Wounded, grasping the side of a Kiowa helicopter’s rocket pod and shooting her M4 Carbine to suppress Taliban fighting positions, rescue pilot MJ Hegar (Mary Jennings) was hardly orthodox, but neither was her career in the United States military.

Traditional combat heroism narratives are cleanly packaged with predictable moral challenges and emotional or physical prices paid. However, M.J.’s story is atypical and grittier, which makes it more genuine. Most military pilots attend service academies, but she did not. In fact, she was denied entry into flight school four times while in the Air Force.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As a woman in the military, M.J. had to work twice as hard to prove her worth in the boy’s club that is the fraternity of arms. Despite her determined work ethic and willingness to embrace dangerous and adrenaline-fueled challenges, she would learn that although you do everything right and try your hardest, you can still fail. That lesson would resonate throughout her career. It would also be paramount in framing her actions the day she was shot down in combat.

M.J.’s repeated rejection from the Air Force flight school was a combination of a sexist chain of command, a physically abusive husband and missed timing. However, rather than blaming the slow-to-change culture of the military, she learned to navigate around obstacles that would discourage most people.

“Any time I was discriminated against, I was shocked. But I learned I couldn’t walk around with a chip on my shoulder, because that would just validate anything negative that others wanted to think about me,” she said.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

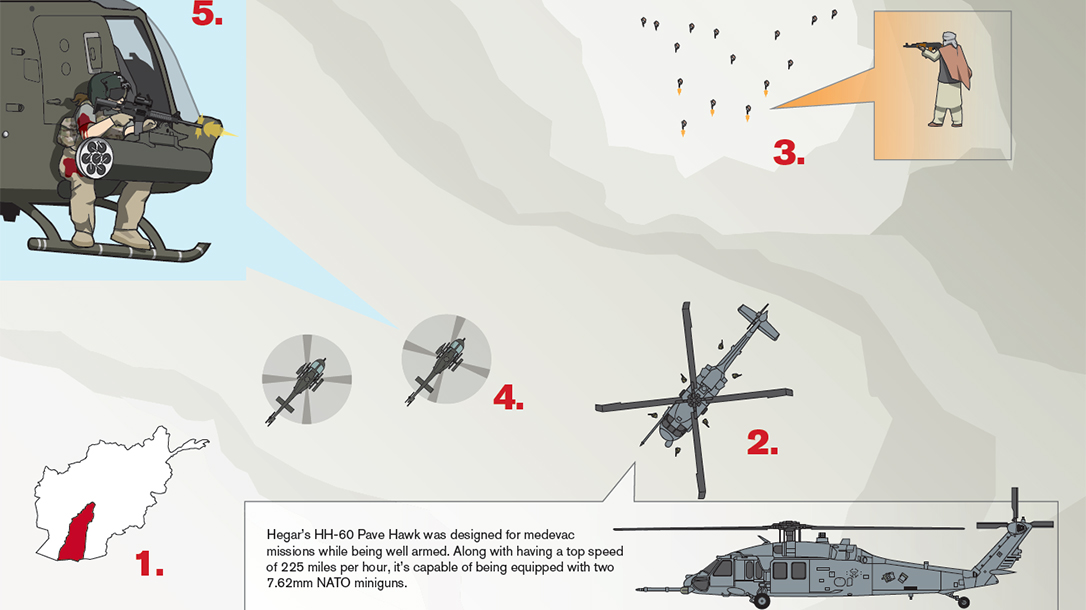

It wasn’t until after leaving active duty from the Air Force that she was able to apply for flight school in the Air National Guard. Electing to fly the Air Force’s HH-60 Pave Hawk (a derivative of the U.S. Army’s Black Hawk), M.J. saw action as a search-and-rescue pilot domestically and overseas in Afghanistan. Spanning three combat deployments and 300 sorties, her crew repeatedly flew into hot landing zones to extract Special Forces operators, foreign commandos and Afghan villagers.

Into The Breach

Of the 300 missions that M.J. flew, about 40 percent were in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province. Unlike the hit-and-run guerrilla-style action more common throughout the country, the Taliban in Helmand possessed the capacity and equipment to execute large-scale conventional attacks. Helmand Taliban forces sometimes numbered in the hundreds. They accomplished something few militaries are capable of: making Western ground forces feel vulnerable.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

From 2006 until 2011, British and American soldiers endured the fiercest fighting of the Afghanistan War in a province that refused to be tamed by coalition forces. In 2007, M.J. and her crew deployed into thick of the fight, flying medevac sorties that rivaled the intensity of missions in the Vietnam War.

“When we got shot at flying in and out of KAF [Kandahar Airfield], it was likely some amateur trying to impress his buddy,” she said. “But when you got shot at flying into Helmand, it was by Taliban that knew what they were doing.”

Something happens after enough trips outside the wire. Soldiers eventually adopt some form of emotional numbing to cope with the realities of combat. For medevac pilots, this experience is twofold. They must acknowledge and embrace that they might be killed. They also experience the often-overlooked heartache of transporting wounded or dying soldiers.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

“When you see a grown man getting loaded onto your bird, and he looks desperate and afraid, or when you can smell the burnt flesh of Americans, or when you can hear the screams of a child … that stays with you,” she said.

The Turning Point

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

M.J.’s trial by fire moment came on her first deployment. She flew into a hot landing zone to extract a Special Forces soldier who was shot in the arm but fighting for his life because the bullet had entered his chest.

“Protocol states that we don’t allow anyone but the wounded on board,” she said. “Otherwise, we start to throw off the weight, and flying might become an issue. But when that Green Beret was loaded onto our bird, his teammate gave my flight engineer a look that clearly indicated that there was no way he was leaving his buddy behind.”

Air Force Pararescue “PJs” began working on the wounded soldier. M.J. heard their traffic over the radio indicating he was code blue. It meant he’d lost his pulse and was minutes from death. Towards the end of the flight, M.J. broke protocol and left her slower sister ship behind to land sooner at the airfield.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

“Seconds were critical, and maybe if we’d gotten back sooner, it would have meant the difference,” she said. “After we lost that Special Forces guy, I shed my naive eagerness to go on missions that ignored the reality that if I was flying, it meant someone else was likely dying. My outlook was more serious from that moment on.”

After losing her first casualty, M.J. exercised the natural self-doubt and re-examination of events all soldiers experience after their baptism by fire. Addressing how she could have shaved off extra minutes, she replayed the mission in her head to identify anything in her performance that might have changed the outcome.

The unfortunate reality of M.J.’s experience—and those of many combat soldiers—is that you can perform your job perfectly but still lose.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Breaking Barriers

Years later, M.J. reflected on losing her first casualty. She uses the experience to provide perspective about narratives of women in combat.

“You know what’s complete bullshit? The argument that says women can’t serve in combat because men won’t be able to handle seeing a woman maimed or killed,” she said. “That’s nonsense. Sorrow is gender neutral. Soldiers have a hard time watching any soldier get wounded. The look on that Special Forces soldier’s face when he got on my bird knowing his buddy was probably going to die—that wasn’t pain that can be qualified as being felt for a man or woman. It was for kin.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

During her missions, M.J. continued to defy arguments that suggested gender was an indicator of a combat soldiers’ inherent abilities. During one rescue, M.J.’s crew flew into a hot landing zone to extract Dutch Special Forces that were getting hammered on the ground. Flying in, door guns blazing, they extracted wounded soldiers but also reinvigorated the ground forces to rally and continue their advance. The Dutch ground force commander later radioed the crewmembers, saying, “You have given my Vikings brave inspirations today.”

For ground forces, language does not exist to describe the emotions experienced upon the arrival of close air support or gun-slinging medevac helicopters. The rush of adrenaline and power stems from the change in your reality, knowing that you’re no longer alone because of the arrival of angels on your shoulder. M.J. and I discussed that sensation, and how it creates a sense of purpose often misrepresented in society.

“People ask me, ‘Are you a warmonger? Why do you like it?’” she said. “And I don’t know if that’s what they think they’re supposed to ask, or if they really mean it, but they’ll never understand. When you’re on mission to rescue Americans, it feels as if your very soul is telling you that this is where you belong.”

Mayday, Mayday

A soldier’s relationship with fear during battle is another dynamic that’s often misrepresented. When interviewed, M.J. is typically asked the predictable and canned question, “Were you scared the day you were shot down?”

Without hesitation, she responds, “No.”

Unfortunately, that typically leads the conversation in a different direction. A direction in which interviewers satisfy their narratives about soldiers and how they cope with fear.

We talked about this for a while and exchanged our beliefs. We agree that it’s not that you’re not scared. Rather, you don’t really have time for that. Your training kicks in, and you start reacting. On the mission where M.J. was shot and shot down, a sequence of events unfolded that continually progressed toward the worst-case scenario. Equipment failures, miscommunication and aggressive enemy fire tested her ability to immediately adapt and lead her crew back to safety.

After their crash landing, M.J.’s crew and wounded patients formed a perimeter and defended their crash site for 20 minutes. Rescue operations wouldn’t begin until a daring Kiowa pilot disobeyed protocol and landed next to the crashed Pave Hawk. Transporting troops wasn’t part of the Kiowa’s design, so M.J. and her crew began hooking onto the sides of the helicopter’s rocket pods with lanyards for a hot exfiltration.

“That’s when I saw muzzle flashes,” she said. “The Taliban left their fortified fighting positions in a gamble to shoot down another bird.”

In a sequence fit for any action movie, the Kiowa helicopter lifted off the ground, with M.J. sending covering fire while barely strapped to the side of a rocket pod. In the mission debriefing, the Kiowa pilot expressed relief that M.J. began shooting to suppress the threat. He couldn’t fire back with the crew strapped to the side of the helicopter. But that didn’t matter, because he had already run out of ammunition.

Awarded for her actions, M.J. received the Distinguished Flying Cross with a “V” for valor device. She is one of 12 women to have ever received the award. Her experience as a soldier challenges the traditional arguments against women in combat, and her actions the day she was shot down demonstrate that leadership on the battlefield is gender neutral. And now you can read about her experiences and more in her book “Shoot Like a Girl.”

“My book isn’t a female leadership book,” she said. “It’s just a leadership book, period. If you don’t fit society’s understanding of a demographic, don’t let other people tell you what to think. Have the courage to pursue what you want, and if you fail, never quit.”

For More Information on MJ Hegar

Visit: MJForTexas.com

This article is from the winter 2018 issue of Ballistic Magazine. Grab your copy at OutdoorGroupStore.com.