersoli’s Take

Davide Pedersoli has been at the center of manufacturing classic European and American flintlock and percussion rifles and pistols for 60 years, but the development of a double-barreled flintlock shotgun is rather new for this legendary Italian arms-maker.

I sat down with Pierangelo Pedersoli at the 2009 SHOT Show, and we began a discussion about European Howdah pistols that dated back to the flintlock and percussion era. At the time, Pedersoli was looking for ways to expand its product line, which already included some of the most famous European and American single-shot long arms and pistols in history. My suggestion of a 19th century European double-barreled Howdah pistol intrigued Pierangelo; over the next couple of years we discussed such designs. Building a left-side pistol lock was the hardest part, even though the company already had the Kodiak Express double rifle. Pierangelo made some prototypes, and in 2011 the first examples of the Pedersoli Howdah were introduced in 20-gauge and .50-caliber versions.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

A couple of years later, we discussed the next step (actually a step back): making a double-barreled flintlock Howdah pistol. Again, the left-side lock was going to be the most difficult part of the design. In the interim, our discussions led to the .45/.410 Howdah (based on the 1920s Ithaca Auto & Burglar models) that was introduced two years ago. This still left our “pet project” flintlock Howdah to be addressed.

60th Anniversary

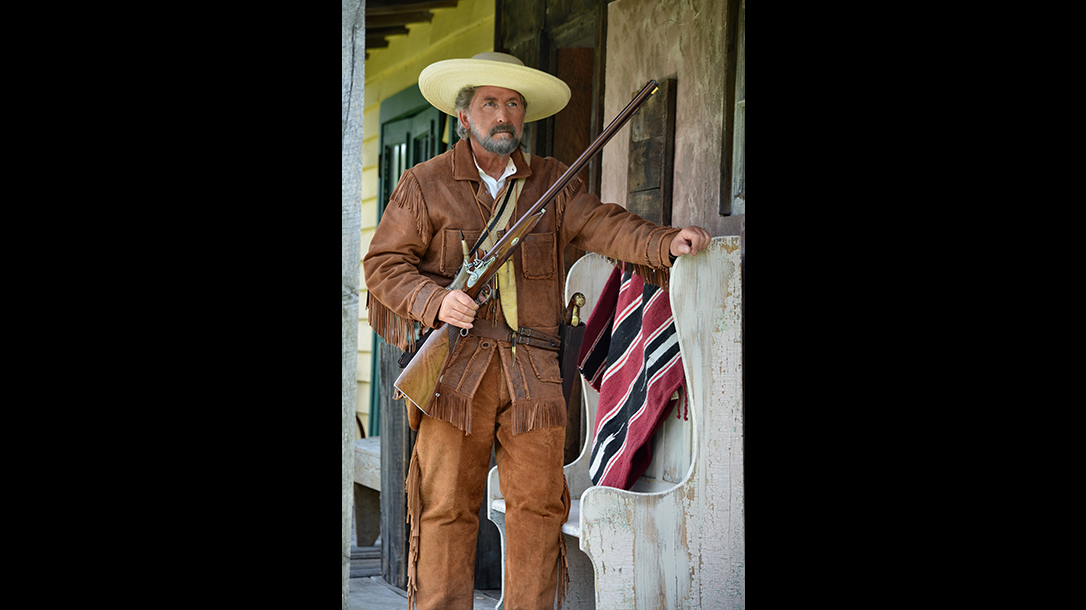

Pierangelo took the most pragmatic approach and developed Davide Pedersoli’s first double-barreled flintlock shotgun just in time for the company to celebrate its 60th anniversary. This classic, French-inspired, 20-gauge double gun is stocked in select oil-finished American walnut with deep checkering on the wrist and forend. The browned, 28-inch barrels are chrome lined and given modified chokes. With an overall length of 44-5/16 inches, the Pedersoli Classic Side-By-Side Deluxe isn’t as hefty as a 12-gauge double gun; it weighs only 7.05 pounds unloaded. It has good balance, classic styling and impeccable handling—all the traits of a late 18th century double-barreled flintlock.

Downrange Action

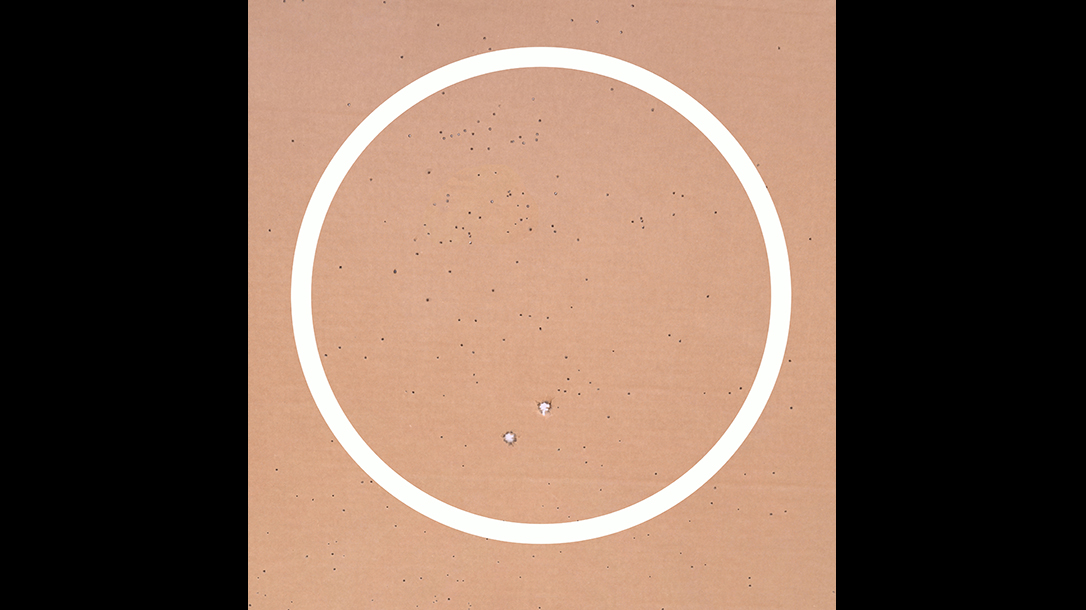

For the first field test of the new Pedersoli Classic Side-By-Side Deluxe, I went with the factory-recommended loads for birdshot and slugs. For game birds, the general load is 1 ounce of No. 7 shot (approximately 70 pellets of 0.1-inch lead shot per ounce) over 60 to 80 grains of FFg. For modern use, this is loaded down the barrel in the order of a shotshell: powder, over-powder card, cushion wad, shot and over-shot card. I went with 65 grains of FFg (FFFg for priming the pan), and my pattern for both barrels at 50 feet left 113 No. 7 shot pellets (out of 144) within an 18-inch circle.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As a slug gun, a job for which this double gun is superbly suited, the barrels were loaded with 70 grains of FFg and a 0.614-inch cast round ball with a lubed patch. Firing two shots at 25 yards produced a cluster 1.75 inches wide just above the point of aim. There were several flashes in the pan and a couple of misfires because the right hammer flint became loose. Both issues with priming the pan and retightening the flint were quick fixes, however; the Pedersoli delivered in terms of accuracy at the two test distances. With practice and working up specific loads for this gun, it would easily be a solid blackpowder hunting gun. And in its day, that was mostly the intended mission of a double-barreled flintlock.

Doubling Down

Pedersoli’s first double-barreled flintlock shotgun is a handsome-looking piece based on styles seen toward the end of 1700s, but not on any one specific model. The distinctive checkering on the stock, however, is inspired by a French shotgun from the same period. And while the components are made using the latest manufacturing techniques, the barrel and stock are finished by hand before final assembly.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

My test sample had a great fit and finish. The wood-to-metal fit was flawless; the lockwork, side plates, tang, triggerguard and tail pipe were all finely engraved to give the flintlock a look commensurate with its price and classic heritage. The Pedersoli Classic Side-By-Side is currently available stateside thanks to the Italian Firearms Group (IFG) in Amarillo, Texas. The MSRP is $1,700.

Pedersoli Classic Side-by-Side Deluxe Specs

| Gauge: 20 |

| Barrel: 28 inches |

| OA Length: 44-5/16 inches |

| Weight: 7.05 pounds (empty) |

| Stock: American Walnut |

| Sights: Bead front |

| Action: Flintlock |

| Finish: Browned |

| Capacity: 2 |

| MSRP: $1,700 |

For more information, visit ifg-usa.com.

This article was originally published in “Guns of the Old West” Fall 2018. To order a copy and subscribe, please visit outdoorgroupstore.com.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below