By Andrew Branca

Proportionality, the third principle of the law of self-defense, is often the one for which most of us who carry concealed firearms tend to be least prepared. Although the principle of proportionality can appear simple on its face—defensive force may not be excessive, meaning that the amount of force used in defense must be proportional to the force threatened—in actual practice it too easily ensnares the armed citizen, even the most well-intentioned and tactically proficient.

The consequences of violating the principle of proportionality are absolutely devastating to a claim of self-defense. Indeed, courts frequently refuse to allow the words “self-defense” to be spoken in front of the jury at all if it deems the defender’s use of force was excessive.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Duration & Intensity

In determining whether a defensive use of force violates the principle of proportionality the courts look to two parameters: duration and intensity.

Excessive duration of force refers to whether the defensive force stopped at the point that the threatened force was neutralized, or continued beyond that point. Any use of defensive force may well be lawfully justified so long as the threat remains. Once that threat has resolved, however, any continued use of force cannot be justified as self-defense, and can be deemed criminal conduct.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

RELATED STORY: Self-Defense Realities – Justified vs. Excessive Force

To put it another way, the first couple of shots you fired may be deemed necessary to resolving the deadly threat you faced, and therefore lawful, but a third shot fired might be deemed to have no lawful justification. In that case it would not constitute self-defense and would subject you to prosecution.

Fortunately, in most cases a misjudgment of a split-second is not enough to be deemed to have violated proportionality. After all, the Supreme Court long ago recognized that “detached reflection cannot be demanded in the presence of an uplifted knife.” Brown v. United States, 256 U.S. 335 (1921). In most cases the time lapse between the end of the threat and the continued use of force must be considerable in order to qualify as excessive.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

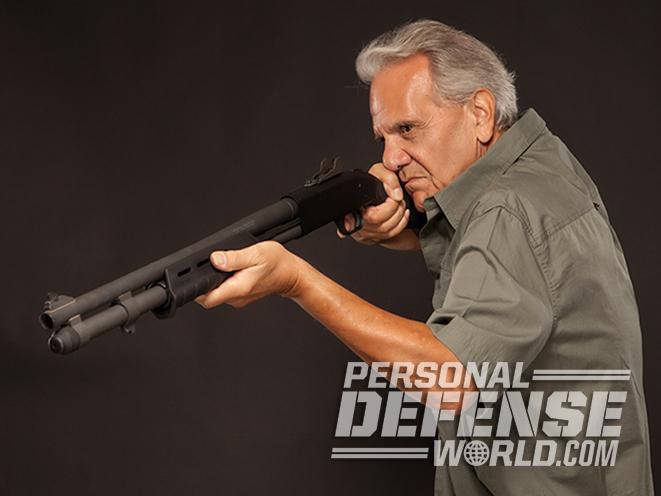

A recent example of excessive duration of defensive force involved an Oklahoma pharmacist who found himself faced with two armed robbers in his place of work. The pharmacist swiftly pulled his own handgun and shot one of the robbers, then chased the second robber away. Up to that point the pharmacist’s use of force was well within the law of self-defense. Unfortunately, he didn’t stop there.

Returning to his pharmacy, he was observed on security footage retrieving a second gun, standing over the fallen robber and shooting him five more times. Although he argued at trial that he believed the robber was still a threat, the jury discounted this narrative of innocence and convicted him of murder in the first-degree. His sentence: life in prison. He recently lost an appeal of his conviction.

Intensity Of Force

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Whether a use of defensive force was excessive in intensity depends on whether the attacking and defensive forces used were non-deadly or deadly in nature. Deadly force is force that involves a substantial risk of death or grave bodily harm. Grave bodily harm includes serious injuries resulting in a loss of bodily function, lesser injuries that result in permanent damage and many kinds of sexual assault. Non-deadly force, in turn, is essentially any force that falls below the level of deadly force.

In general, deadly force in self-defense may only be used to counter a deadly-force threat—that is, an imminent threat of death or grave bodily harm. If the threatened force cannot reasonably be expected to cause death or grave bodily harm, then deadly force may not be used to counter that threat.

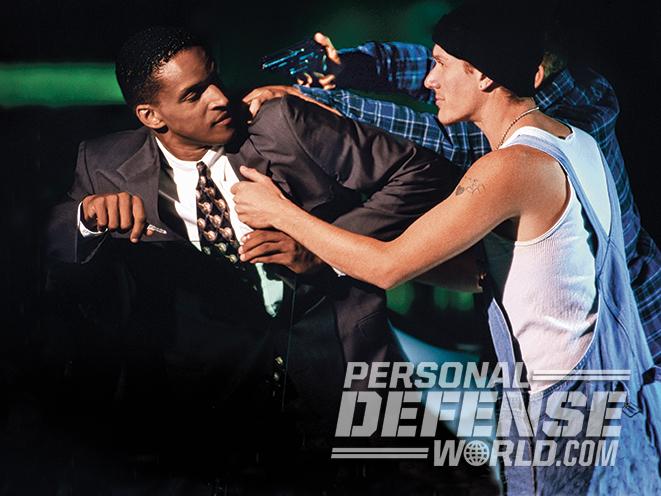

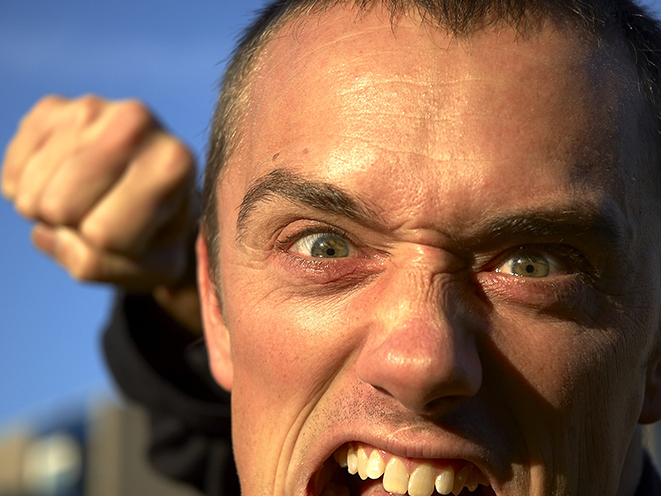

A case from this past summer illustrates this point. The defendant and another man both had a romantic interest in the same woman. At a party where all were present an argument broke out and the other man began to punch the defendant. At some point the defendant drew his gun, the men struggled over the gun, it discharged and the other man was hit. Although the court acknowledged that the other man had initiated the physical conflict, his non-deadly attack provided no justification for the man’s deadly-force defense. He was convicted of aggravated assault with a firearm and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

RELATED STORY: Massad Ayoob – 6 Must-Know Court Cases For Gun Owners

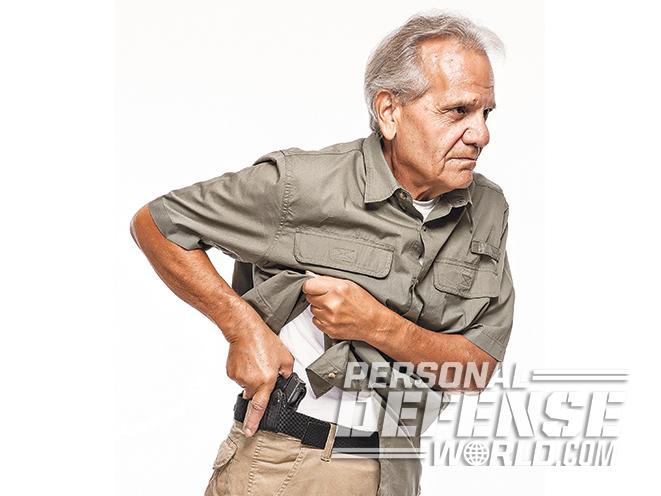

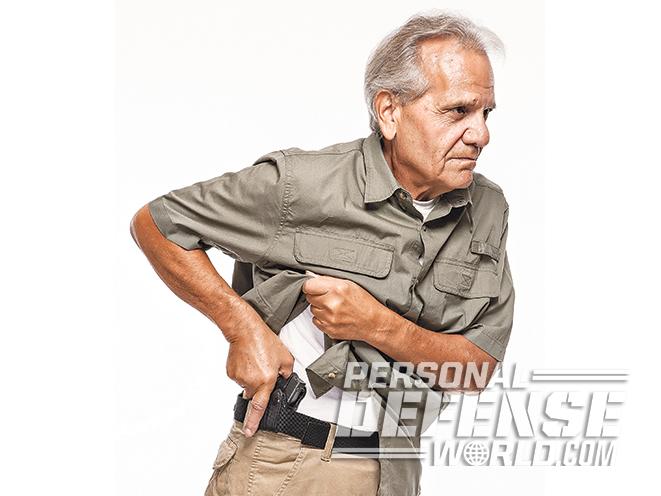

It’s been my observation as a firearms instructor as well as a lawyer that too many law-abiding folks who carry concealed leave themselves vulnerable to this axiom of the law of self-defense. The reason? While they carry a gun, and take reasonable steps to maintain proficiency with that weapon, they have virtually no effective means of non-deadly defensive force at their disposal.

According to the Department of Justice crime statistics, we are five times more likely to be faced with a non-deadly attack than with a deadly-force attack. Yet that handgun we’ve so carefully trained with cannot lawfully be used against a non-deadly attack.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

We’re all familiar with the saying, “If your only tool is a hammer, every problem begins to look like a nail.” But use a deadly-force “hammer” against a non-deadly-force attack and that defensive force simply does not quality as self-defense, as a matter of law. I’ve always urged my clients that anyone who carries a deadly weapon for personal protection is foolish if they are not at least equally prepared to counter a non-deadly attack with an effective non-deadly defense.

There are a limited set of circumstances in which some states allow for the use deadly force in self-defense even when the attacking force may not be, or even definitely is not, deadly in nature.

Many states have established presumptions of reasonableness, in which a legal presumption is created that your use of deadly defensive force was reasonable. Usually these presumptions involve defending yourself in your home, place of business or vehicle. Importantly, however, these legal presumptions can be rebutted by the prosecution by a preponderance of the evidence—and it’s not at all unusual that such presumptions are in fact overcome.

One such case where the presumption was overcome involved a census worker who allegedly stepped into the dwelling of an uncooperative Ohio homeowner. Relying on Ohio’s presumption of reasonable fear statute involving intruders, the homeowner struck the census worker with a bat, after which both parties called the police. Although the court agreed that the census worker may well have been an “intruder” for the purposes of the presumption of reasonable fear statute, they nevertheless concluded that the use of the bat to cause serious injury was disproportionate to any threat the census worker may have presented. The presumption was therefore overcome, and the homeowner was convicted of felony assault with a deadly weapon and sentenced to four years imprisonment.

RELATED STORY: Hands-On Defense – Lifesaving Self Defense Basics

Another case out of Michigan involved a woman who was allegedly taking financial advantage of an elderly man suffering from dementia. The man’s adult son came to his father’s house and lawfully ordered the woman to leave. She refused to leave and attacked him with a metal rod. He defended himself from this attack and compelled the woman off the property. More specifically the man—a former boxer—punched the woman 10 to 20 times, resulting in two days of hospitalization, stitches and other injuries. He conceded that he could have used a lesser degree of force to remove her from the property, but he believed the law permitted him to use whatever force he chose to employ in self-defense against an unlawful intruder.

The trial court disagreed. Although the court acknowledged that the woman was likely stealing from the father, that she had initiated the physical conflict and that the son was entitled to a presumption of reasonable fear of deadly force from an unlawful intruder, the court nevertheless ruled that he had options other than the degree of force he used. The court ruled that his use of force had been excessive, eliminating his right to justify that force as self-defense. He was convicted of a variety of aggravated assault charges and sentenced to 15 years imprisonment.

Colorado takes a different approach entirely with its famous “Make My Day” law. That statute, C.R.S. 18-1-704.5, in some circumstances allows for the use of deadly force against the intruder of a dwelling if the defender reasonably believes that the intruder “might use force, no matter how slight” against an occupant. There, the defender need not worry that the prosecution might be able to overcome a legal presumption of reasonable fear of deadly force.

Texas takes things a step further. Statute 9.42, “Use of force in crime prevention” allows the use of deadly force in some circumstances where there is no offensive threat to any person whatever, but simply to defend personal property. This privilege applies in instances of burglary, robbery or theft during the nighttime when either the property could not reasonably be recovered by any other means or the use of non-deadly force would have necessarily exposed the defender of the property to a substantial risk of deadly force.

Disproportionate Force

As previously mentioned, in a majority of states the use of disproportionate defensive force will strip you entirely of the right to justify that use of force as self-defense. Indeed, if the prosecution can make a compelling pre-trial argument that the defensive force was excessive as a matter of law, the trial judge may very well prohibit the jury from ever hearing the words “self-defense” at trial.

Some states, however, recognize a doctrine known as “imperfect self-defense.” In those jurisdictions, the use of disproportionate defensive force still results in the loss of the traditional self-defense—that is, an acquittal cannot be expected. If that use of disproportionate force was genuinely (but unreasonably) believed to be necessary, and you would have been convicted of murder, the verdict is reduced to “mere” manslaughter. In most states that means that instead of facing a sentence of life imprisonment you’ll be looking at 20 years. Great deal, eh?

The laws governing the proportionality of defensive force, and the varied and complex exceptions to that principle, result in a legal terrain that can be treacherous for the lawfully armed citizen. It is imperative that we understand how these laws apply in our own jurisdictions and those we’ll visit.

Note: Attorney Andrew F. Branca specializes in use-of-force law and is the author of The Law of Self Defense, 2nd Edition. To learn more, visit lawofselfdefense.com.