It began with a patent, an unbreakable patent belonging to Samuel Colt since 1835 that kept E. Remington & Sons at arm’s length from the late 1840s until the day Colt’s seven-year patent extension expired in 1857.

As an American arms manufacturer, Remington was much older than Colt, founded in 1816 by Eliphalet Remington II. Originally, Remington only manufactured barrels but did so quite successfully. In 1828, the company moved from Litchfield to larger facilities in Ilion, New York, along the Erie Canal, a major trade route in the 19th century. While Samuel Colt was busy rebuilding his fortunes in 1847 with the .44-caliber Walker and Whitneyville Dragoons, Remington was busy purchasing the Ames Company of Chicopee, Massachusetts, in 1848. He used Ames tooling to manufacture his first complete gun, a breech-loading percussion carbine built under contract to the U.S.

Navy. It was followed by a contract for 5,000 U.S. Model 1841 percussion “Mississippi” rifles. As for manufacturing revolvers, Remington (and every other U.S. arms-maker) was effectively blocked by the Colt patent. Nearly a decade would pass before Remington introduced its first model, the Remington-Beals revolver.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

It was designed by Fordyce Beals, who shared not only the name but the June 24, 1856, and May 26, 1857, patents. Introduced on the heels of Colt’s patent expiration in 1857, the relationship with E. Remington & Sons and Fordyce Beals would continue for years, leading to many of the company’s most successful models.

Roaring Big Guns

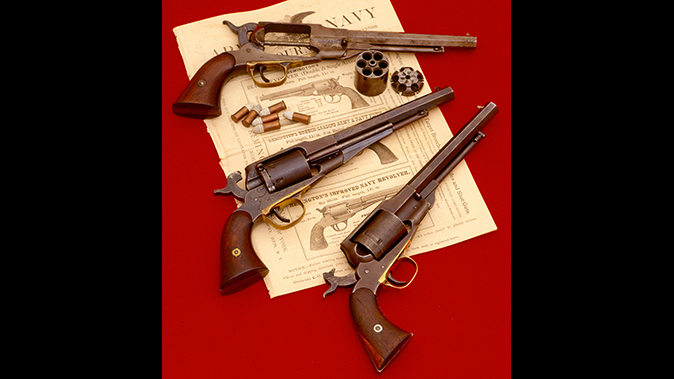

In 1858, Remington and Beals raised the bar for .44-caliber handgun designs with the introduction of the Remington-Beals Army model, an immediate and successful rival to the Colt Dragoons and their comparatively outdated (in Beals’ opinion) construction. The .44-caliber Remington Army was followed by a .36-caliber Navy Model.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Over the years, Samuel Colt had continued to rely upon his original patent designs using a separate frame and barrel, which were joined with the cylinder on the arbor and secured in place with a wedge passing through the barrel lug and arbor. This was the traditional open-top design that everyone in the U.S. was trying (unsuccessfully) to copy and produce. Colt brought swift litigation against all copies. Beals and Remington were not interested in copying Colt, but rather building a different type of revolver that would, by design, be stronger and use a one-piece frame with a topstrap. And it would be far easier to reload.

One had two options when reloading a Colt: Pour a measure of powder into each cylinder chamber, load a lead ball, turn the gun over and place a percussion cap on the nipple of each chamber. The second method was to disassemble the gun by removing the barrel and swapping out the empty cylinder for a loaded one. This was faster so long as you didn’t lose the barrel wedge.

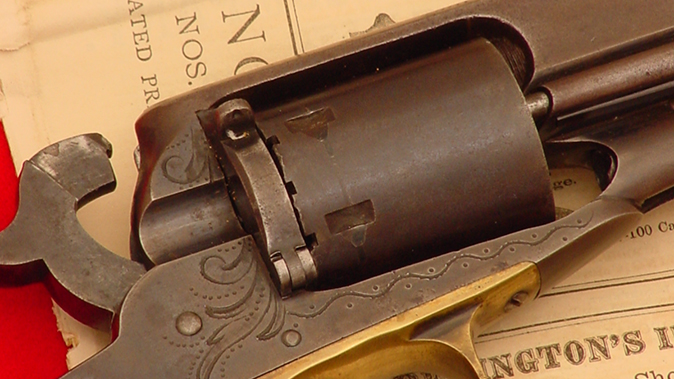

With the Remington and Beals revolver design, traditional loading was the same as the Colt, but a cylinder change took only seconds and required virtually no disassembly. One placed the hammer at half-cock, lowered the loading lever and pulled the cylinder pin forward, rolled the empty cylinder out of the frame, put in a loaded one, pushed the cylinder pin back into place and then raised the loading lever. (You may recall seeing Clint Eastwood do this in the middle of a gunfight in Pale Rider and Anson Mount in the AMC television series Hell on Wheels.) It really was a better idea.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

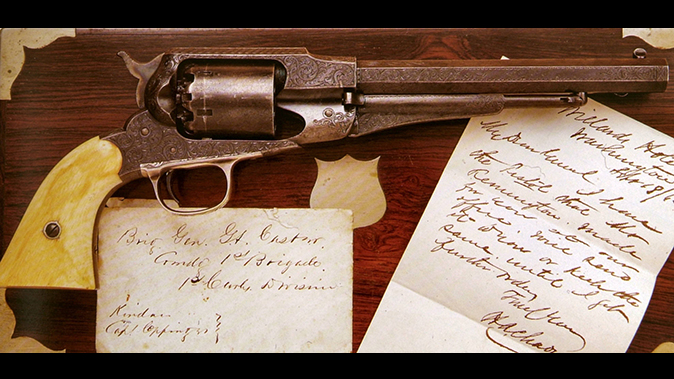

With the start of the Civil War, Remington did not rest on its laurels. The Army and Navy models were fast becoming the Union’s second most carried sidearms. During the course of the war, Remington continued to make improvements to its original .36- and .44-caliber models, introducing the improved Army in 1861 and New Model Army and Navy in 1863. By the end of the Civil War, Remington had produced the second largest quantity of handguns used by the Union, a total of nearly 130,000 revolvers, of which more than 115,000 were .44-caliber models. Remington was also the benefactor of Colt’s misfortune—the factory fire of February 4, 1864—which destroyed the original structures erected by Samuel Colt in 1855. The fire destroyed the buildings where revolvers were manufactured and finished. So, the 1864 fire certainly played a role in the Ordnance Department’s increased orders from Remington before the end of the Civil War.

While Remington touted its superior designs, the Army and Navy models were not perfect. Remington’s revolvers were more prone to jamming than Colts and required more meticulous care. But there was much to be said for the ease of reloading, especially in the midst of a battle.

The Second Blockade

Remington had the misfortune of weathering one unbreakable patent to end up facing another by the end of the Civil War. This time even Colt was being held at bay—both companies were prevented from manufacturing breech-loading cartridge revolvers by Smith & Wesson and the Rollin White patent, which S&W had wisely purchased in 1855. With the White patent, Smith & Wesson had blocked any advances in American handgun design for a decade with the exclusive rights to manufacture breech-loading revolvers in the U.S. until 1869. And like Colt before them, S&W pursued litigation against all violations.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

This had proven unfortunate during the war, as metallic cartridges and cartridge-loading handguns were becoming the most advanced form of personal armament. With self-contained metallic cartridges, it was possible to reload more quickly and shoot with greater reliability. Thus, Remington bit the bullet, so to speak, and in 1868 and 1869 paid a hefty $1 royalty to S&W for every cartridge conversion revolver they built. They also agreed to stamp the Rollin White patent dates on each cylinder. Colt would have none of it, and for the first time since 1857, Remington had the edge over its biggest competitor in the handgun market-place.

Remington signed the agreement with S&W in February of 1868 and a total of 4,574 Remington New Model Army percussion models were converted to fire .46-caliber rimfire metallic cartridges. The majority of the guns were actually sold by S&W to Benjamin Kittredge, a wholesale and retail firearms dealer in Cincinnati, Ohio, who had initiated the request for the cartridge conversion models through S&W a year earlier. During this period S&W was only building .22 and .32 caliber breech-loading pocket pistols, and would not introduce a large-caliber model until 1870.

The Remington conversions required the manufacture of a new cylinder since the .46-caliber rounds wound not fit within the diameter of the original six-shot .44 percussion cylinder, thereby ruling out the possibility of cutting off the back and boring the chambers through. The .46-caliber Remington conversions only chambered five rounds, but they were five big ones.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The back of the frame, where the cylinder butted up against the recoil shield, was dovetailed to accept a new recoil plate, which was fastened with a small screw. The right side of the recoil shield and frame were deeply channeled to allow the loading and extracting of cartridges; however, there was no loading gate, and the majority of early .46-caliber conversions were not fitted with cartridge ejectors.

The same basic design was used for later models chambered to the new .44-caliber Martin centerfire and Colt .45- caliber centerfire cartridges. These later designs, introduced in the summer of 1869, were six-shot revolvers and offered a manual cartridge ejector assembly mounted on the left side of the frame.

Remington’s New Model Navy was the next percussion revolver to get the conversion treatment beginning in 1873, chambered for either .38 rimfire or .38 centerfire cartridges. The Navy was also the first model to come standard with both a loading gate and cartridge ejector.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Just as Colt was doing in the early 1870s, Remington produced both new conversions to use up Civil-War-era percussion frames and barrels, as well as modifying older percussion models sent to the factory by the military or civilian owners. In 1875, the U.S. Navy contracted to have 1,000 Navy percussion revolvers used during the Civil War returned to Remington for conversion to .38 centerfire. The cost of converting the Navy models was $4.25 each, including new grips and refinishing.

Following the war, Remington also introduced several new percussion models, among them the New Police revolver and New Pocket revolver in .36 and .31 caliber, respectively. Along with the Remington Rider, all of the new pistols were available with factory cartridge conversions.

The New Police was chambered for the .38 rimfire while the New Pocket revolvers (designed by Fordyce Beals) was in .32 rimfire. Unlike the earlier Remington cartridge designs, both could easily be converted back to percussion pistols by changing cylinders, thus providing greater versatility than Colt models, which, once converted, could not be used with a percussion cylinder.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Two-Part Solution

Remington’s new approach to the conversion of its percussion revolvers was considerably more diverse than Colt, which had taken only one course of action with the C.B. Richards and William Mason designs. Remington’s new conversions utilized several different methods, one of which followed three influential British designs—the C. C. Tevis patent (1856), the J. Adams patent (1861) and the W. Tranter patent (1865)—all of which made use of a two-piece cylinder. This required cutting off the back portion of the cylinder below the percussion nipples, drilling the chambers completely through and counter-boring the back of the cylinder to accommodate the cartridge rims. A cylinder cap, with ratchets to engage the hand and openings to allow the hammer to strike the cartridge rim, completed the conversion.

Fortunately, the design of the Remington hammer required only slight modification in order to work with the two-piece cylinders, and it would still work with the percussion cylinder. By simply replacing the old cylinder, the gun could be used as a conventional cap-and-ball revolver, which proved fairly handy on the frontier where a box of cartridges couldn’t always be found.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

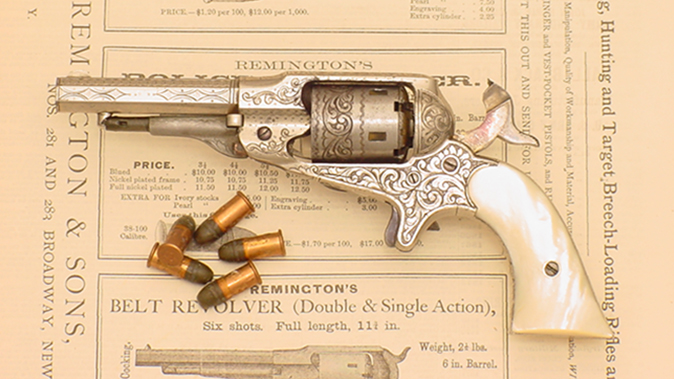

Approximately 18,000 New Model Police Remington revolvers were built between 1865 and 1873, with many of them converted to metallic cartridges. Remington offered the Police model with a choice of four barrel lengths: 3½, 4½, 5½ and 6½ inches. Prices ranged from $10 to $11, and options included a nickel-plated frame for an extra $0.75 and a full nickel finish for $1.50. Ivory stocks were $5 extra; pearl, a whopping $9, and engraving added another $5. A fancy New Model Police with a 6½-inch barrel would have set its owner back a total of $26.50 in 1873. A box of 100 .38-caliber rimfire cartridges cost $1.70, and a case of 1,000 rounds was $17.

The same conversion principle used for the New Police applied to the smaller, five-shot New Pocket model, which become one of the most prolific of all cartridge conversions. The Pocket Remington revolvers had been manufactured as percussion revolvers from 1865 to 1873. Thus, there was nearly a decade of production before the conversion to .32 rimfire was introduced in 1873. The pistols were available with 3-, 3½-, 4-and 4½-inch barrels, though the latter two lengths were actually quite rare. More than 25,000 Pocket models were produced, with the majority either converted to or produced as .32-caliber cartridge pistols. The Remington revolvers were available with both cylinders, again making the Remington a more versatile model than a comparable Colt pocket pistol.

Among the rarest of Remington conversions are the Belt Model Remington revolvers, which were smaller than the New Model Army and Navy but larger than the .38-caliber New Police, and carried six rounds. It is estimated that no more than 3,000 Belt Models were produced and only a fraction of those were converted from .36-caliber percussion to .38-caliber rimfire. Even rarer is the Remington-Rider Double Action New Model Belt Revolver, which was identical in all respects to the single action except for the trigger mechanism. Both SA and DA models utilized six-shot, two-piece cylinders and 6½-inch octagonal barrels.

The .36-caliber Remington Navy was also an excellent candidate for conversion, having the same basic design as the .44-caliber Army. The earliest designs were based on the Remington-Beals Navy models, but the majority of conversions were performed on the New Model Navy revolvers circa 1863 to 1878. The Navy models were fitted with hinged and latched loading gates, and nearly all came with ejector assemblies. The factory conversions sold for $9 and were chambered for .38 rimfire cartridges. Later models (circa 1874) were available in .38-caliber centerfire.

End of Remington Revolvers

By 1875, Remington had converted or built thousands of cartridge revolvers in a variety of calibers and models. The New Model Army conversion went out of production in 1875 with the debut of Remington’s first all-new large-caliber cartridge model, the 1875 Single Action Army. The .38-caliber 1863 New Model Navy conversion, however, remained in production for another three years, and conversions of the New Model Police were done as late as 1888. The Belt Model was discontinued in 1873, as were the Remington-Rider Double Action versions. For E. Remington & Sons, the era of the cartridge conversion was nearing an end.

E. Remington & Sons, which was headed in later years by Eliphalet Remington’s eldest son, Philo, prospered well into the post-Civil War era and during America’s Western Expansion but suffered a severe reversal of fortune in the late 1880s and was forced into receivership in 1886. The company was reorganized two years later as the Remington Arms Company under the control of Marcellus Hartley and the New York sporting goods firm of Hartley & Graham (previously Schuyler, Hartley & Graham), which had played a significant role during the Civil War supplying the Union with arms and ammunition. Remington later merged with Hartley & Graham and the Union Metallic Cartridge Company (founded by Hartley after the Civil War), becoming Remington-UMC in 1912. Today, the Remington Arms Co. still operates out of Ilion, N.Y.